Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

The rejection of “boredom” fueled the midcentury reaction against modernism, but little is known about the complicated presence of this mood in the architectural discourse. Far from being a mere rhetorical tool, the quip “Less is a bore” is part of Robert Venturi’s larger interest in boredom and was influenced by his reading of a book referenced repeatedly in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966): August Heckscher’s The Public Happiness (1962). A liberal writer and political activist, Heckscher situated boredom at the core of modern humanity’s alienation. While the concern with boredom was explicitly addressed in the humanities, I suggest that it was taking shape in midcentury architectural polemics under the influence of writings from other disciplines, as well as the emerging artistic practices that were deliberately embracing the “aesthetics of boredom.” Specifically, I will examine Venturi’s reading of Heckscher through two of his (unbuilt) civic projects that directly engage the issue of boredom: Three Buildings for a Town in Ohio (1965) and the entry for the Copley Square Competition (1966).

Millions of people have been suddenly forced to experience “boredom.” Through the global scale pandemic that has resulted in an unprecedented global scale quarantine, boredom has surreptitiously crept into people’s lives. With less to do and even less to post on social media, everyone is getting bored at home. A surge in articles, studies, opinion pieces, and talk shows about boredom draws attention to its drawbacks and, surprisingly, also to its benefits. For philosophers, psychologists, and artists, this is not a new topic. However, it is not very old either. The Oxford English Dictionary traces back the first use of the word “boredom” (whose English etymology is largely unknown) to Charles Dickens’s 1853 Bleak House.1 Boredom as a concept is born with modernity. However, it also indicates the advent of a discontent with modernity itself.

It was a rejection of “boredom” that fueled the midcentury reaction against modernism, but little is known about the complicated presence of this mood within architectural discourse. In one of the most famous (indirect) architectural exchanges, to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s “Less is more,” Robert Venturi retorted, “Less is a bore.” Far from being a mere rhetorical tool, as it is generally assumed, Venturi’s interest in boredom was influenced by his reading of a book referenced repeatedly in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966): August Heckscher’s 1962 The Public Happiness. A liberal writer and political activist, Heckscher situated boredom at the core of modern humanity’s alienation. I suggest that the concern with boredom took shape in midcentury architectural polemics under the influence of writings from the humanities and the emerging artistic practices that deliberately embraced the “aesthetics of boredom.” 2 Specifically, I will examine Venturi’s reading of Heckscher through two of his (unbuilt) civic projects that directly engage the issue of boredom: three civic buildings for North Canton, Ohio (1965) and the entry for the Boston Copley Square Competition (1966).

I contend that boredom in architecture is different from the ordinary mood that engenders yawns and empty gazes. Paraphrasing Venturi’s expression from Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, for him, boredom is a “double functioning element.” 3 On the one hand, it indicates formal design strategies (such as grids and repetitive elements) against which accents and accidents are deployed. On the other hand, and more importantly, it draws attention to specific moods and atmospheres of public spaces where the routines and habits of ordinary life unfold. Today more than ever, it is critical to understand the banal and yet essential practices of the everyday and their relationship to architecture, as “social distancing” measures are threatening the very existence of public spaces.

“Less is a bore” and the “decorated shed” are arguably two of the most significant contributions that Venturi – first by himself, later with Denise Scott Brown – brought to architectural theory. Published six years apart, in 1966 and, respectively, 1972, the two propositions contain the seeds of a curious paradox. The former is a direct critique of the modernist language and re-appropriates ideas about formal and decorative excess previously shunned by modern architects. The latter, while reducing a meaningful building to a structure with applied decoration, is both “more” and “less:” “more” ornament and “less” architecture. Venturi was no stranger to ideas about paradox: from his early projects published in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, he programmatically employed flat and plain surfaces. At the same, he was affirming his predilection for mannerist, baroque and rococo precedents that showcase intricate manipulations of forms and planes.4 On the one hand, he championed flat surfaces in architecture, but on the other hand, he turned toward an architecture of complex and convoluted surfaces. How are we to explain this paradox? How are we to understand this ostensible inconsistency of thought? Is the paradox of “both/and” first articulated as a theoretical position in the “gentle manifesto” for a “nonstraightforward architecture” 5 and later illustrated in his own practice, a rhetorical device meant to ultimately validate any type of approach, or does it, perhaps, stem from different sources?

I propose to examine Venturi’s paradoxical interest in boredom, its simultaneous dismissal and acceptance, through two of his designs for public spaces that I will situate in a broader cultural context. I will show that during the middle decades of the twentieth century, ennui as a shared mood is present on multiple levels, thus creating the underpinnings for social and artistic changes. While visual arts directly confront Boredom both as an aesthetic strategy applied to the object and as a disposition induced in the subject, architects signal its presence mainly as an indicator of the failure of modernism. Against this background, Venturi’s projects for three buildings in North Canton, Ohio (1965) and the entry for the Boston Copley Square Competition (1966) that specifically address this topic, invite a different reading.

BOREDOM AS A CULTURAL MATTER

Ennui, Langeweile, Acedia,Tedium: what do we mean when we talk about “boredom”? Closely examined in philosophy, aesthetics, social sciences, critical theory, literary studies, and visual arts, boredom remains ambiguous, vague, and rarely acknowledged in architecture.

