Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

That cities will change is indisputable: urban evolution mostly signifies healthy growth, but it is also true that in the contemporary context, gentrifying neighborhood change increasingly operates on an extraterritorial plane, happening quickly, opportunistically and unilaterally. Neighborhoods are evaluated and disposed of as trading commodities in a process that violates the citizen’s fundamental right to the expectation of a stable dwelling situation. Gentrification also threatens a city’s spatial heterogeneity which, through its diverse forms and meanings, can support the enactment of democratic urban life. It leaves little room for a broader discourse around place – a discourse that might lead to the creation of more porous urban space, to the emergence of hybrid institutions and to new sites of pluralistic engagement. This paper will consider a pair of contiguous neighborhoods in Philadelphia where market-driven gentrification has come face to face with powerful grassroots civic advocacy; and it looks at what architects, landscape architects and urban designers can do to help neighborhoods resist gentrification and support heterogeneity in making places where the hand-print of multiple publics might be found.

In cities where de-industrialization has left large segments of their populations in poverty, once stable working class neighborhoods are increasingly threatened by market-driven gentrification. Change happens as if over night, and longtime residents, finding their communities transformed in terms of economic class and race are subject to a rising cost of living and often pressured to move. With their departure, the local culture built up over time is eroded; cleansed of its unique qualities of place, it is replaced with spatial products of the dominant commercial culture. Here gentrification violates not only the citizens’ primary right to the city but poses a threat to the city’s spatial heterogeneity which, in its diverse forms and meanings can support the actualization of democratic urban life.

That cities will change is indisputable: urban evolution mostly signifies healthy growth, but it is also true that in a contemporary context neighborhood change increasingly operates on an extraterritorial plane, happening quickly, opportunistically and unilaterally. With the invisible hand deftly at work, neighborhoods are evaluated and disposed of as trading commodities with “exchange value” rather than as mosaics of places for diverse constituencies. Lost in this singular profit model is the notion held by Lefebvre of the citizen’s right to appropriation including access, use and pleasure that constitute a broader conceptualization of ownership. 1 Gentrification and its tightly defined spatial and programmatic tropes leave little room for a broader discourse around place – a discourse that might lead to the creation of more porous urban space, to the emergence of hybrid institutions and to new sites of pluralistic engagement.

This paper will consider a pair of contiguous neighborhoods in Philadelphia where market-driven gentrification has come face to face with powerful grassroots civic advocacy; and it looks at what architects, landscape architects and urban designers can do to help neighborhoods resist gentrification and support heterogeneity in making places where the hand-print of multiple publics might be found.

WHAT DOES DESIGN HAVE TO DO WITH IT?

The literature of gentrification – theories, processes, and social impacts – resides primarily in the realms of political science, sociology, urban studies and geography, addressing careful place-based studies through the lens of larger cultural and economic drivers. 2 These are serious critical analyses and by nature do not propose resolutions, especially not in material spatial projections that architects employ. But the consequences of gentrification are played out in actual physical space, so it is important that a discussion of the phenomenon that has radically changed neighborhoods worldwide be more fully explored in the literature of architecture and urban design practice.

In the 1960s and ‘70s when the agents of gentrification and displacement were clearly defined public entities empowered by urban renewal policy, architects were active, vocal advocates for change. Then battle lines were clear. Not so in our contemporary neoliberal economic environment where the prime movers in gentrification operate behind the scenes. Private developers, seeking profit in emerging new markets in neglected, strategically located neighborhoods partner quietly with public policy makers. Together these public-private partnerships build tax revenue and national status, marketing the gentrified neighborhoods as a product of the “creative class” and young people are welcomed into “up and coming” neighborhoods. First gradually, then rapidly, the ragged edges are smoothed, rents rise and poorer old-time residents relocate. A far cry from the ethos of creative risk-taking that the hip emerging neighborhoods were meant to represent, a haunting predictability begins to pervade the newly gentrified urban spaces. Cafes, bike shares, dog parks, galleries, and pop-up parks proliferate and are replicated from city to city. 3 (Fig. 1.)

