Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Climate change puts the edge between land and sea in sharp relief; sea level rise is essentially a condition of drifting littoral edges.As rising seas threaten to encroach on land-based territories, cities and nations have responded by attempting to fix the edge at a moment in time, blocking the sea’s insidious creep. Atolls formed by coral reefs are mobile, living geographies, which resist attempts to harden their perimeter through structures such as seawalls. We explore how ideas and imaginaries associated with the “edge” between sea and land in the atoll-nation of Tuvalu illustrate competing “riskscapes” and objectives associated with the actors involved. This essay explores this interplay between politics, aid, technocratic solutions, media representations, global aspirations, local ambitions, and climate risk in Tuvalu through an examination of past/future seawalls and other proposals (realized and unrealized) for controlling atoll edges. Through the cases, we seek to re-politicize the edge, unpacking the difficulties surrounding adaptation issues in small-island states, and explore alternative models of “resilient edges” for atoll-dwellers living with climate changes.

Tuvalu is one of the five nations in the world composed entirely of coral atolls: low-lying, sandy islands typically only a few meters above sea level. Atoll nations have been framed by global media as “sinking islands,” the first nations to disappear entirely as a result of rising seas. Tuvalu is one of the smallest nations on the planet, home to around 11,000 people across nine atoll communities,1 though today more than half the population is squeezed on to the capital at Funafuti (Fig. 1). With little in the way of local industry, the majority of the nation’s economy comes from aid, remittances, and sales of fishing licenses to international vessels.

TUVALUAN CLIMATE RISK

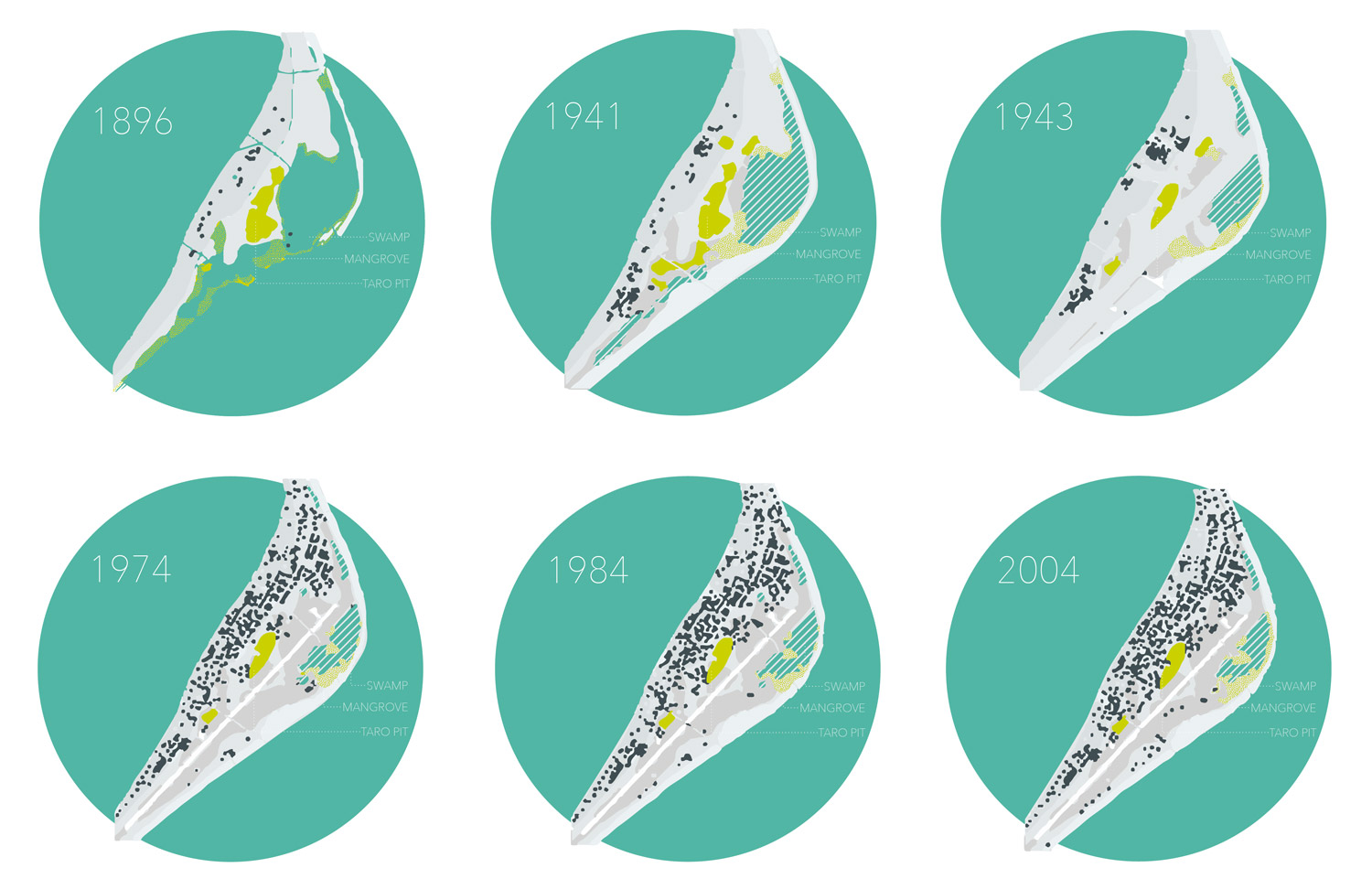

Climate change is already a concern on such low-lying islands, and rates of sea level rise in recent decades have been over three times faster in the area surrounding Tuvalu than the rest of the world.2 However, disentangling climate change impacts from other natural and human caused processes is tricky. King tides - extra high tides caused by the gravitational pull of the full moon - now cause inundation across Funafuti, especially in the area surrounding the airstrip. However, reconstructed cartographies suggest that this flooding may be caused or amplified by increasing construction in low-lying swamps (Figs. 2,3).3 Similarly, the salinization of fresh groundwater is linked to over-extraction from delicate freshwater lenses as well as from rising sea levels and inundation.