A complicated mood, boredom most often evokes one’s alienation from their environment and even life itself. Certain philosophers, however, have uncovered its contemplative and introspective nature, unexpectedly conducive to creativity and imagination. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Walter Benjamin and Sigfried Kracauer examined the unforeseen delight hidden under the deadening appearance of tedium. Benjamin described boredom as “a warm gray fabric lined on the inside with the most lustrous and colorful of silks.” 6 Kracauer argued that if one is patient enough in her boredom, she will experience “a kind of bliss that is almost unearthly.” 7 Martin Heidegger unveiled the temporal dimension of tedium (the German Langeweile translates as “long while”) and identified three forms of boredom. The most banal is the boredom of waiting in a train station. The most profound creates the attunement of the being to the very nature of philosophy.8

Psychologist Orrin Klapp proposed that the increased use of the word “boredom” between 1931 and 1961 indicates the ubiquity of this mood in modern society.9 In the middle decades of the twentieth century, boredom was experienced as a discontent with everyday life across spaces, geographies, art forms, literary genres, and disciplines. Two specific manifestations of boredom were prevalent during this time.

First, boredom suspends the relationship between the individual and the world, as Alberto Moravia observes in an interview titled “L’Occidente s’annoia” (“The West is Getting Bored”).10 Nothing makes sense, every possible action is futile and therefore no action is taken. In the post-World War II decades, as industrialized societies experience both the thrill of consumerism and the threat of a nuclear war, boredom permeates private lives, as well as the public sphere. Elizabeth Goodstein argues that a generalized skepticism “renders the immediacy of quotidian meaning hollow or inaccessible.” 11 This disenchantment with the world is a pervasive mood in poetry, fiction, and film. Dino, the main character of Moravia’s 1960 novel La noia (Boredom), is a wealthy painter disillusioned with life who develops a neurotic love for Cecilia. Dino stands for an entire generation alienated by its indifference toward and disengagement with itself and the world.12 The characters in Jacques Tati and Michelangelo Antonioni’s films or those in Georges Perec and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s novels experience the emptiness resulted from the broken relationship of the self with the world. From individual houses to suburban developments and urban contexts, boredom renders life meaningless. “What currently marks our public life is boredom. The French are bored,” writes the journalist Pierre Viansson-Ponte in the March 15, 1968 issue of Le Monde. John Keats’ 1956 novel The Crack in the Picture Window is an open critique of the post-war American suburban developments.13 Basing his novel on literature published from 1947 through 1955, Keats identified the main problems of suburban sprawl as financial and land speculation, consumerism, and poor design. All the families live in identical houses, with identical picture windows, equipped with identical furniture and appliances purchased under the pressure of advertising. Tedium is everywhere. In front of their TV sets, everyone eats the same Yummy Gummy mix that comes in “six distinctively similar flavors” creating the illusion of diversity while, in fact, only bringing “gustatorial boredom.” 14

This very boredom, however, becomes the catalyst for change, building the underlying mood for creativity and new artistic expressions. This second manifestation of boredom capitalizes on purposeful disengagement and lack of effect as creative tools. A “dead-pan disenchantment” 15 emerged in artistic practices during midcentury as a conscious approach to liberate the arts from the subjectivity of emotions. Described as “the aesthetics of boredom,” 16 or “the aesthetics of silence,” 17 this tactic invites the viewers to go beyond appearance and commit to a deeper engagement with the work “at a time when there is too facile an appreciation of culture.” 18 The silences and dissonances of John Cage’s music, the objectivity of Merce Cunningham’s choreographies, the focus on the repetitive and the ordinary in Andy Warhol’s works, the affect-less presence of Donald Judd’s art – all share the same intention: to elicit a response from the audience through an artwork completely devoid of emotions and feelings.19 In this space of silence, lies the opportunity for wonder, new forms of criticism, and dialogue with the work. Boredom becomes a deliberate strategy of contemplation and critical judgment.

BOREDOM AND MIDCENTURY ARCHITECTURAL PRACTICES

The midcentury architectural discourse resonates with this overall disposition underlying other artistic practices. The meaning of boredom, however, changes. While visual arts employ ennui as a deliberate aesthetic strategy, architects are apprehensive of the formulaic turn of the modernist language and signal the necessity of renewal. Emerging from consumerism, overstimulation, and leisure, boredom feeds the anxieties of practitioners and architectural critics alike.

For some, the Old World is exhausted and has little to offer to modern life. Such is the case of the Austrian-born architect Josef Frank who, after having lived in New York between 1941 and 1946, moved back to Sweden. In a letter to the Austrian painter Trude Waehner from March 1946, he explicitly manifested his interest in the issue of boredom in art and architecture, wondering why “are the streets and dwellings here so uninteresting?” 20 In two other letters to Waehner from the same year, he admitted his preference for American “rawness,” 21 questioning, rhetorically, “What good is the art here and carefulness in building if everything is so dull?” 22

While sociologists, anthropologists, and cultural critics draw attention to the boredom spawned by consumerism and mass production, architects observe its impact on the built environment. In 1955, Bernard Rudofsky published Behind the Picture Window, a collection of satirical essays on everyday life in the United States and the deterioration of architecture under the pressure of consumerism.23 Titled “On Boredom and Disprivacy,” the concluding chapter criticizes the modern house, encumbered by mechanical devices, as being conducive to solitude, alienation, and boredom. One of Rudofsky’s answers to the problem of modern tedium was imagining the house as an “instrument for living” that would replace the “machine for living” dear to modern architects from Le Corbusier onward. He explained this distinction through the difference between “playing a violin and a jukebox.” 24 While the “machine” responds to the external stimuli received from the user (such as pressing a button on the jukebox) and generates the same response regardless of the user, the “instrument” is attuned to the rhythms and bodily movements specific to each player. As boredom inflicts on people’s lives, the most obvious solution appears to be the quick change – modern individuals falsely believe that their problems will be solved by trading their current house for another one, larger, yet so similar. Rudofsky echoed Søren Kierkegaard’s nineteenth-century reflections on boredom.25 In a critique of consumerism avant la lettre, Kierkegaard condemned an “extensive” response to boredom that involves a variation of the surface instead of a deeper and more substantial change. Bored with the countryside, he argues, people move to the city; bored with their native lands, they go abroad; bored with Europe, they travel to America.26 As an alternative, he suggests, limitations and restraints make one more resourceful and more creative.27 Similarly, Rudofsky noticed that the modern individual’s “periodical changes of address are no more than futile attempts to escape the boredom of his environment.” 28