Many architects and designers feel that they are powerless in the face of this economic juggernaut. Among them many who are social advocates often find themselves mirrored in this branded environment and are ambivalent about their complicated relationship with gentrification: they are both its agents and consumers. 4 Yet this very ambivalence could be instructive and valuable. Since architecture and its allied design professions are inevitably entangled with capital and production of space, both sides of the issues surrounding gentrification are present in design practice, and can be used to mitigate its negative social impact. 5 Far from being without agency in this struggle, architects, planners and landscape architects have the skills to closely read patterns of spatial use, to anticipate gentrifying trends, to imagine and co-design community futures to pre-empt gentrification – in essence to help secure the right to the city for its diverse constituents. (Figs. 2a and 2ab.)

Indeed, important social impact design practices tackle project-based work that addresses inequity and a weakened democratic context. 6 While these practices have created a movement that benefits the public interest, most do not explicitly situate the work in the broader political and cultural framework of gentrification. There are notable exceptions: Rios and Aeschbacher – each steeped in community-based practice – have argued that designers “who intervene directly in the world can create physical social spaces for others and in some cases seek to redefine asymmetrical power relationships.” 7 The work of Estudio Teddy Cruz in San Diego border communities and of Alex Salazar in Oakland that both seek a redefinition of the role of design as a means of challenging neoliberal policies around housing, zoning and real estate development. All argue for an expanded political context for design thinking in a world that embraces privatization, deregulation and market bias. While making conceptual links with the macro-environment, practice is locally grounded, at a scale understood in depth by ordinary citizens. With this knowledge powerful place-centered partnerships can be forged and asymmetries can be recalibrated. Teddy Cruz exhorts us to “focus on the issues of the local [because we will find] every issue converges there.” 8

THE GENTRIFICATION DEBATE: CHANGE AND HETEROGENEITY

In the 1960s, as the suburbs began to lose their appeal, a back-to-the-city movement was begun led by those willing to take risks on “dodgy” neighborhoods – the young and well-educated, do-it-yourselfers and artists looking for unique and affordable residential and working space. Seeking escape from banality, to the authenticity, grit and diversity to be found in the city, they were often unaware of the social consequences of their colonization of poor neighborhoods as well as of the invisible mechanisms that increasingly have supported and guided their “pioneering spirit.” 9 Much like the westward expansion in its quest for resource accumulation, the urban pioneers’ blind appropriation of space disregards the underlying human value of what appears wasted and uncultivated. (Fig. 3.)

There is an on-going debate between those who would tout the emancipatory nature of gentrification 10 versus those who condemn the “brutal inequalities and economic fortune that are produced in the process.” 11 The short-term effects of gentrification on so-called quality of life issues are often positive, and longtime residents have expressed mixed feelings about neighborhood change. The study of Harlem for example showed only minimal displacement, and many neighbors appreciated the improved amenities, reduced crime rate, school improvement and increased housing values. 12 But over time costs tend to outweigh the benefits in the form of increased taxes, rents and the influx of expensive retail making local shopping unaffordable. And the immeasurable costs are more subtle and affective. Observers like psychiatrist Mindy Thompson Fullilove have eloquently expressed the damage to the emotional ecosystem done by uprooting people from their homes. 13 Those who can afford to stay often suffer from feeling like a stranger in their own neighborhood where the social capital is found in familial ties and history. 14 And with this the dismantling of cultural patterns and neighborhood ethos come the development of new hip, socially exclusive establishments. 15 In a poignant capitulation to the commodification of the dwelling, residents will often sell out at a considerable profit only to find they cannot afford housing in as good a neighborhood and must again forge new communal bonds.

PARALLEL WORLDS: A CASE STUDY

In this context we examine the emerging transformation of two adjacent neighborhoods in the Kensington area of eastern North Philadelphia. Research and design partnerships with both neighborhoods have been established over several years. Questions of gentrification; shared and differing neighborhood agendas; and overlap and intersections of spatial claim have been explored through meetings and interviews with stakeholders, residents, leaders, and policy makers. In addition, physical spatial analysis and projections have been undertaken through community-based studios in architecture and in a theis project in landscape architecture.