Climate change is also associated with increasingly frequent and severe cyclones, and past storms indicate just how damaging these can be for Tuvalu’s atolls. Cyclone Bebe in 1972 flattened 90% of Funafuti, though this was likely amplified by the low-grade clapboard housing stock built following the decimation of the settlement during WWII bombing runs. At only a few meters above sea level, Tuvalu is extremely vulnerable to storm surges; this was illustrated on March 14, 2015, when an elevation in sea level caused by Hurricane Pam, tracking 500 mi. [805 km] away, caused severe flooding on the outer islands and displaced 45% of Tuvalu’s inhabitants. Not only is there no high ground, but only one structure in Tuvalu - the government building on Funafuti - reaches three stories.

This risk to the physical ground of Tuvalu is made more complex by the dependence of national oceanic territory on the ground’s continued existence above sea level. The United Nations Conference on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS)4 stipulates a 200 nautical mi. [370 km] Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) offset of the shoreline of coastal nations. This allows nations such as Tuvalu rights to explore for and use marine resources including power production from wind or water, oil reserves, and most importantly for Tuvalu, fish stocks. For Tuvalu, the EEZ amounts to about 900.000 km2 [350,000 sq. mi.] of territory; more than 30,000 times as much as Tuvalu’s ground area (26 km2 [10 sq. mi.]). In order to claim an EEZ, an “island” must be “a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide” 5 and oceanic territories are usually measured from a baseline established by the low-water line. When islets or even entire atolls no longer emerge from the seas at low tide, these baselines will disappear and submersion may eliminate a state’s claims to oceanic territory. While some have suggested that submerged islands may form a special (but not yet defined) category, we can imagine the possibility - particularly given the current territorial contestations in the South China seas - of remaining dry nations attempting to claim that territory in cases of prior overlapping maritime boundaries, particularly given the limited political capacity of small island states. If all of the islands making up a nation are submerged, island states may furthermore lose their status as sovereign states, since they no longer have sovereignty over land or seas.6

Preserving land for both inhabitation and sovereignty is a primary concern for Tuvalu and its benefactors, and these difficult implications of rising seas contribute to Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga’s visceral representation of Tuvalu’s risks:

No national leader in the history of humanity has ever faced this question. Will we survive or will we disappear under the sea? I ask you all to think what it is like to be in my shoes. Stop and pause for a moment. If you were faced with the threat of the disappearance of your nation, what would you do? 7

However, as the interplay of climate risk and other factors above suggests, reductionist climate change narratives may obscure the complexity of the forces at play, and in doing so may also obscure possible adaptive strategies which effectively navigate the interplay between climate change, atoll systems, and Tuvaluan livelihoods. Unpacking Tuvalu’s fluid context is a necessary step in shedding the media’s fetishized representation of a sinking island nation.

Climate adaptation is inevitably a contested process where different stakeholders and experts vie for the best outcome within their worldview. Structural measures such as seawalls, which define coastal edges, are often presented as “solutions” to rising seas, a dubious claim in Tuvalu where the future impacts of climate change are decidedly complex and uncertain. Suva-based geographer Patrick Nunn describes the “...‘seawall mindset’ in the Pacific Islands, whereby community leaders, following advice from ‘experts’ and observing urban solutions to shoreline erosion, believe that hard artificial structures are the only possible adaptation option in rural areas. The result has been that millions of scarce funds have been poured into constructing seawalls that invariably create new, unanticipated problems and collapse after a year or two.” 8 His observation speaks to how imaginaries of risk and resilience, or “riskscapes,” inform the scope of desirable adaptation responses by particular groups and individuals.

Müller-Mahn defines riskscapes as a “multi-layered” landscape of actual spatial risk superimposed upon “the perceptions, knowledge, and imaginations of the people” who inhabit that space. A seawall - or any adaptation activity - is a response to real risks combined with the perspectives and lived experiences of actors involved.9 We argue that key to understanding the selection of adaptation projects in Tuvalu is understanding the diverse, even competing, riskscapes and resilience imaginaries of the actors involved.