In their 1963 Community and Privacy: Toward a New Architecture of Humanism, Serge Chermayeff and Christopher Alexander shared Rudofsky’s concerns about the loss of privacy in modern houses.29 While the modern individual’s “anxiety-ridden existence” is fundamentally monotonous, the transparency of their house, along with the deafening sounds of mechanical devices are threatening “the provision for relaxation, concentration, contemplation, introspection.” 30 As “more and more becomes less and less,” overstimulation leads to boredom, the latter being manifested in the proliferation of artificial, machine-controlled environments.31

In addition to consumerism and overstimulation, the relationship of boredom with new forms of leisure raises new challenges for architects. In the early 1960s, British architect Cedric Price along with Joan Littlewood, a radical theater director and social activist, embarked together on the challenging adventure of designing the Fun Palace, with the objective of merging education and leisure. Due to automation and prefabrication, British economy after World War II was predicted to become leisure-driven.32 In this context, Price and Littlewood attempted to make both education and leisure accessible to the working class.33 One of the underlying goals of the project was to address the boredom of the urban dweller who would soon have too much unoccupied time. Price and Littlewood contributed to various promotional pamphlets for the Fun Palace, one of which specifically described the project as a remedy to the problems of tedious routines, urban boredom, and alienation:

Have you changed your job? / Did you want to? / Do you enjoy routine? / Do you make your own discipline? / Do you enjoy disaster? / Do you hate the neighbors? / your own family? / Do you wish to know more about yourself? / your mind? / your emotions? / about science? / art? / history? / politics? / economics? / Do you suffer from boredom? / overwork? / loneliness? / overcrowding? / twelve or more yesses [sic], read on.34

Sigfried Giedion summarized the state-of-affairs in architecture during the middle decades of the twentieth century in his introduction to the 1967 edition of Space, Time, and Architecture, subtitled “Hopes and Fears.” He succinctly described the situation as “Confusion and Boredom:”

In the sixties, a certain confusion exists in contemporary architecture, as in painting, a kind of pause, even a kind of exhaustion. Everyone is aware of it…a kind of playboy-architecture became en vogue: an architecture treated as playboys treat life, jumping from one sensation to another and quickly bored with everything.35

Most famously, in 1966, Robert Venturi quipped, “Less is a bore.” 36

LESS IS A BORE?

Venturi’s 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture begins with “a gentle manifesto” that includes the first references to boredom.

A closer look at the writing process of this manifesto reveals that a particular fragment went through multiple iterations, as shown in the manuscript draft, the article published in Perspecta in 1965, and the final publication. A preliminary version reads:

I like elements which are hybrid rather than “pure,” compromising rather than “clean,” distorted rather than “straightforward,” ambiguous rather than “articulated,” perverse rather than impersonal, accommodating rather than excluding, redundant rather than simple, vestigial as well as innovating, inconsistent and equivocal rather than direct and clear.37

To this sequence, Venturi added – in a hand-written note at the bottom of the page (Fig. 1) – “boring as well as ‘interesting,’ conventional rather than ‘designed’.” 38 Thus, the final version from 1966 included the intentional addition of “boring” and “interesting”:

I like elements which are hybrid rather than “pure,” compromising rather than “clean,” distorted rather than “straightforward,” ambiguous rather than “articulated,” perverse as well as impersonal, boring as well as “interesting,” conventional rather than “designed,” accommodating rather than excluding, redundant rather than simple, vestigial as well as innovating, inconsistent and equivocal rather than direct and clear.39

A close reading of Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture reveals further references to boredom that together constitute the beginning of a consistent, yet overlooked, discourse on tedium and architecture. I am making the argument that, building upon ideas from August Heckscher’s 1962 book The Public Happiness, Venturi’s early interest in boredom primarily addresses issues related to public life and civic spaces. Two of Venturi’s own projects presented in the last chapter of the book specifically bring up the question of boredom in the context of public urban spaces: the redevelopment of the downtown of North Canton, Ohio and the entry for the Boston Copley Square Competition.

“THE PUBLIC HAPPINESS”

In Venturi’s book, the most cited author after Thomas S. Eliot is a lesser-known name: August Heckscher.40 Contemporary with Venturi, Heckscher was an American liberal writer and political activist who served as the chairman of the New School for Social Research, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, and the Parsons School of Design.41 He was a parks commissioner under New York’s Mayor John V. Lindsay, the chief editorial writer at the New York Herald Tribune (1952-56), and the coordinator of cultural affairs at the White House in 1962 under John F. Kennedy. He served as a special consultant on the arts in the Kennedy Administration, was a trustee of the Twentieth Century Fund from 1951 until his death in 1991, and also served as the director of the institution from 1956 to 1967.42

Heckscher was deeply committed to civic matters. He wrote The Public Happiness to signal that, in a world increasingly focused on the happiness of the individual, broader issues such as the happiness of the state and the very idea of citizenship, are being neglected.43 His perspective on politics was founded on the classical Greek notion of polis where good life results from a good and meaningful connection between the individual and the community.44 In the introduction to The Public Happiness, Heckscher recounted his personal awakening to the issue of boredom:

It is very well to worry about satisfying the material needs of the people. […] But these are not the real problems of our society. These real problems are deeper – “boredom,” “loneliness,” “alienation.” Unless the politics of our time can give relevant answers in this sphere, they will not engage the central interest of the citizen.45