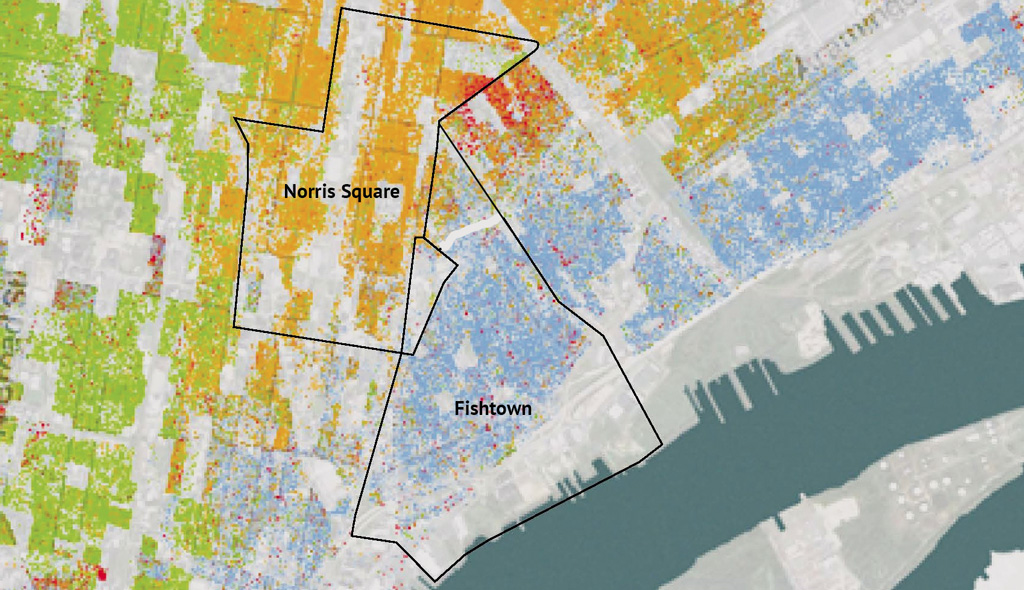

Despite their close proximity, Fishtown and Norris Square have grown as separate parallel worlds, ethnic enclaves with intensely inscribed identities that owe much to different underlying spatial structures and development histories. Fishtown, an historically white working class neighborhood is in the full throttle of gentrification, with artists and other well educated young people moving into what has become Philadelphia hottest “creative” neighborhood. Across a sharp geographic boundary where different street grids collide at a scruffy commercial corridor darkened by the elevated train, is the poor, but well-organized Latino neighborhood of Norris Square. The neighborhood has its own unique spatial and visual identity, built incrementally over several decades. Market pressures spreading to Norris Square are forcing conflict over affordable housing and along the border zone between the two neighborhoods. Here the unequal power relations inherent in gentrification beg the question of social justice as a spatial function. (Figs. 4a and 4b.)

Racial dot map showing the dramatic divide along the Front Street corridor between Norris Square and Fishtown. The long triangular space in between the two neighborhoods was for years a "terrain vague." (Yellow: Latino; Blue: Caucasian; Green: African American). Image © 2013, Weldon, Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (Dustin A. Cable, creator).

The Norris Square neighborhood is a product of Philadelphia’s rapid late nineteenth century century industrialization; after the late twentieth century industry collapse the neighborhood depopulated becoming known as the “Badlands.” Members of Puerto Rican community displaced by the publicly sanctioned gentrification of urban renewal resettled in this “ghetto of last resort” 16 drawn by the large square, a spatial anomaly in the otherwise undifferentiated gridiron layout of central North Philadelphia. The square, surrounded by struggling institutions and vacant brownstones was in the 1970s a famous drug market, but a group of young mothers bent on building the neighborhood into livable place for displaced Latino families, rallied the local Catholic church and police and occupied the park, holding midnight prayer vigils and peace marches, and gradually appropriated the space. 17 The community commands a remarkable identity-building amenity in the park, which is now well tended and a site for relaxation and active recreation, movie nights and community gatherings.

Grounded in grassroots activism the Norris Square Civic Association (NSCA) has acquired and renovated much of the housing surrounding the park for preschools and social services; it has built 150 units of affordable family and senior housing, and it is developing a large community center in a cluster of buildings once occupied by a monastic order. 18 Particularly moving is a gardening initiative has appropriated multiple vacant lots just off the square for urban farming and sites for the expression and celebration of Latino culture. Flower and vegetable gardens, a casita with an outdoor kitchen and a chicken yard, brilliant murals and installations of everyday artifacts form the growing landscape of “Las Parcelas.” (Fig. 5.)

La Parcelas, Norris Square. A garden built in vacant lots by a Norris Square community group, celebrating Latino culture and heritage. A casita houses everyday artifacts from domestic life in Puerto Rico and in its kitchen residents can prepare meals for celebrations. Photo by Sally Harrison.