FLUID CONTEXT

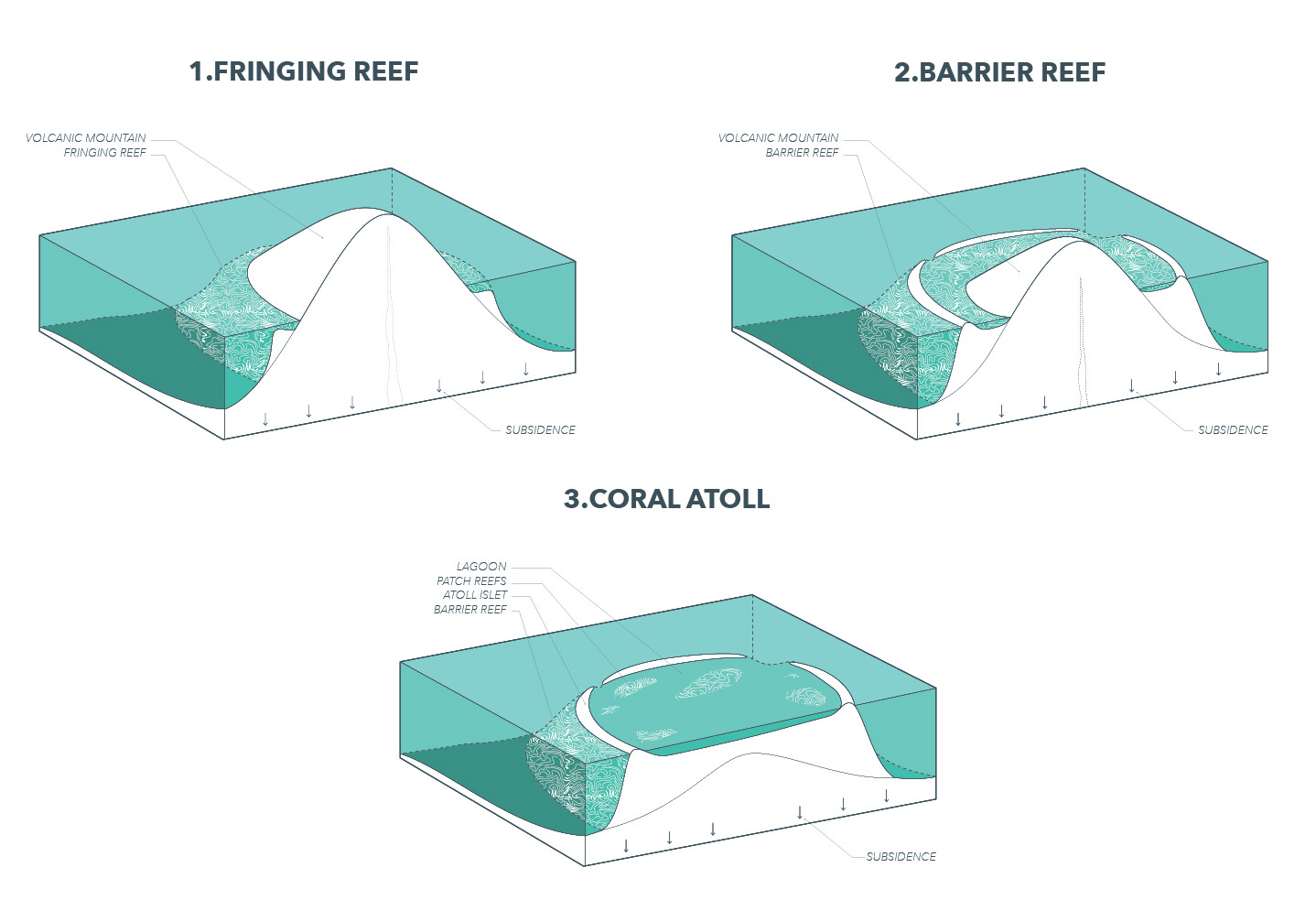

Coral atolls are dynamic, living geographies. They are built from the fringing reefs of subsiding volcanoes, which accumulate sediment and form barrier islands. As the volcanic cone submerges entirely, the reef continues to grow, leaving the surrounding ring-shaped atoll formation (Fig. 4).

