Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

“If you like simple forms in art, you will not make complicated ones in architecture,” wrote Donald Judd in his 1993 essay “It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp.” Judd went on to emphasize that other forms of design are indeed art, but a simple conversion of art into architecture or furniture does not make good architecture or furniture.

Internationally, Judd is perhaps one of the most well-known American artists of the mid-twentieth century. His carefully constructed boxes seem to have been tailor-made for the fast pace of our cultural consumption, even fifty years before Instagram has solidified our voracious appetite for the generic, yet instantly identifiable. Judd’s rigor and devotion to modesty, purity, craft, precision, and proportion is evident in and even synonymous with his artwork. Judd’s work has been collected and shown by dozens of the most reputable modern art museums all over the world.

Less well-known, however, are his writings, architecture, and furniture. Five of his architectural works, from the later years of his life, are currently on view at the Center for Architecture in New York, in the exhibit entitled Obdurate Space: Architecture of Donald Judd, curated by Claude Armstrong and Donna Cohen. The exhibit is a welcome complement to the recently renovated Judd Foundation in Soho, a several minute walk away, where his art and attitudes on architecture can be seen in the flesh.

The recent renovation of his cast-iron building, which he purchased in 1968, encapsulated the larger context in which Judd envisioned his work.

In a 1989 essay on his 101 Spring Street building, he wrote:

I thought the building should be repaired and basically not changed. It is a nineteenth-century building. It was pretty certain that each floor had been open, since there were no signs of original walls, which determined that each floor should have one purpose: sleeping, eating, working.

This prescribed how ARO approached the renovation of the building when they began working on the project in 2005. With a robust team of consultants, ARO first engaged in five years of intensive research and design, and finally began construction in 2010. The renovated building, which opened to the public in 2013 as the home to the Judd Foundation,

is as close a rendition of Judd’s New York home as one could imagine.

The new space retains all of Judd’s own interventions in the space - from new flooring and ceilings, to plastered walls, built-in bookshelves, mezzanine levels and sleeping lofts. Brand-new mechanical and electrical systems were in most cases invisibly integrated throughout the building, making this a highly-controlled machine that happily takes a backseat to let the original character of the spaces shine center stage. Judd’s custom designed furniture and constructions were placed back in their original locations to offer us a near-exact snapshot of how Judd created his own environment. It is a rare opportunity to see an artist’s work installed exactly as he envisioned it. As Judd later wrote about the installations at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, “it takes a great deal of time and thought to install work carefully. […] Somewhere, a portion of contemporary art has to exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be.”

The parallels between his most well-known works and his design for 101 Spring are easy to draw. Suddenly, his aluminum boxes - a series of which is wall-mounted on the ground level of the building - can be understood as a sequence of spaces, enclosures that are as much exploring the space they frame within them, as the negative space that they shape between them. In much the same way, Judd’s consideration of each floor as programmatically separate can be understood as defining individual units that come together as part of the larger whole. The staircases that connect the floors were left in their original used state, lined with eclectic wooden masks and other small, collected objects. The barrier between these dark sloping spaces and the rectilinear open spaces, naturally-lit from an abundance of large windows, is distinctly marked - sometimes with doorways, other times with heavily narrowed passageways. Judd’s mark on the space is most prominent on the upper floors. On the third floor, he lightly pulled the floor away from the wall to create a thin reveal; a subtle detail (a nod to Carlo Scarpa, perhaps?) that makes a big impact on the overall space. The floor seems to float as a solid plane, interrupting the precision of the box. On the fourth floor, the wood floor is mirrored with a wood ceiling, creating two parallel planes between which we occupy space. On the fifth floor, the floor wraps up onto the wall, with baseboards of the same oak. Once again, Judd’s intervention is simple, but effective; we lose the purity of the ninety-degree angle where we expect white wall and wood floor to meet.