In contrast, Fishtown grew from its colonial origins as an urban village, expanding in ethnically identified clusters as different groups arrived from Europe. Its intimate and irregular street grid derived from the geometry of the riverfront, evolved organically with smaller manufacturing sites, churches and graveyards woven into the residential fabric. It maintained a fierce clannish ethos around parish and workplace, 19 but by the 1990s job opportunities had dwindled, housing lost value, crime rates grew. Younger Fishtowners moved from the old neighborhood, leaving a fabric of relatively intact housing and by the early 2000s saw an influx of young, but savvy artist-gentrifiers, many of whom became small-time developers. Seizing on the economic and status advantage of the young creative class and seeking to reverse the decades-long depopulation trend, a commercial/arts corridor was conceived in 2004 on Frankford Avenue. A study touted the advantages of art as a branding agent for commerce and development as well as for its commodity value. So blatantly catering to the middle class taste, there was barely any mention of the very nearby Front Street with its bodegas, dollar stores and check cashing establishments as a potentially competing viable commercial corridor. 20 (Fig. 6.)

IN-BETWEEN TWO WORLDS: A TERRAIN VAGUE

Interactions between the two neighborhoods were rare, resulting from burnished physical as well as social conditions. Racial hostilities had been decades in the making. The collision of street grids at Front Street created a disorienting, discontinuous cross-movement network, a divide reinforced by the elevated rail, darkening the struggling commercial street below.

A vacant seven-acre site that had been the terminus of a defunct rail line stretched along Front Street for several blocks toward the end of the commercial corridor expanding the divide between the two neighborhoods – creating a terrain vague filled with abandoned vehicles and inhabited by small colonies of homeless drug users. The only evidence of border crossing was a narrow beaten path connecting Fishtown to the El stop at Berks and Front Street. The path originated in a break in what was referred to as the Fishtown Wall – a four-foot retaining wall demarking the community boundary.

The NSCA had acquired the site, and to catalyze activity, had developed a market and lunch spot featuring Latino specialties in a small warehouse along the path the El. To build on this the NSCA invited design proposals for the site’s development. Could this no-man’s land become a shared amenity transforming the terrain vague into a connective node between the two neighborhoods? Strategically located, it had transit access to the whole city – potentially a place of larger scale civic intercourse. Proposals followed this ethos of inclusivity looking to develop spaces of mutual interest and encounter, with mixes of uses including commerce, urban horticulture, education, recreation, and entertainment. Underlying patterns of circulation and public space would build in porosity creating multiple cross-neighborhood linkages within and through the site. (Fig. 7.)

But unable to achieve the financial support to develop the site, NSCA sold it to the school district. A magnet school for the creative and performing arts was finished in 2011 – a LEED platinum building that was part of the trend of urban greening that Fishtown had also eagerly adopted. With development funds from the water department the 7 acre site was branded “The Big Green Block” in the zip code “Sustainable 19125.” Virtuous as the sustainability goal may have been, and as appropriate to an inter-community scale a magnet school may be, it did little heal the divide between the two neighborhoods: the school and its elevated playing field fill the site, allowing no informal “loose spaces” that Stevens and Frank speak of that might encourage public encounter. 21 Even the passage to the El stop was swallowed up: a narrow footpath enwalled with chain link fence.

In the end a project so potentially rich in opening up possibilities for building heterogeneous democratic city life, closed the door. Reinforcing a boundary, it became a victory for gentrification; new expensive housing filled in on longtime derelict lots adjacent to the Big Green Block, and developers began to eye land across Front Street. Fishtown continued rapidly gentrifying, with new row housing once valued at $100,000 being sold for five times as much. The Frankford Avenue Arts Corridor was now enlivened with bike racks salvaged from industrial machinery, smartly designed bus shelters, and an annual “energy” festival, with a slew of coffee shops, galleries, and art supply stores all with trendy names, the Rocket Cat Café, the Sculpture Gym.