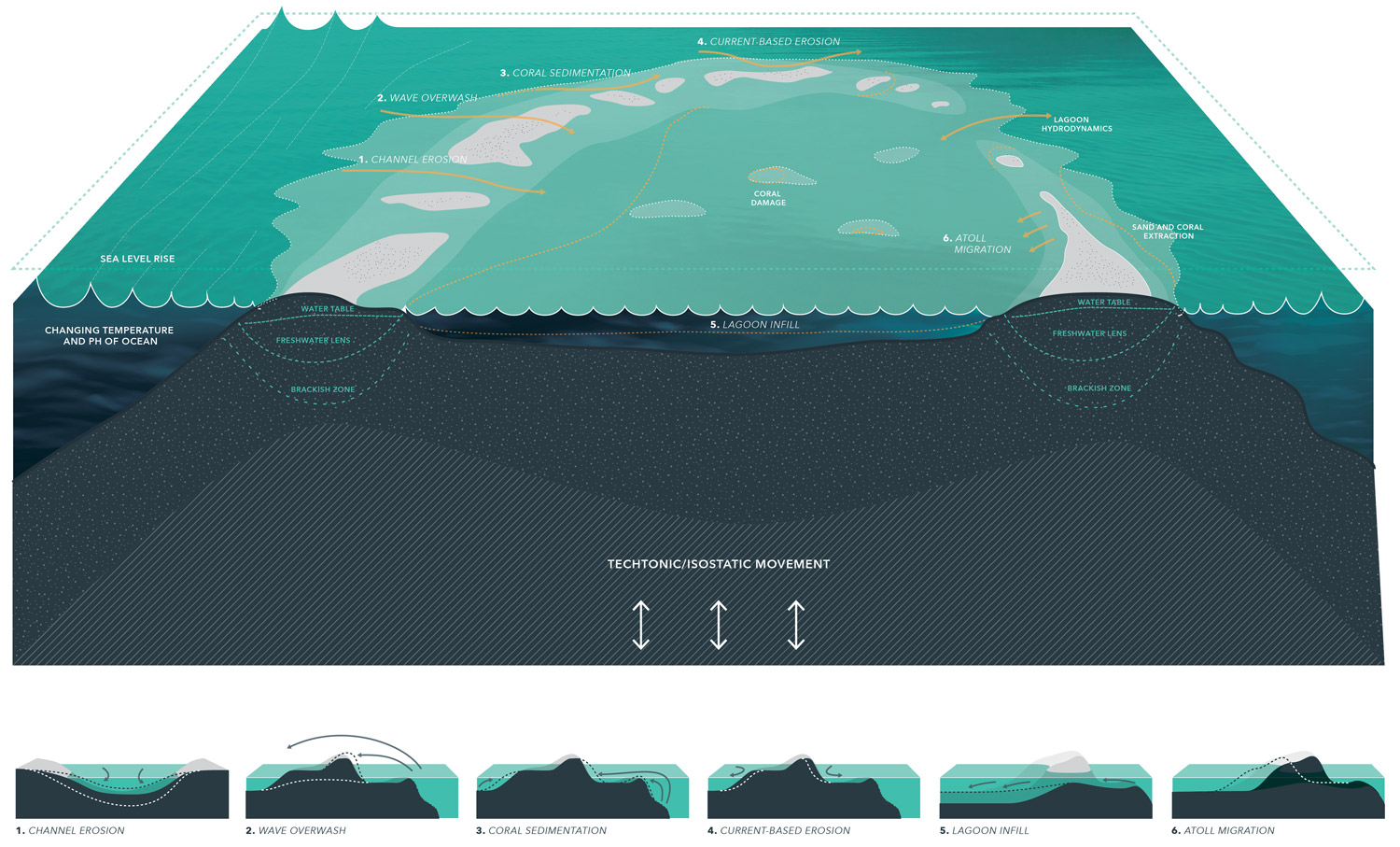

Atop these delicate structures, which evolve based on currents, storms, and sea level, resources are scarce and habitation is vulnerable to the whims of the sea. Cyclones can easily cause sea swells that inundate entire settlements. Atolls are highly vulnerable to climate change and sea level rise, but the issue is more complex than the “sinking islands” narrative suggests. Rather, atolls can (and throughout history have) grown upwards in response to sea level rise, as the coral reefs and that compose them grow towards the sun’s rays. During rapid ice melts following the last glacial maximum, atolls compensated for sea level rise at a rate of up to one meter [3 ft.]/century (similar to mid-range predictions for sea level rise today). However, this process makes the islands increasingly unstable as new coral sediment and foram sands are deposited, growing the islands. Furthermore, risks of ocean acidification and coral bleaching could kill off coral reefs and other calcareous species, halting this process altogether (Fig. 5).

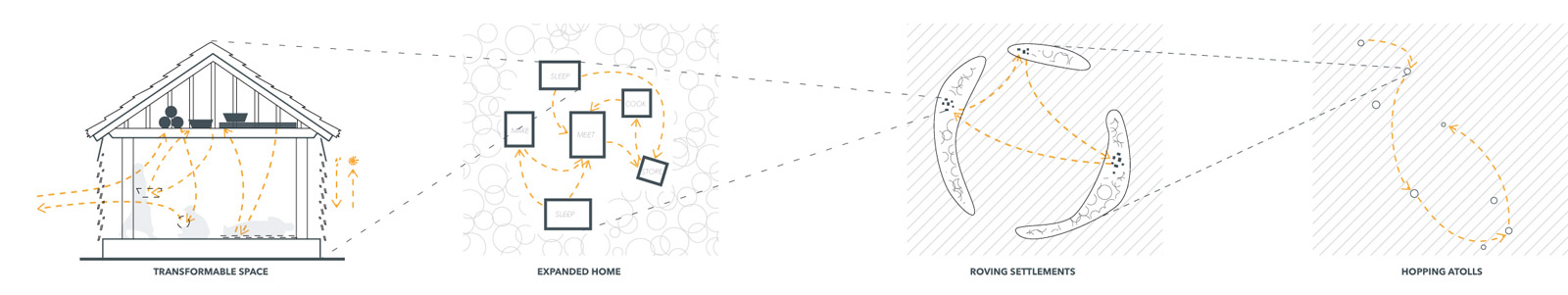

Atoll-dwellers have developed flexible models for inhabiting their fluid geographies.10 Traditional Tuvaluan architecture and settlements are characterized by transformability and mobility that allow their inhabitants to adapt to fragile atoll ecosystems. The traditional Tuvaluan house is a post and beam construction with a thatched roof and coral-rock foundation, ranging in size from 2,5x5 m [8x16 ft.] to 5x10 m [16x33 ft.]. The structures are built without walls to allow for through-breezes in the tropical climate, but woven coconut frond mats can be attached to the eaves to keep out rain during storms.11 Roofs were also demountable, and during violent cyclones could be removed and placed to the leeward side of the house for shelter.12 Master builders (tufuga fai fale) sometimes developed unique typologies, including the fale poutasi (post house) from the atoll of Niutao which was supported by a single central post and could be rotated to allow for maximum wind capture on hot days.13 One citizen observed, “We are like nomads... We don’t want to be enclosed in something.” 14 Flexible structures accommodated hot, dynamic tropical climates.