Heckscher situated collective boredom at the core of civic responsibilities of the time. He discussed this topic at length throughout the book and dedicated an entire chapter to architectural and urban issues.46 He understood the modern condition as increasingly abstract and remote from “things” and proposed an approach to the world through “an attitude essentially playful, ironical and detached.” 47 Heckscher reclaimed the higher notion of leisure – lost in the modern world – through the notion of play: “Leisure, if it is not to consist of mass orgies and mass boredom, must cultivate an attitude of play.” 48

Many of Heckscher’s arguments revolved around tedium. In the age of communication, assaulted by images and sounds, the modern individual suffers from a profound and debilitating boredom that emerges in response to a hostile world: “It is not the boredom of the haphazard or even involuntary kind; rather it is a deliberate boredom, a carefully contrived blank, a sublime disregard that might be thought worthy of the sage or seer. There is nothing that completely abolishes the world as boredom of this kind.” 49

He observed that a main factor contributing to the alienation of the modern individual is the built environment. Between the fear of overcrowding and that of emptiness, a generalized discontent produces “a psychological state where boredom succeeds to nervous agitation.” 50

Two particular chapters from Heckscher’s book seem to have exercised an important influence on Venturi’s book: “The Approach to Reality” and “Art and Politics.” Based on people’s attitude toward modern life and boredom, the former chapter distinguishes between three groups of individuals. People in the first category “are not really bored” because they are in constant motion, following the trends and fads of their time.51 The second category includes those who make the best of the moment. Lastly, the third category includes “the true citizens of their time.” Without refraining from the pleasures of life, they have liberated themselves from the constraints of consumerism and are thus able to find the deeper meaning of their existence. They are “not bored because even deceptions can be interesting to the enlightened, and not despairing because the only despair can be within themselves.” 52

What people in the third group all have in common, Heckscher believed, is a view of life as essentially complex, an attitude that embraces irony, playfulness, and a “feeling for paradox.” 53 “Complexity,” “irony,” “playfulness,” along with an understanding of modern boredom as the outcome of an existence remote from concrete things, are all ideas that will become central to Venturi’s book.

LIFE IN PUBLIC SPACES

The last chapter of Complexity and Contradiction includes twelve projects designed by the office of Venturi and Rauch. Two of them, both interventions in the public realm, specifically address the question of boredom.

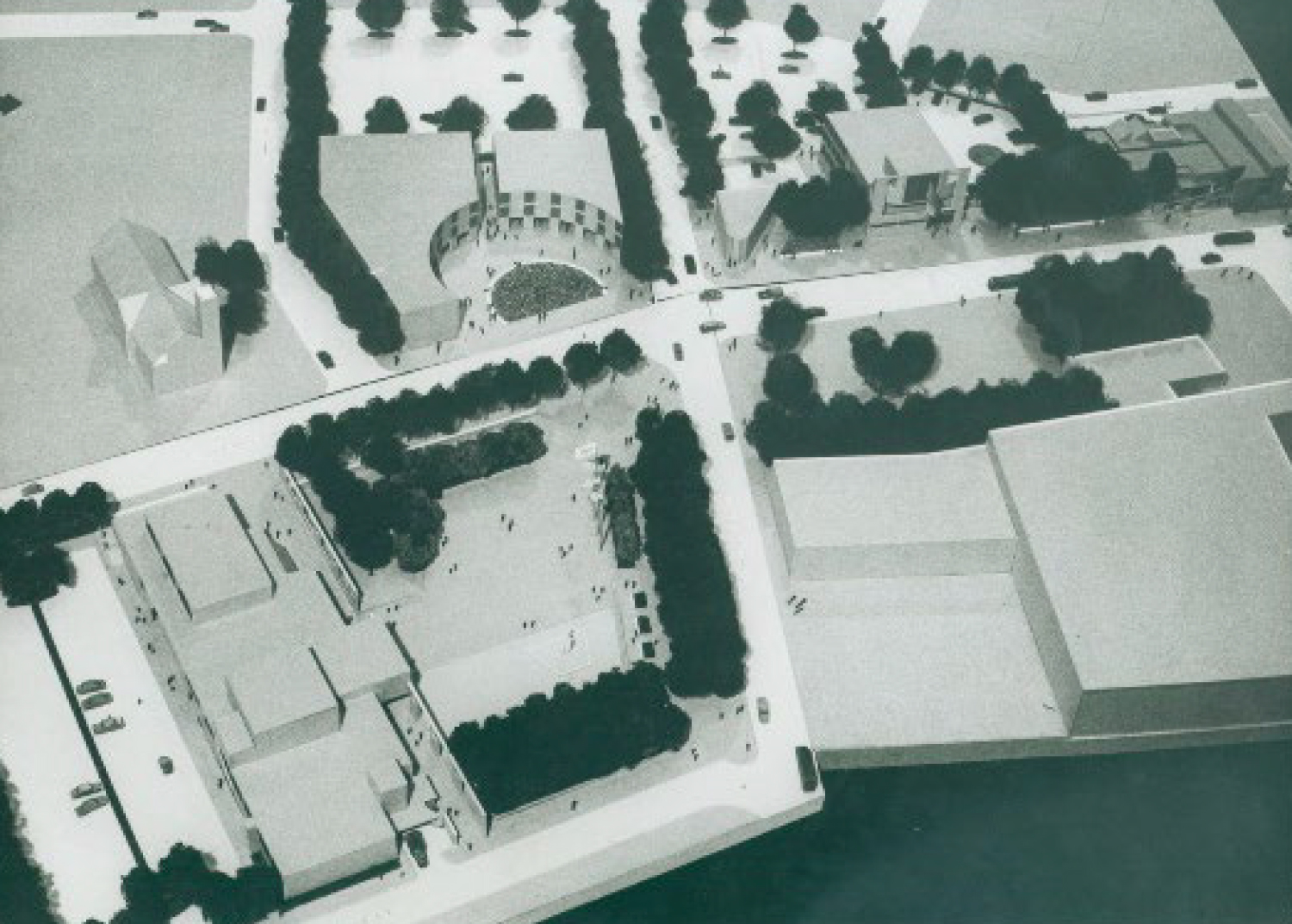

In 1965, Venturi and Rauch made a proposal for the downtown of North Canton, Ohio, hometown to the Hoover corporation, the appliances company. The intervention includes a town hall, a YMCA building, and the extension of the public library (Fig. 2).