Despite their sophistication the gentrifiers tend to cling to their parochialism, having maintained fixed boundaries in their own mental maps. A three year resident and art school educated waitress in the Soup Kitchen (not a soup kitchen) yearned for open space but was completely was completely unaware of Norris Square Park only three blocks away. She reported also her boyfriend owned a building on Front Street and was disgusted by behavior of the other occupants of the street – not picking up trash, hanging on street corners etc. The point was confirmed by the North Philadelphia city planner “my Fishtown folks never cross Front Street; they wouldn’t know about Norris Square park.” 22

DESIGNING THE HETEROGENEOUS CITY

With the seven-acre site transformed from terrain vague to the Big Green Block, Front Street has become what a board member of the Fishtown’s community development corporation described as “the sharp boundary… where the real fight is going to happen.” 23 Residents of Norris Square are legitimately fearful of gentrification, especially those who can remember their expulsion forty years ago from the now fashionable Fairmount area. However, in their decades-long isolation in the Badlands, the NSCA managed to consolidate ownership and claim of the neighborhood’s strategic land resources. For-profit developers who know the value of green space have begun to swarm into Norris Square only to be frustrated by the barriers put in place to defend against displacement. 24 Venting on blogs, the would-be gentrifiers accuse the NSCA of hoarding properties some purchased cheaply from the city; others accuse the director’s protective stance toward securing an affordable culturally focused neighborhood as being close to racist.