Prior to the influence of missionaries and colonists, settlements were organized around extended family clan compounds, with people moving between different function-specific structures (sleeping houses, cookhouses, storage structures) throughout the day. Not only were these hamlets loose aggregations that encouraged movement, but the settlements themselves were mobile, with families relocating to different sites around the lagoon “to allow the coconuts to grow up and to give the fishing grounds a rest.” 15 The “bush,” where coconuts, pandanus, and bananas were cultivated and collected, surrounded original hamlets. Beyond, the ocean and lagoon served as an extension of living space, used for bathing, recreation, and fishing. Settlements were sited based on access to fishing grounds, in areas protected from reef waves and wind (Fig. 6).16

This history of mobile adaptations extends to inter-atoll and cross-Pacific migrations/resettlements necessary for the very survival of atoll denizens:

In historic times atoll dwellers were extremely mobile and far from insular; men and women moved readily between islands in search of new land, disease-free sites, wives, trade goods, and so on. In this way some islands were populated, depopulated, and later repopulated. Mobility itself was responsible for demographic survival; without mobility, adaptation and change were impossible.17

The Tuvaluan community is very much defined by being “fluid, multiple and complex” 18 from the time of its original settlement, and this historical narrative extends into the present as Tuvaluans migrate following destructive cyclones, or in search of work, education, and opportunities. However, the mobility of all atoll-dwellers has been interrupted by colonial sedentarization, post-colonial nation-state boundaries, and nationalist politics. Though many Tuvaluans independently obtain work and education visas to migrate abroad (primarily to Fiji or New Zealand), the possibility of adaptation via migration for residents of independent atoll states has been severely restricted.

Similarly, Western building-models adopted in the colonial and post-colonial era lack sensitivity to local climatological conditions. Enclosed concrete block houses, which connote status due to their aesthetic of permanence, soak in the tropical sunlight all day and radiate heat through the home all night. Metal roofs similarly capture heat, though they have become increasingly essential for rainwater capture as freshwater lenses become contaminated. The destruction associated with Bebe, discussed above, as well as damage from more recent storms, can be in part attributed to the inappropriateness of cheap Western-style housing.

The “deterministic” view that Pacific Island nations “too small, too poor, and too isolated to develop any meaningful degree of autonomy” and as such require outside benefactors in order to adapt to risks is rejected by Oceanic scholars, in particular Epeli Hau’Ofa. The Tongan-Fijian writer and anthropologist emphasizes that prior to European intervention, the Oceanic “universe comprised not only land surfaces, but the surrounding ocean as far as they could traverse and exploit it, the underworld with its fire-controlling and earth-shaking denizens, and the heavens above with their hierarchies of powerful gods and named stars and constellations that people could count on to guide their ways across the seas.” Instead of “islands in a far sea,” Hau’Ofa proposes conceptualizing the Pacific as a “sea of islands;” a fluid space not bounded waters, but expanded by oceanic connections.19