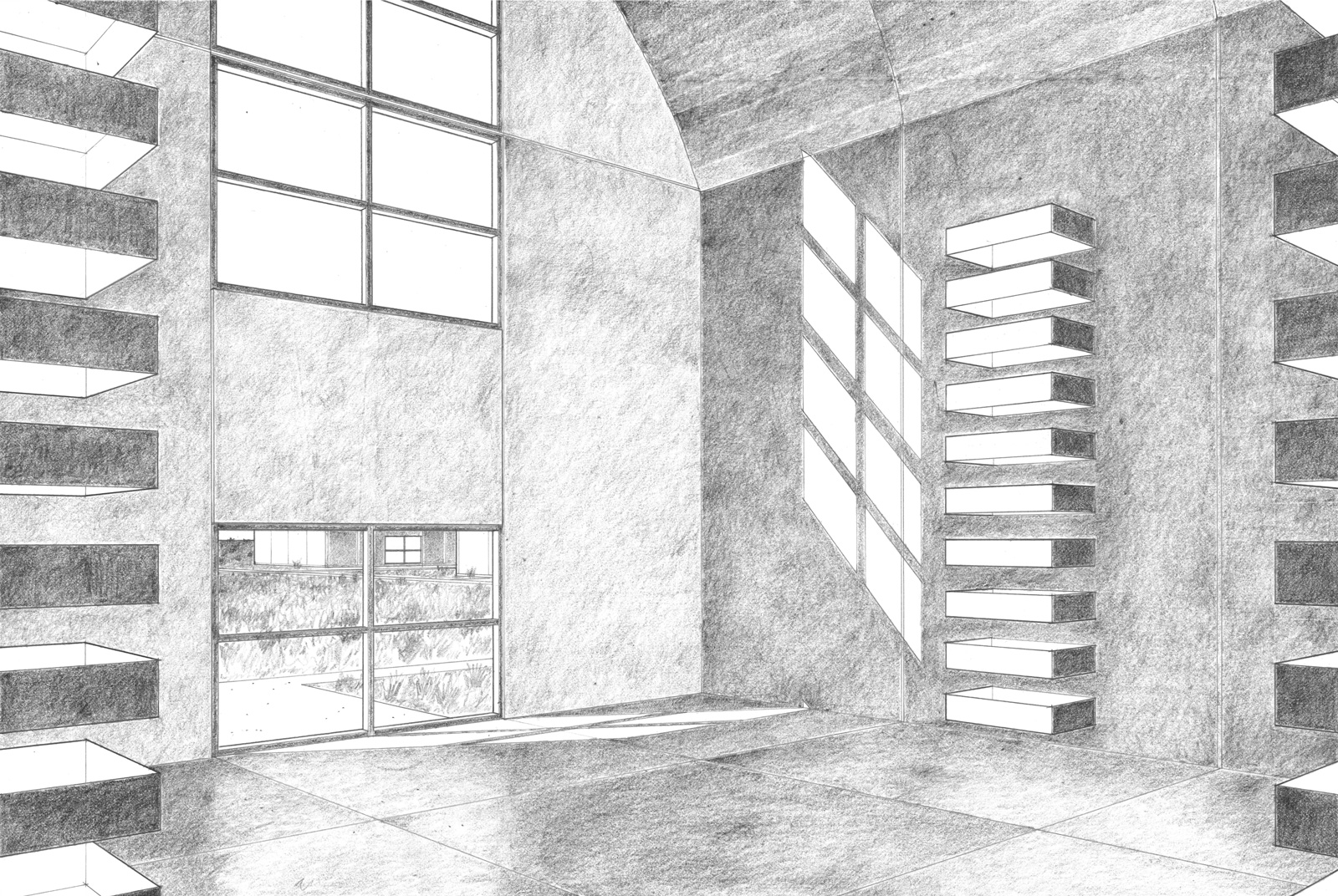

The exhibition Obdurate Space: Architecture of Donald Judd, currently on view at the Center for Architecture in New York, is a striking new view of the evolution of Judd’s architectural works. Curated by architects Claude Armstrong and Donna Cohen, two of Judd’s assistants, the show focuses on built and unrealized architectural projects, designed between 1984 and 1994. Armstrong and Cohen reveal five projects that are part of a largely unknown body of work - Eichholteren on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland; the Concrete Buildings in Marfa, Texas; an archive and office building for Kunsthaus Bregenz (Austria); a lakefront proposal for Cleveland, Ohio; and Bahnhof Ost in Basel. They are shown through archival drawings, models, and photography. For as well known as Judd’s art is in the architecture community, for the most part (his Marfa work being the exception), Judd’s architecture is almost universally unknown.

From the first explorations of space, interiority, and scale in his former residence at 101 Spring Street, to his expanded architectural-scale interventions in his series of Marfa properties, to the later buildings presented in the show, we can see Judd’s effort to develop his architecture as an independent branch of his work. As he wrote in 1993, “the configuration and the scale of art cannot be transposed into furniture and architecture.”

It is easy to question this assertion. Especially as seen in 101 Spring Street, there are undeniable predilections linking the art and the architecture. As the curators note in texts for the show, Judd obsessed over panelization, joints, and proportion. Decisions were intentional. In his Marfa projects, Judd desired to find a material that was structural and consistent throughout - something that had the same finish on both sides. Reinforced concrete was an obvious and easy choice. The similarity between reinforced concrete - thin, uniform, structural - and his beloved material of choice for art, aluminum - thin, uniform, structural - is obvious. If we proportionally scale up the aluminum art works to the scale of his architecture, the 0.25 in. [0,63 cm] thick metal is now 4 in. [10 cm] thick concrete. But its intention is identical. The context is similar as well: Marfa, a scaleless and vast landscape, identical to the scalelessness and vastness of a white gallery wall. Both contexts add monumentality and significance to a box hung on the wall, or a box on the ground.