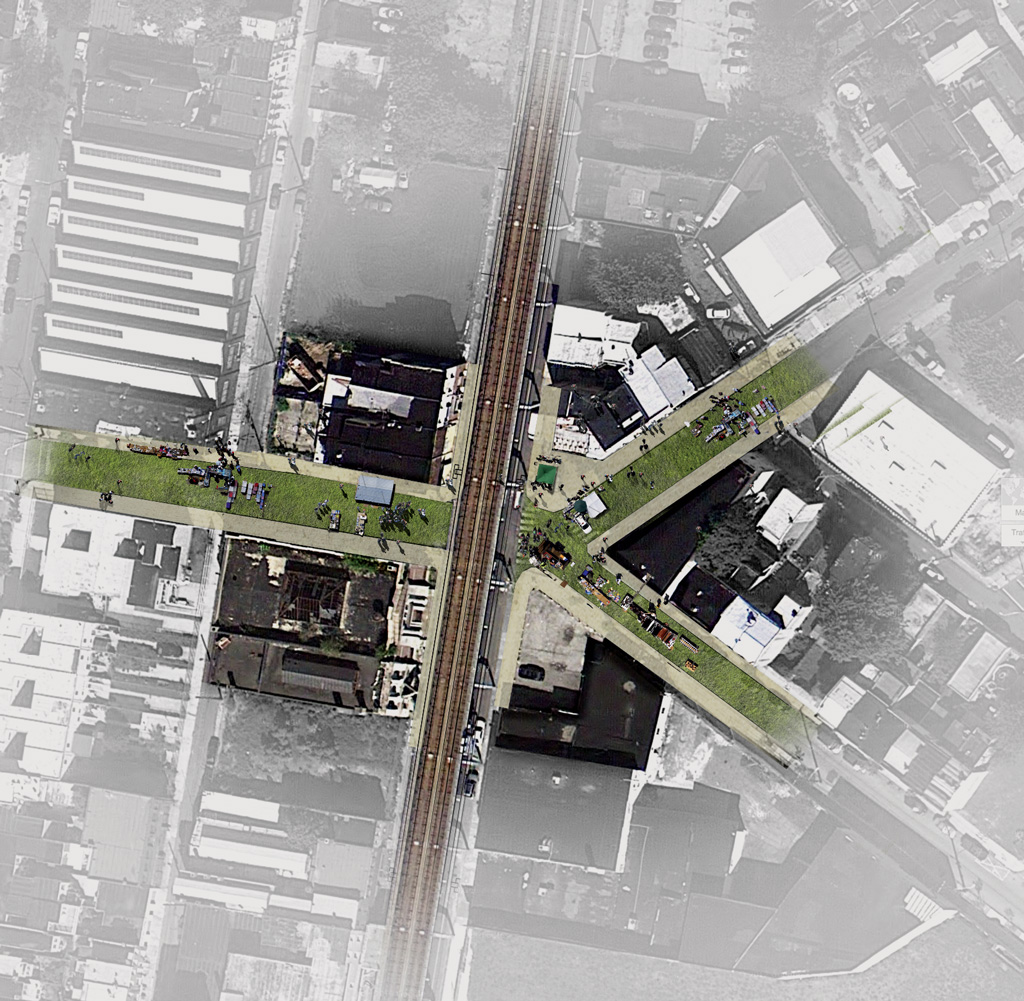

There is indeed a kind of inevitability in this contest: not that Norris Square will be gentrified, or alternatively that it will block all neighborhood change, but that spaces of negotiation will be required. Rather than a boundary that separates or belongs to either one or other of the cultures, the Front Street corridor in all its fragmentation presents the opportunity to create another layer of citiness, a broad irregular seam that loosely laces together the two neighborhoods with spaces and spines of interaction and mutual utility. 25 Design focused on porosity rather than closure of the street edge can allow interpenetrations of all kinds: of light, movement, sight lines, vegetation into otherwise bounded territories. Overlapping programs and heterogeneous public spaces can invite interactions: simple civil contact in a shared environment or passionate debate among co-habiting interests. A landscape proposal envisions crossing the divide by “turfing” the streets as they pass below the El, a temporary installation where spatial continuity can replace discontinuity, and where public encounter and cross-cultural dialogue can energize the breach even as it is becoming ever more contested. (Figs. 8a and 8b.)

And a spatial reminder of the transcendent temporal quality of urban life, it would serve well to reuse the nineteenth century fabric that predates ownership of either competing group. Design speculations transforming Front Street’s uninviting aspect include renovating a historically significant vacant bank as a community market and town hall and developing retail with upper story housing setback from the noise of the El and allowing light to enter the dreary space below. On a site linking Front Street and Norris Square is proposed a hybrid democratic institution, combining library and a maker-space, offering use value to both constituencies, and potential learning and social intersections. In its presence at the border zone. the building both represents the colorful imagery in Norris Square, and offers a physical threshold into the neighborhood. (Figs. 9a and 9b.)

FINDING A ROLE FOR DESIGNERS

The city, framed as oeuvre, as Lefebvre says, “is closer to a work of art than to a simple material product.” 26 In these terms, neighborhoods, especially those built through sustained grassroots efforts, may possess the underlying complexity to withstand exogenous forces if given representation. If designers expand their role beyond the consultant-client product/service-delivery model, they can act both as partners in a shared civic endeavor and as agents capable of representing and advancing the oeuvre. Redressing the banal heartlessness of gentrification can be viewed as a design challenge writ large, where principles of architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design can be brought to bear: context, spatial layering, growth, porosity, pattern, public-private interface, materiality, luminosity.

Designers can first employ their skills to help communities build a layered narrative of neighborhood spatial culture. This narrative can weave together practices and meanings inscribed in the physical environment, representing often hidden strengths – from the front stoop and the corner store that support social and economic interaction; to the multi-functionality of school and church buildings that give new meaning to neighborhood institutions; to patterns of connectivity; to homes that reconfigure to accommodate changing occupancy and informal businesses; to vacant lots and bounded streets appropriated for play and celebration. In the context of gentrification’s bent toward branding the neighborhood as consumable product, visualizing this kind of complicated – often messy – place-identity is ultimately a more potent platform for future development. It corrects asymmetries of power by framing a dignified expression of a collective presence saying: We are here; our neighborhood is valued as a place, not a site of exchange.