FIXING THE EDGE

Atoll Interventions

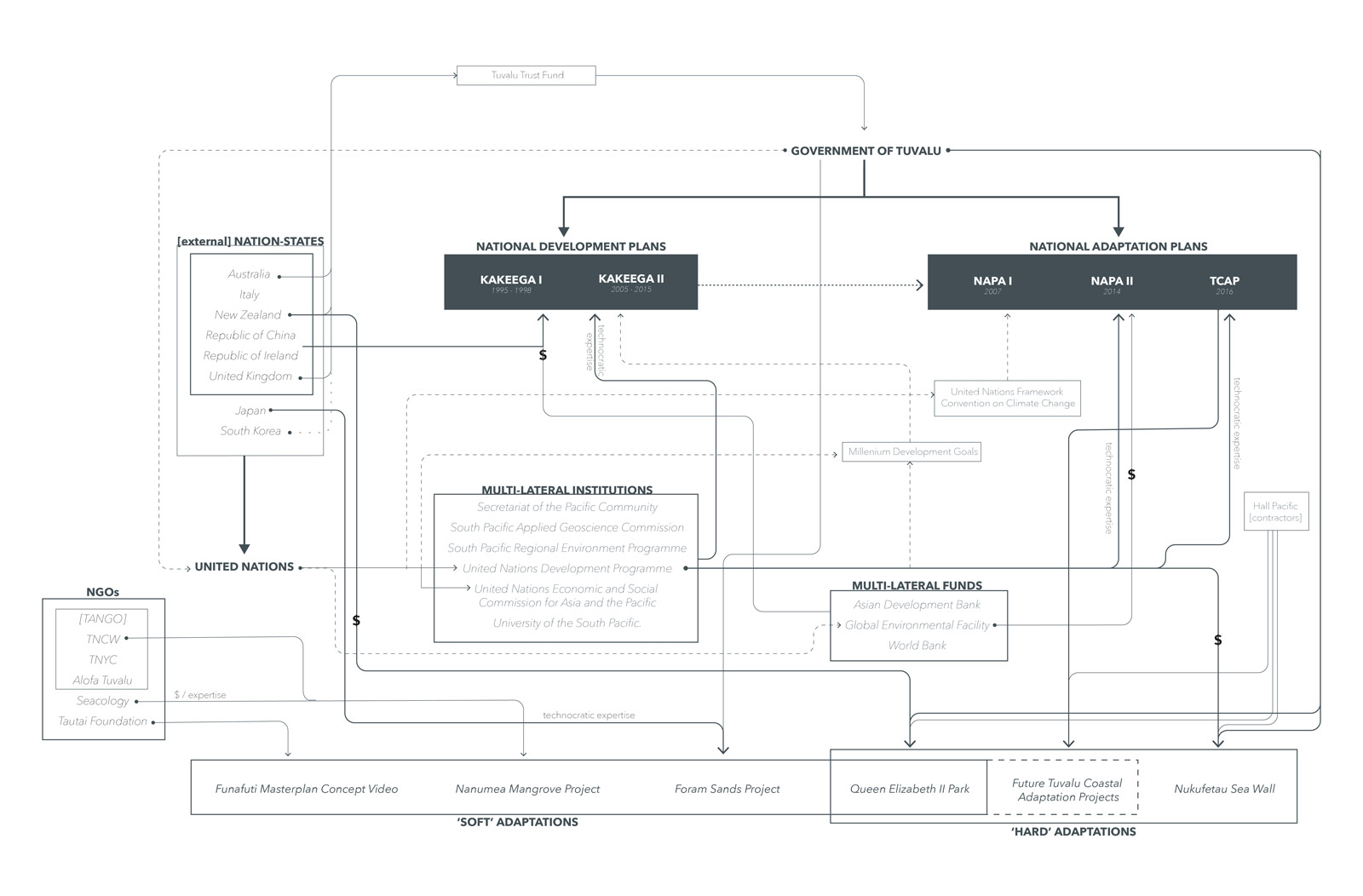

Tuvalu’s current processes for adapting to climate risk often do not allow space to address the archipelago’s fluid context. Tuvalu’s primary plan for dealing with climate change is the National Adaptation Programme(s) of Action (NAPA).20 The development and implementation of NAPA was led by the Government of Tuvalu, together with multilateral organizations and foreign consultants - namely Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) which provided technical support, and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which provided funding.21 Because of their participation as one of many island nations in the broader United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) climate adaptation program, Tuvalu’s adaptation plans look much like their island cohort’s, and even share similarities in structure and content with urban and national climate change adaptation plans from around the world. These multilateral systems attempt to normalize Tuvalu into standard development frameworks, failing to acknowledge the distinctly fluid nature of the nation’s components (Fig. 7).

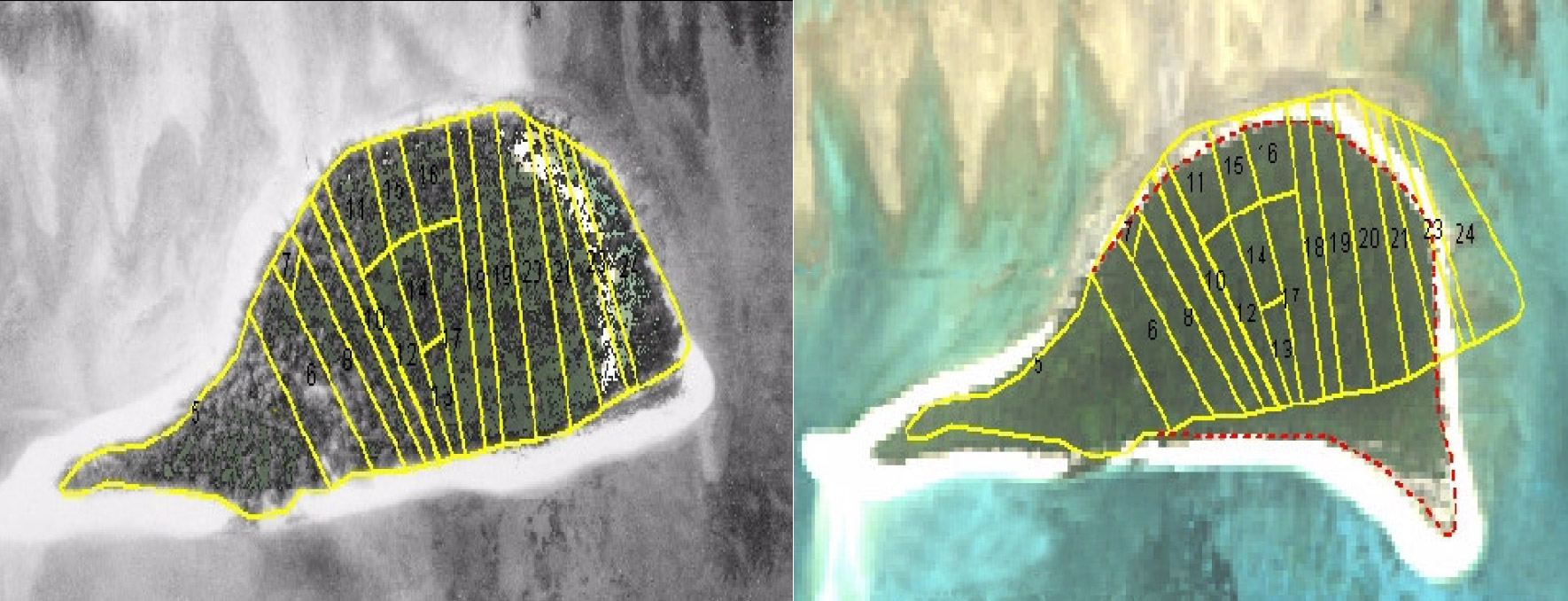

A lack of attenuation to the conditions of atoll flux is articulated with particular clarity in the NAPA I project document through the analysis of Fualefeke, an uninhabited islet on Funafuti atoll. Since 1984, the coastline of this islet has migrated such that two parcels were eliminated, and additional land was accumulated on the lagoon side of the inlet (a formation typical of spit-generation processes). This island migration is cited as evidence of risk through which “the stability of the marine and terrestrial ecosystems will also be adversely affected,” illustrating “coastal erosion and its cost on Tuvalu landowners and families.” 22 However, the document fails to acknowledge that this is perhaps more evidence of the problematics of Western property ownership structures overlaid on fluid islands rather than of climate risk.23 In fact, these processes are inherent to atoll marine and terrestrial geographies, directly contradicting high-ground logics where land is understood as a fixed and permanent commodity 24 (Fig. 8).

The living geographies of the Tuvaluan archipelago and associated cultures of mobile adaptation suggest that climate resiliency projects in this context should accommodate or even work with fluid atoll systems. However, adaptation through attempting to “fix” or “solidify” atoll perimeters emerged in the colonial era, and is an increasingly popular model as Tuvalu’s profile (and urgency) as a “sinking” nation grows.