Venturi compares the design of the town hall with that of a Roman temple. A freestanding screen – a “partially disengaged wall in front with its giant arched opening superimposed on the two-storied wall beyond” 54 – replaces the classical giant columns and the pediment of the porch. Several perspectival drawings indicate the prominence of this wall that fulfills two functions: it constructs the façade toward the plaza and creates space for a secondary circulation path.

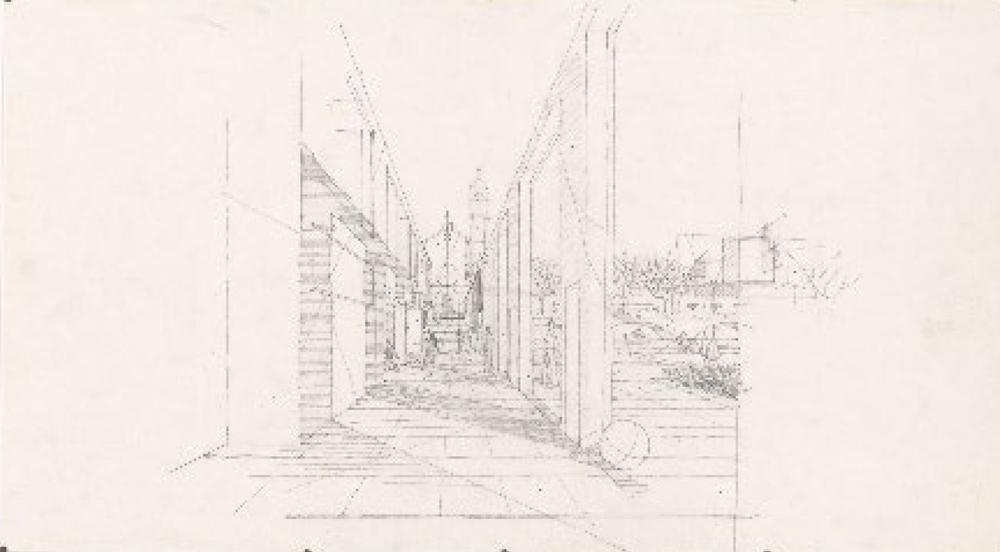

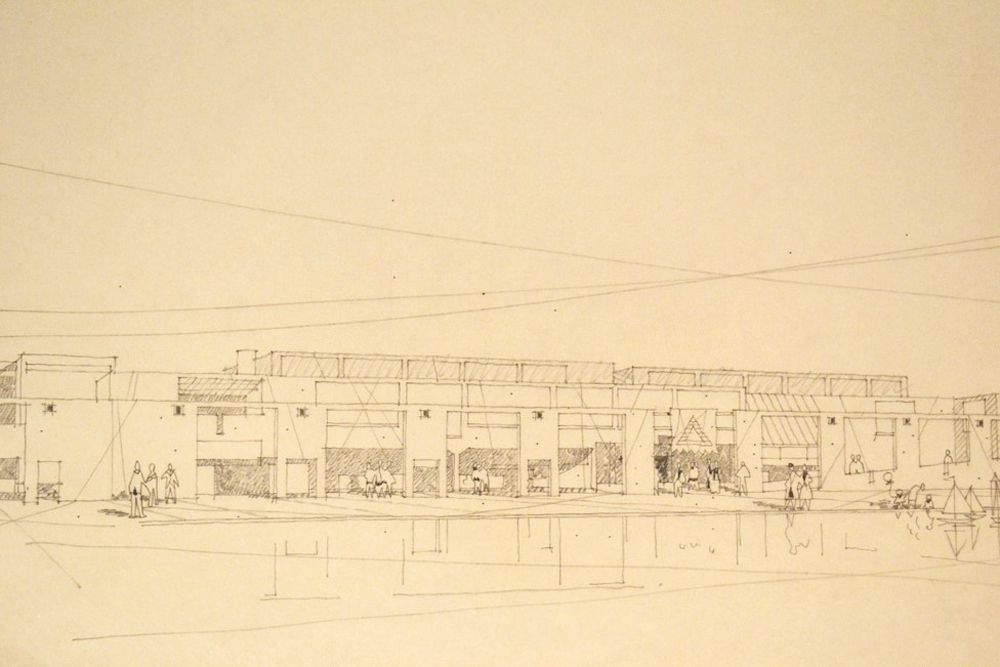

The detached wall constitutes a common theme of the three buildings. The library addition is essentially a wall that wraps around the existing building, and through the openings punctured in this wall, one gets a glimpse of the edifice behind it. Sitting opposite the Hoover factory, the YMCA building has a false front façade whose design was based on a play between different rhythms (Fig. 3).

It has no beginning, middle, or end, “it is just one continuous thing resulting from the constant, even boring rhythm” of the large-scale openings. “The almost constant rhythm of grid-opening is played against the smaller and more irregular rhythms of the two-story building-proper behind. A contrapuntal juxtaposition contrasts the ‘boredom’ of the false façade with the ‘chaos’ of the back façade which reflects the interior circumstantial complexities.” 55 (Fig. 4)

While “boring” here describes the uniformity of monotonous formal rhythms, it also reflects a more significant social condition: a certain tedium of the small town, the routines of factory work, and mass-produced goods assembled in the Hoover facility nearby. These freestanding walls act as stage sets where everyday life takes place. The theme of the detached (or seemingly detached) wall is a recurrent one in Venturi’s early work: from the Pearson House to the Vanna Venturi House and the entry for the National Football Hall of Fame competition, these walls both embody and critique the condition of modern architecture as a thin layer without depth.