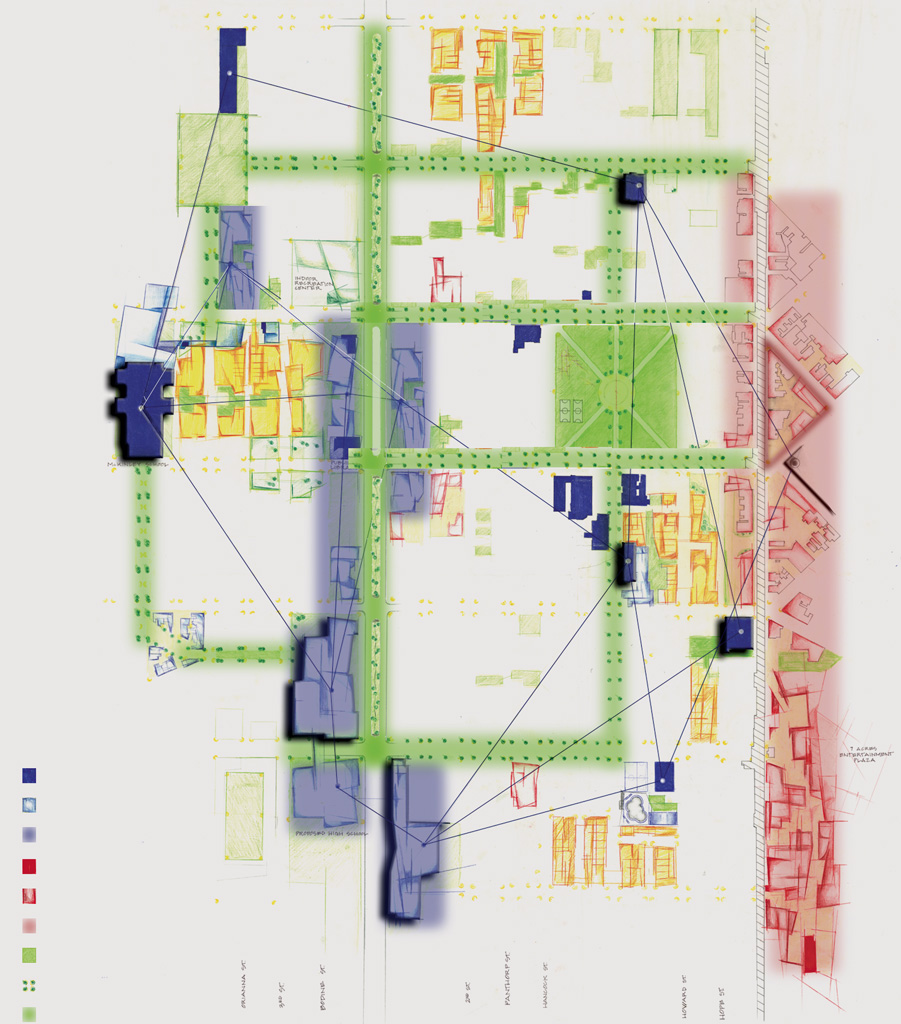

This expression of neighborhood culture forms a core of resistance that initiates habits of analysis and design thinking. Embedded in this holistic conception of place, are information sets that map out sites of opportunity, vulnerability and contestation, and with this knowledge a strategic rather than reactive approach to control of land can be adopted, either by formal acquisition or informal appropriation. Designs that emerges from these explorations of place may look different than concept-driven plans; they would operate on multiple fronts and at diverse scales, employ tactics that energize larger systems, and create new spatial hybrids that take cues from need-driven adaptations. A plan might include the build-up of an identity-reinforcing web of key neighborhood gathering places (grand or modest), while exploring the potential of critical sites in border zones and projecting forays into territories beyond the pale. (Figs. 10a and 10b.)

When the complexity of lived space is valued beyond simple currency of exchange, a broader expression of the city as oeuvre is free to unfold. Now the goal is not just to preserve a community’s “right to stay put,” but having established a secure base, to serve the interests of the next scale of urbanism in the space where different communities overlap. Here, day-to-day contact with others’ spatial habits and expression accumulate. Sometimes highly ambiguous and fluid, the margins can be vigorously engaged, indeed celebrated, as sites of negotiation and contestation, where hybrid forms of collectivity are actualized. If together designers and communities are willing to engage with rather that flee from conflict, they can contribute to a broader authentic discourse on how we shape the city around shared values of a democracy. 27Here designers are not accessories to a narrow agenda, but can orchestrate differing cultural perspectives and visualize spaces of encounter where a mosaic of multiple publics is represented on the larger urban stage.

Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City” in Eleanor Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas, eds., Writings on Cites/Henri Lefebvre (Cambridge MA: Blackwell, 1996), 101.

See: Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996); Loretta Lees, “Guest Editorial” Environment and Planning A 36 (2004): 1141-1150; Japonica Brown-Saracino, The Gentrification Debates (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2010); Sharon Zukin, Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (New York: Oxford University Press 2010).

Derek Hyra, “The Back to the City Movement: Neighbourhood Redevelopment and the Processes of Political and Cultural Displacement,” Urban Studies 52, no. 10 (2015): 1753-1773.

See: Thomas Angotti, “The Gentrification Dilemma” in www.architectmagazine.com/design/the-gentrification-dilemma_o 2012 Venice Biennale; Thomas Slater, “The Eviction of Critical Perspectives from Gentrification Research,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30 (April 2006): 37-757; John Joe Schlichtman and Jason Patch, “Gentrifier? Who, Me? Interrogating the Gentrifier in the Mirror,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 38 (July 2014): 1491-508.