Seawalls do not sit easily in this context of fluid geographies and mobile populations. The same NAPA document that chastises Fualefeke for its natural transformations is critical of hard-edge solutions to rising seas: “Sea walls cut off the landward supply of sand during storm events, resulting in waves attacking unprotected areas to a greater extent than they would have done prior to the sea wall construction.” The hard surfaces of smooth sea walls reflect waves back out to sea with little loss of energy, doubling wave heights as they meet incoming crests.25 The extracted material used to build seawalls, often sand or coral rock collected or dredged from surrounding waters, can further disrupt sedimentation/erosion processes.26 While seawalls attempt to solidify one portion of the edge, the introduction of hard infrastructure disrupts atoll hydrodynamics, often creating new problems elsewhere. For example, in Tarawa, the capital atoll of Kiribati, the introduction of a causeway is blamed for the erosion and eventual extinction of Bikenman islet across the lagoon.27 A harbor constructed in Vaitupu, Tuvalu in the 1990s caused erosion and worsened damaging waves.28 Similarly, a past seawall in Nukufetau, Tuvalu on one end of the island resulted in the complete erosion of the opposite.29 Seawalls not only disrupt sediment flows, causing shifts in erosion/accretion processes, and accelerate erosion around/behind/underneath the structures by speeding up the flow of water, but they also disrupt nutrient flows necessary for the survival of coral reefs. Given the essential role of corals in atoll construction, the starvation of reefs could be devastating.30 Writing about the use of seawalls by the US Army Corps of Engineers on American coastlines, Pilkey and Dixon note: “A heavy price is exacted for using engineering structures, however […] hard stabilization has proven to be irreversible.” 31 In the context of coral atolls, this may mean a permanent inhibition of an atoll’s capacity to self-adjust to rising seas. The introduction of hard edges amounts to the permanent creation of an iron (concrete) lung around the islands, with its life-essential ecosystem irrevocably disrupted.

In his book Seeing Like a State (1998), James Scott describes the reliance of modern government on systems for controlling, measuring, and regulating. In order for a state to understand, manage, and tax its territory, it must map a simplified version of it, lacking the rich socio-ecological complexity of reality. Scott uses as an analogy scientific forestry, which, though it creates a measurable and extractable system of production through monocultures, the model problematically eviscerates habitats and local economies which rely on forest products, and eventually makes the land unproductive through the clearance of underbrush and deadfalls which return nutrients to the forest floor.32 Similarly, attempting to fix the edge of a fluid atoll is associated with imposition of Western state-building worldviews in a dynamic Pacific Islands context. While dramatic interventions in Tuvalu will likely be necessitated by climate change, these should not emerge from a simplified, frozen conception of atolls and their denizens.

Seawalls, berms, and dykes are often part of the vocabulary of global “climate-proofing” plans, which self-advertise as “solutions” to climate change. Just as seawalls amplify erosion on other parts of a coastline, dykes and berms amplify flooding for those outside of the walls, and can sometimes worsen flooding inside due to the “bathtub” effect.33

Seeing Like a State and associated solutions-oriented mindsets may fail to account for the complex systemic outfalls of rigid interventions, creating new problems in the process. Timothy Morton describes climate change as a hyperobject,34 acting at a scale that can no longer be physically sensed by our bodies, or, borrowing from Levin et al., a “super wicked problem [...] a wicked problem for which time is running out, for which there is no central authority; those seeking the solution are also creating it, and policies discount the future irrationally.” 35 The conflation of solution and problem is perhaps illustrated by the Taborio-Ambo seawall, constructed as part of the World Bank and GEF funded Kiribati Adaptation Project II (KAP II), in Tarawa, which ultimately exacerbated erosion and exposed water infrastructure; KAP III is now working to address this new problem. One is reminded of Ulrich Beck’s notion of “reflexive modernity,” where society is constantly mediating risks of our own creation.36

This “super wicked” framing of climate change cautions against path-dependent trajectories that lock-in approaches that cannot successfully cope with the uncertainties associated with global climate risk.37 In this context, drawing on Amory Lovin’s seminal framing of “soft” vs. “hard” paths for energy production, it is useful to consider approaches to climate adaptation also in terms of both “hard” paths (heavy, inflexible, and expensive technocratic solutions) and “soft” paths (lightweight, ecological, adaptive and bottom-up approaches).38 By framing current approaches to climate adaptation in Tuvalu through this lens, this paper seeks to explore the limitations of various approaches for securing Tuvalu’s fluid edges, as well as the climate change imaginaries (or “riskscapes” 39) associated with different interventions.

Hard Solutions

Even prior to concerns about global warming-related sea level rise in Tuvalu, twentieth-century British colonists began to introduce seawalls as part of their toolkit for managing the atoll archipelago (at that time governed alongside Kiribati as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony). Walls were used to expand space for agriculture, particularly copra, or dried coconut flesh, which was “the staple product of the South Sea Islands” according to a 1920 account.40 By the 1960s, land reclaimed using seawalls on Maiana in the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati) for copra production prior to World War II had “gradually reverted to bare salt flats” 41 and housing built on the reclaimed land had to be abandoned. The agricultural report goes on to note that “tidal canals are constantly moving material by scouring and depositing elsewhere”; 42 attempts to fix ground were being negated by the atoll’s fluid geography. However, the resident colonial land use officer saw this simply as a technical failure, and in his recommendations proposed to re-reclaim the land using sturdier walls.43 Remnants of failed seawalls litter the coastlines of the former Colony.44