Of course, there are details that must be altered. Consider, for example, the way Judd’s aluminum boxes are built: the corners are not mitered. Rather, the top plan is butt jointed, sitting upon the side of the box, much like a lintel sitting upon a post. Judd’s large scale concrete sculptures are the same. The bases, however, are slightly different. In his plywood and aluminum art, he matches the top and bottom lengths - the sides sit upon the bottom. In his larger scale concrete works, the sides pass the bottom, which is between the sides. These are not circumstantial details. Judd struggled to find a way of connecting precast concrete panels together. Perhaps he should have taken a lesson from Wallace K. Harrison, who is best known for his large-scale urban work with the Rockefeller family in New York but also built thousands of precast and site-cast concrete houses in Puerto Rico, using integral weld plates to seamlessly attach flat site-cast concrete panels.

However, what the projects in the exhibition highlight, particularly as evident when seeing the buildings in model form, in his later architecture, Judd made effort to separate these works from his art. Most notably, in his buildings he stayed away from flat roof planes.

Of the four buildings shown in the exhibition (let us consider Judd’s proposal for Cleveland, a hyperbole of the infamous Burnham plan, a landscape proposal), only one project has a flat roof - Bahnhof Ost, which was a collaboration with Zwimpfer Partners and Burgen Nissen Wentziaff, and the design responsibilities are ambiguous. Eichholteren was primarily an interior renovation and reorganization of a pitched roof structure, and Judd’s Concrete Buildings in Marfa and office and archive in Bregenz have arched vaulted roofs.

This departure from an oeuvre otherwise dominated by cubic or rectilinear structures is intriguing. Three potential explanations come to mind - all of which are plausible simultaneously. First, as Rob Whitehead has pointed out in his 2015 essay “Ten Concrete Buildings: Donald Judd’s Incomplete Integrations of Art & Engineering,” Judd sketched the arched vault after five years of roof repairs on a flat concrete roof had not stopped the consistent leaking. Perhaps Judd had not been able to devise a flat roof that did not leak. Modern architecture is full of leaks, from Le Corbusier to Gehry and most in-between. A second explanation for his tendency towards arched vaults might point to the influence of Lauretta Vinciarelli, who, as the curators note, had collaborated with Judd from 1980 onward. She introduced Judd to contemporary architecture, especially “her belief in the innumerable possibilities inherent in long-established archetypal forms of building construction.”

Lastly, it is perhaps no wonder that the vaulted arch was used in Judd’s work, considering that Aldo Rossi was taking Venice by storm at the end of the 1970s and into the mid-eighties. In his later writings, Judd describes a particular detail from his designs for 101 Spring Street: the custom steel oval sinks he had made for the upstairs bathroom. The oval is not a form you would generally associate with Judd’s artwork, which was exactly his intent. As he notes, “these were designed directly as sinks; they were not a conversion; I did not confuse them with art.”

Judd was intentionally seeking to visually separate his art and architecture, so that even if created by the same hand with the same predilections, they would be viewed as separate bodies of work. As Obdurate Space makes clear, while Judd’s architectural body of work is nowhere near as extensive as his art work, it is worth celebrating in its own right.

The exhibit, Obdurate Space: Architecture of Donald Judd, is open at the Center for Architecture (536 LaGuardia Place New York, NY 10012) through March 5th, 2018. Special thanks to the curators, Claude Armstrong and Donna Cohen, for bringing this body of work to life in the exhibit, to the Center for Architecture for hosting the exhibit, and a special thanks to Adam Yarinsky, Principal at ARO, for an insightful tour around his spectacular renovation of the Judd Foundation at 101 Spring St. New York, NY 10012.

Figures 1 and 2: photos © of Erik Bardin.

Figure 3: image by Hector Garcia, University of Florida.

Figure 4: (a) model by Levi Weigand, University of Florida; (b) rendering by Olivia Alfonso, Laura Rodriguez, Zachary Wignall, University of Florida.

Figure 5: drawing by Claude Armstrong and Donna Cohen, 1987. Donald Judd Art © 2017 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Image © Judd Foundation.

Figure 6: drawing by Claude Armstrong.

Figure 7: photo © of Center for Architecture (CFA).

Kyle May is an architect and critic based out of New York City. He is a Principal at Kyle May, a critical architecture practice which he founded in 2014. He also co-founded and serves as the Editor-in-Chief of CLOG, a print journal that aims to slow the rapid pace of discourse and provide a platform for the discussion of currently pressing and relevant subjects, which has published 15 titles since 2011.

Julia van den Hout is a New York-based architecture editor and curator, and Director of the communications studio Original Copy. Julia is also a Co-Founder and Editor of CLOG. From 2008 to 2014, she was the Press Director at Steven Holl Architects.