Eerily floating in front of buildings, they create a thick, multilayered space where various conditions of inhabitation can unfold. Neither completely solid nor fully open, these walls belong to the building and to the public space, simultaneously separating and connecting spatial and temporal instances. Concerned with the loss of character in modern architecture, Heckscher envisions public spaces as “vast rooms on the outside,” 56 places where civic life can manifest itself. The idea that outdoor public spaces are essential to a healthy city and community is not new, but both Heckscher in his writings and Venturi in his design relate it to the notion of boredom. Losing the ordinary activities that constitute the fabric of public life would inevitably lead to alienation and estrangement.

A close examination of Venturi’s working sketches shows not only the conventional silhouettes of people in motion but also less predictable situations that were rarely rendered in architectural drawings at the time: a person in a wheelchair with their caregiver, toy boats floating on the artificial pond in the center of the plaza, and people skating (Fig. 5).

The rhythms of the YMCA façade, as well as the rigor of the plans designed with practicality in mind, reveal the dullness of administrative duties. At the same time, they evoke the ordinary nature of the quotidian that follows its own course. Heckscher argued that modern boredom is a consequence of individuals being increasingly exposed to “abstractions” rather than “things.” In this process, “what should be concrete in the environment becomes part of an eternal flux and vagueness.” 57 The “dissolution of things” and their loss of meaning result from the excess of objects in a consumer’s culture where over-abundance ultimately leads to indifference. The critical question for Heckscher is how can people escape “from these fogs” and find their way toward a meaningful life. He found a possible answer in the cultivation of a healthy community and public sphere. By turning toward the concreteness of the everyday, Venturi’s project attempted to reconnect the individual with the community and its public spaces. For both Venturi and Heckscher, boredom transcended its immediate reading as a formal composition made of repetitive elements and opens up broader questions about modern society.

Not unlike contemporary fellow artists, Venturi resorted to strategies of “’cool’ persuasion,” but complicated the relationship between disinterest and engagement.58 To embrace everyday life with objective detachment, the approach of the Pop artists whom Venturi admired, is also, architecturally speaking, to translate its tedious routines in built form. Just as an emotion-less “boring painting” awakens in the viewer responses otherwise inaccessible, so do the “boring rhythms” of the façades create a complicity with the inhabitants and their modes of life. In its careful orchestration of the tension between “boredom” and “chaos,” the project celebrates and makes room for public life. While Heckscher rightly recognized the drama of the built environment that generates either boredom, or “nervous agitation,” Venturi proposed a public space that – paradoxically – builds upon, yet overcomes modern boredom. The balance between a uniform field (both as a design background and as the fabric of life itself) and an accent (both as a break in the design pattern and an event in everyday life) constitutes the answer to the question of boredom. This strategy will become clearer in the next project.

The twelfth and last project published in Complexity and Contradiction, the Boston Copley Square Competition entry, co-authored by Venturi and Rauch with Gerod Clark and Arthur Jones, revolves around two issues: “play” and “boredom,” both themes at the core of Heckscher’s Public Happiness (Fig. 6).

Structured on a grid plan, the composition reflects at a small scale the plan of Boston surrounding Copley Square.59 In this context, Trinity Church is an accent in the “three-dimensional repetitive pattern without a climax.” 60 This pattern results from the overlapping of multiple layers – alleys, trees, lampposts, and street furniture. Different “accents” or “slight and violent exceptions” 61 nuance the composition: Trinity Church and its miniature replica, inscriptions of nursery rhymes, variations in elevation. Venturi wrote: “In the context of the ‘boring’ consistent grid inside the square, the chaotic buildings to the north become ‘interesting’ and vital elements of the composition.” 62

The design of the Copley Square proposal builds upon Venturi’s appropriation of Gestalt psychology, another instance where his interests and Heckscher’s converged. Heckscher read the environment in Gestaltist terms of figure and background, structure and void.63 He praised the design of outdoor spaces as exterior rooms and the rich ambiguity of carefully orchestrated relationships between interiors and exteriors that enhance the meaning of a place. Based on Gestalt theories of perception, in the Copley Square design, Venturi attempted to create gradual levels of perception: whereas the plaza is seen as a plain blur from a distance, its details, intricacies, and varieties in pattern, texture, scale, and color are perceived only as one gets closer and closer.64

Venturi’s book is based on the theory course he designed and taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and his lecture notes indicate that he was considering boredom within the framework of Gestalt psychology. Specifically, the outline of the eleventh lecture (on “Composition; Proportion; Unity”) directly addresses these topics:

Unity as the relationship of parts to form a whole. Perceptual basis: Gestalt psychology Necessity of balance of unity with variety; boredom vs. chaos; examples in housing too fragmental or too independent Varying relationships of the parts and the whole to create unity.65

“Boredom” and “chaos,” two extreme positions, have a double role in the Copley Square project: on the one hand, they describe the nature of the built environment, and on the other hand, they reflect the nature of life itself. Venturi emphasized the distinction between European and American lifestyles: while Europeans spend time outdoors in the city in long passeggiata [leisurely stroll], Americans prefer to stay home watching TV.66 Therefore, he replaced the boring empty open plaza dear to Modern architects with a thick plaid, “boring” only in name.