Bryony Roberts, “Looking for the Outside: ‘How is Architecture Political?’,” The Avery Review 5. http://averyreview.com/issues/5/looking-for-the-outside

See: Bryan Bell, ed., Good Deeds, Good Design: Community Service Through Architecture (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2003); Bryan Bell and Katie Wakeford, eds., Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism (New York: Metropolis Books, 2008); John Cary and Public Architecture, The Power of Pro Bono: Forty Stories about Design for the Public Good by Architects and their Clients (New York: Metropolis Books, 2010.); and Kate Stohr, Design Like You Give a Damn 2: Building Change from the Ground Up (New York: Metropolis Books, 2012).

Peter Aeschbacher and Michael Rios, “Claiming Public Space: The Case for Proactive, Democratic Design” in Bryan Bell and Katie Wakeford, Expanding Architecture, 87.

See note 2.

See: Andres Duany, “Three cheers for 'gentrification',” The American Enterprise 3 (Apr/May 2001): 36-39; Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2002) and Richard Florida, Cities and the Creative Class (New York: Routledge, 2005).

Loretta Lees et al., Gentrification (New York: Routledge, 2008), 210.

Lance Freeman and Frank Branconi, “Gentrification and Displacement: New York City in the 1990's,” Journal of the American Planning Association 70 (January 2002): 39-52.

Lynne Manzo and Patrick Devine-Wright, Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications (New York: Routledge, 2014): 141-153.

Derek Hyra, “The Back of the City Movement," cit..

Brooke Havlik, “Eating in Urban Frontiers: Alternative Food and Gentrification in Chicago” (master's thesis, University of Oregon, 2013), 0171N_10846.

Karen Wilson, “Building El Barrio: Latinos Transform Postwar Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Legacies 3 (November 2003): 17-21.

Patricia Haynes, “Philadelphia: A City of Neighborhoods,” in A Patch of Eden: America’s Inner-City Gardeners (White River Junction NH: Chelsea Green Publishing, 1996), 71-116.

Personal Interview with Patricia DeCarlo, January 2015.

Personal interview with Shanta Schachter, July 2014.

Group G, LLC., “Frankford Avenue Arts Corridor,” unpublished report, 2004.

Karen Franck and Quentin Stevens, Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life (London: Routledge, 2006).

Personal Interview with David Fecteau, July 2014.

Personal interview with Wesley Casconne, January 2015.

Interview with Patricia DeCarlo, 2015.

Andrew Jacobs, “Convergent Dwelling: Neighborhood Identity and the Landscape Narrative” (master's thesis in Landscape Architecture, Rhode Island School of Design, 2014).

Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” 158.

Maria Ballesteros et al. eds. Verb: Crisis (New York: Actar, 2010), 168-180.

The funding for research was through a Temple University Research Incentive Grant, and subsequent and future self-funded initiatives.

This paper was presented at the 104th Annual Meeting of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture in Seattle, Washington in March 2016 and published in the conference proceedings, Shaping New Knowledges (Corser Robert and Haar Sharon, eds., 104th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, Shaping New Knowledges (Washington, DC: ACSA, 2016).

Sally Harrison is Associate Professor of Architecture at Temple University in Philadelphia where she serves as Head of the Master of Architecture Program. Prof. Harrison’s expertise is in urban history/theory and social impact design. She is the leader and co-founder of the Urban Workshop, an interdisciplinary university-based collaborative undertaking research, design and design-build projects in underserved urban neighborhoods. Her work is published in books and academic journals and has been recognized in national and international design awards programs. Prof. Harrison received her Master of Architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Harrison is lead author of the article, having conducted design and research for over a decade in the neighborhoods discussed, and most recently on issues of gentrification.

E-mail: sally.harrison@temple.edu.

Andrew Jacobs, Assoc. ASLA, is a Landscape Designer with SALT DESIGN STUDIO in Philadelphia. He has worked overseas and in Philadelphia: training members of a farmer’s cooperative in agroforestry techniques for the Peace Corps in Togo, West Africa; researching historic agricultural and settlement patterns on Easter Island, Chile; and investigating neighborhood identity in Kensington, Philadelphia. Critical to his design thinking is the link between large-scale systems and localized interventions. Andrew graduated with a B.A. in History from Bates College and an MLA from Rhode Island school of Design. E-mail: andrewjacobs2@gmail.com.