There are opportunities to see the same thing in different ways, the old thing in new ways. As there is not a single, constant accent – a fountain, reflecting pool nor the great church itself, for instance, neither is there a single static focus when you move within and around the square. There is the opportunity for a variety of focuses, or rather for changing focus. The main paradox of this design is that the boring pattern is interesting.67

This twist on boredom concludes Venturi’s description of the Copley Square project. Heckscher decried the loss of a sense of place as “life is spread thinly, in an abstract pattern across the suburban space.” 68 Venturi’s response was to address the void – spatial and social – through the density of a “non-piazza” that offers a variety of experiences, perceptions, and relationships. His design echoes Heckscher’s conviction that “the only real sense of space must come, paradoxically, from a willingness to accept the salutary crowdedness of true urban living. A man’s independence comes not from his being falsely apart, but from being in a meaningful relation with others.” 69 An observation that remains relevant sixty years later, as guidelines for “social distancing,” in place for an undetermined period, threaten to undermine the very nature of our collective existence.

Heckscher recommended that in a world gradually becoming thinner and more abstract, people must cultivate an attitude of play and a sense of irony. These two character traits will provide alternatives to the danger of modern boredom. Echoing Heckscher, Venturi’s design embraces the notion of play. Not only does it “actually” allow children to engage with the space by reading nursery rhymes directly inscribed on walls and offer adults the possibility to experience the full-scale church and its miniature replica in a clever and ironic dialogue (Fig. 7).

“Play” is at the core of the design process itself. Tens of colorful sheets of trace paper fine tune the various layers of the grid in what ultimately appears to be an act of pure design pleasure. The “play” with accents within the thick plaid of the grid relieves monotony and shows how the events of life are anchored in the firm fabric of the everyday.

Unlike most of his peers who used boredom as a rhetorical trope, Venturi employed it as a design strategy. Through repetitive rhythms, the public spaces thus created echo the cadences and tempos of ordinary lives that unfold in specific details from paper boats floating in a pool, to nursery rhymes inscribed on the walls. While the design is not boring, a deliberate monotony invites the inhabitants to pause, examine, and reflect. Whether a series of outdoor rooms (the redevelopment of downtown North Canton) or a thick plaid (the Copley Square project), the public space was designed with its inhabitants in mind. At a time when artists attempted to stimulate their audiences through an art that uses stimuli sparingly, Venturi challenged the potential occupants of these public spaces to ponder over their own lives and environments. He used the modern language to criticize the modernist architectural paradigm. Boredom thus becomes a vehicle for introspection that creates the distance necessary to engage critically with the work.70

Venturi’s projects appear as reflections on Heckscher’s ideas. First, both of them recognized the threat of modern alienation resulted from consumerism and the atomization of society. As civic responsibilities lie at the core of being a well-rounded person, healthy public spaces where people meet, share, and engage with each other, constitute the most basic tool to combat the loneliness and estrangement of the modern individual. Second, Heckscher reclaimed the notions of play and irony as creative strategies against the deadening tedium of modern life. The accidents, reversals, double-functioning elements, and “contrapuntal juxtapositions” in Venturi’s proposals for the two public spaces retrieve the complex architectural experiences that have been lost at the height of modernism. Lastly, Heckscher embraced the concept of paradox as another tactic against the flat line of boredom. Binary thinking and exclusions result in simplifications and ultimately, lack of meaning. The dichotomies boring – interesting, conventional – designed, ambiguous – clear will turn into the “both / and” approach theorized in Venturi’s “gentle manifesto,” as well as in the design of public spaces that accommodate and celebrate the imperfections and uncertainties of life itself.

With the fast pace of change in contemporary practices, the conversation about boredom continues to stay relevant in the architectural discourse today. Confronted simultaneously with visual overload and scarcity of meaning, people feel alienated from themselves and their places. This sense of estrangement results from both the dull and generic architectural production and the impersonal presence of iconic buildings. Moreover, the recent pandemic and physical distancing measures are directly attacking the lives of public spaces and the very notion of citizenship. As people are forced into isolation, boredom is unavoidable, either as a destructive mood, or as a creative tool. An open conversation about contemporary ennui invites to further explorations of moods, dispositions, affects, all ambiguous, yet essential characteristics of the built environment. At its worst, boredom is the malaise of the modern individual confronted with both excess and dearth. At its best, it offers an unexpected potential for contemplation, reflection, and critical judgment.

Oxford English Dictionary online edition, entry “boredom.”

Art historian Sam Hunter identifies the artistic production since the 1960s as “the aesthetics of boredom”: “During the sixties, the ‘angst’-ridden and expressionist outbursts of the best of contemporary art gave way to a new common sensibility based on a conscious program of emotional disengagement, formal rigor, and anonymity of authorship. The change was nothing less than sensational from Action Painting’s agitated brushwork, subjective intensities, and headlong identification with the ‘act’ of creation, to the muted surfaces, reduced forms, and strict intellectual control of so much contemporary abstract painting and sculpture of the ‘cool’ persuasion.” (Chapter 14. “The Aesthetics of Boredom: Abstract Painting since 1960,” Sam Hunter with John Jacobus, American Art of the 20th Century (Englewood Cliffs NJ, USA: Prentice Hall, 1973): 372.

Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 2nd ed. (New York: MoMA, 2002), 34-40; or. ed. (New York: MoMA, 1966).

Ibid., 13.

Ibid., 16.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiederman (Cambridge MA, USA: Belknap Press, 1999); or. publ., 1982; written between 1927 and 1940.

Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans. Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge MA, USA.: Harvard University Press, 1995), 334.

Martin Heidegger, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, trans. William McNeill and Nicholas Walker (Indianapolis IN, USA: Indiana University Press, 1995), 59-169.

Orrin Klapp cited in Peter Conrad, “It’s Boring: Notes on the Meanings of Boredom in Everyday Life,” in Qualitative Sociology 20, no.4 (1997): 466.

“[La noia] essenzialmente, è il prodotto di un’alienazione. Ossia l’interruzione del rapporto tra l’uomo e la realtà e, dunque, tra l’artista e la materia, o se si preferisce tra il soggetto e l’oggetto.” [Boredom is essentially the product of alienation. That is the interruption of the relationship between man and reality and, therefore, between artist and matter, or as it were between subject and object. - Transl. by the Author] Interview with Alberto Moravia, republished in Alberto Moravia, La noia (Florence, It.: Giunti Editore, 2019), 303; Engl. ed.; Boredom (New York: New York Review, 2005):

Elizabeth Goodstein, Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford CA, USA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 4.

“The feeling of boredom originates for me in a sense of the absurdity of a reality which is insufficient, or anyhow unable, to convince me of its own effective existence. […] For me, therefore, boredom is not only the inability to escape from myself but is also the consciousness that theoretically I might be able to disengage myself from it, thanks to a miracle of some sort.” [Transl. by the Author.] Moravia, La noia, 5-6.

John Keats, The Crack in the Picture Window (Cambridge MA, USA.: The Riverside Press, 1956).

Ibid., 82.

Hunter, American Art, 372.

Ibid.

Susan Sontag, “The Aesthetics of Silence,” in Styles of Radical Will (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1969), 3-34.

Hunter, American Art, 372.

Recent scholarship has examined the presence of Boredom in midcentury art: Jonathan Flatley, Like Andy Warhol (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017); Tom McDonough, ed., Boredom: Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge MA, USA: The MIT Press, 2017); Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge MA, USA.: Harvard University Press, 2012).

“I am now preoccupied here with the problem of boredom in art and architecture.” Josef Frank to Trude Waehner, March 2, 1946, quoted in Christopher Long, Josef Frank: Life and Work (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2002), 239.

Frank to Waehner, May 4, 1946, quoted in Long, Josef Frank, 239.

Frank to Waehner, May 30, 1946, in Long, Josef Frank, 240.

Bernard Rudofsky, Behind the Picture Window (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955).

Ibid., 201.

Søren Kierkegaard, Either/Or, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 1987); or. ed., Enten-Eller (Copenhagen, 1843).

Ibid., I 263, 291-92.

Ibid., I 264, 292.

Rudofsky, Behind the Picture Window, 198.

Serge Chermayeff and Christopher Alexander, Community and Privacy: Toward a New Architecture of Humanism (Garden City NY, USA: Doubleday, 1963).

Ibid., 74-77.

Ibid., 78-79.

Stanley Matthews, From Agit-Prop to Free Space: The Architecture of Cedric Price (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007), 10.

Ibid., 68.

Ibid., 92.

Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time, and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge MA, USA.: Harvard University Press, 1967), xxxii.

Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction, 17. While later in life Venturi will allegedly regret this statement, it remains relevant in the context of the midcentury architectural discourse that has never been examined before and which goes beyond the conventional understanding as a clever response to Mies van der Rohe’s modernist dictum.

Manuscript draft of Complexity and Contradition, The Venturi Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania, Box 225.RV.157.

Ibid.

Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York: MoMA, 1966), 6.

The first time Venturi cites Heckscher is at the outset of his book, at the beginning of the second chapter (“Complexity and contradiction vs. simplification and picturesqueness”).

Eric Pace, “August Heckscher, 83, Dies; Advocate for Parks and Arts,” The New York Times, April 7, 1997, online edition, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/07/nyregion/august-heckscher-83-dies-adv..., accessed January 15, 2020.

Archives of the Century (website), https://archivesofthecentury.org/myportfolio/august-heckscher-2/, accessed on January 20, 2020.

August Heckscher, The Public Happiness (New York: Atheneum, 1962), v.

Ibid., vi.

Ibid., v.

Ibid., 253-74.

Ibid., viii.

Ibid., viii.

Ibid., 79.

Ibid., 254.

Ibid., 101.

Ibid.

Ibid., 102.

Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction, 124.

Ibid., 126.

Heckscher, The Public Happiness, 256.

Ibid., vii.

Hunter, American Art, 372.

Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction, 130.

Ibid., 130.

Ibid., 132.

Ibid., 130.

Heckscher, The Public Happiness, 257.

Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction, 132.

The Venturi Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania, Box 225.RV.187.

Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction, 133.

Ibid., 132.

Heckscher, The Public Happiness, 270.

Ibid.

This idea is indebted to the work of cultural theorist Sianne Ngai who writes on “ugly feelings” and contemporary aesthetic categories. She argues that the temporal dimension of the “interesting,” in conjunction with its semantic blankness, opens up the space for aesthetic judgment by returning to the object qualified as “interesting,” discussing and examining it. See Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge MA, USA.: Harvard University Press, 2004), and Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories. Similarly, I argue that the concept of boredom invites a form of critical engagement with the work.

The author would like to extend special thanks to Heather Isbell Schumacher, Archivist, and William Whitaker, Curator and Collections Manager, at the Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania for making possible what seemed unachievable.

Figures 1-7: images © The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania by the gift of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown.

Andreea Mihalache is an Assistant Professor at Clemson School of Architecture, where she teaches design, architectural history and theory, and visualization. Her interests cover the history and theory of architecture and visual culture from mid-century onward; collective and individual memory; domesticity and the everyday; philosophy and aesthetics. Her research has been published in edited volumes and journals and presented at national and international conferences. Her current scholarship examines mid-century architecture and visual arts from the perspective of boredom. She is working on a book manuscript titled Metamorphoses of Boredom: Bernard Rudofsky, Robert Venturi, and Saul Steinberg for the University of Virginia Press. E-mail: amihala@clemson.edu