The almost comedic failures of a midcentury seawall project on Nanumanga atoll, Tuvalu suggest a similar lack of contextual understanding. Following a 1949 analysis on the practicability of a concrete seawall (a similar proposal for Nanumea was found infeasible) to protect agricultural space, 243 bags of cement were shipped, but the vessel ran aground in Nanumea, and only half of the cement (110 bags) was able to be salvaged. The salvaged bags, stored under canvas and thatch, were largely destroyed by heat and humidity waiting for transfer to Nanumanga (a small amount was appropriated for local construction). The 257 bags that were never shipped from Tarawa (now the capital of Kiribati) due to inadequate boats were similarly lost. A 1954 analysis wrote off the entire project, noting that: “the construction of a wall is unlikely to prevent seepage of saltwater into garden pits which was the original aim of the scheme.” 45 Both materials and methods of the colonial authorities failed to “understand islands in their own terms.” 46

Not only did the colonists “see like a state,” but they also saw specifically like a Western high-ground, colonial, “fixity-oriented” state non-acclimated to dynamic coral atolls and Tuvaluan spatial practices. This is also visible in other forms of paternalist management undertaken by the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Authority, and prior to that, missionaries in positions of power. Early Samoan pastors encouraged a shift into a village structure, which allowed them to keep a closer watch over the inhabitants and encouraged the destruction of existing buildings and rebuilding of Samoan style architecture with raised platforms.47 A rule was introduced banning travel from one island in the archipelago to another; abruptly, Tuvaluan society transformed from mobile to fixed. Colonial projects in the Pacific with benevolent intentions sometimes attempted to encode cultural systems into Western laws; for example, in Fiji clan (maataqli) lands were carefully mapped and measured in part to prevent their appropriation by European capitalists (a Gilbert and Ellice Islands Native Lands Act similarly prevented the sale of “native” lands). However, in doing so, they fixed in place a system, which traditionally evolved dynamically as a process of negotiation - as maataqli expanded or contracted, or as the productivity of landscapes shifted, these clan boundaries had been redrawn. The paralysis of property lines meant that even if a family line died off, or if a meadow became a swamp, parcels could not be adjusted to accommodate these changes. As rising seas threaten coastal perimeters, this lack of negotiability will become problematic for low-lying maataqli needing to migrate upwards as sea levels rise.

The managerial colonial ethos tended to create a cycle of solving problems of their own making. A component of this “reflexive modernity” is described at length in a 1967 colonial report on health and water:

It is rather surprising that the atoll populations, numbering nearly 90,000 in the Pacific region, have lived for centuries without realizing they have water supply problems. They cleaned their fish in the sea, boiled their taro and breadfruit in brackish water, and bathed in the sea. They wrapped their fish with leaves and cooked it in a heated coral oven, without making use of any water. They put their food on leaves and ate with their fingers, which they can wash in the sea. To quench their thirst they chewed pandanus fruits or drank coconuts, but more often, they made do with very brackish water from wells. They did not have to wash their simple garments made of locally available materials, but always replaced them with new ones. When rain came they took their natural shower and drank some freshwater for a change. 48

Based on the description above, there was no historic water problem. Rather, water as a resource was conserved based on the scarcity of supplies; the necessity of laundry was only created by the introduction of Western garments. Similarly, when colonial schools were seen to erode indigenous traditions, a “Vernacular Education Committee” was formed to reintroduce traditional stories and practices.49 When the banning of traditional population control (i.e. infanticide) produced overpopulation, resettlement schemes including sites in the previously unpopulated Phoenix Islands chain were implemented. These settlements met their own complications and largely failed.50

Contemporary solutions for atoll edges may similarly be seen in the light of this reflexive framework. As we saw on Fualefeke, the application of rigid private property boundaries on fluid atoll geographies politicizes natural coastal fluctuations. Similarly, the construction of permanent, expensive (and often donated) architecture and infrastructure near-shore necessitates coastal fortification; seawalls are built to protect these investments. Below, we examine three recent “hard” coastal infrastructure projects in Tuvalu; notable not only for their attempts to “fix” a fluid edge, but also for the role of competing “resilience imaginaries” of the actors involved in the creation of these projects.

In Nukufetau, a three m [9.8 ft.] tall, 500 m [1,640 ft.] long seawall was constructed in 2016 as part of the NAPA I project, implemented as a partnership between the Tuvaluan government and UNDP with financing from GEF Least Developed Country Fund (LDCF) (Fig. 9). The seawall, made of sand packed in geomembrane bags replaced an older, crumbling seawall made of concrete blocks. The technical assessment, consultation, design, and construction process took place over several years. As part of the technical assessment process, various designs were identified including nature-based solutions. Proposed design options were developed by an international consultant, who traveled for ten hours by ship to the atoll and was able to complete a site analysis within the few hours before the ship returned to Funafuti. This sort of extreme time and travel constraint is a common challenge that foreign development efforts face when engaging external experts for technical design and community engagement in remote communities. Follow-up consultation processes with the Nukufetau kaupule (village council) and residents resulted in a rejection of the nature-based designs, based on perceptions that these solutions might not be able to withstand and protect them from strong waves. The community instead requested a “hard,” structure-based solution to provide the sense of security they sought from a seawall.51 This sentiment grew stronger after residents experienced the strong storm surges that swept across the islands during Cyclone Pam. The final geomembrane bag seawall design emerged as a result of mediation between being “hard enough” to provide the sense of security the islanders desired and being simple, modular, and transportable enough so that it was physically possible to construct in a place only accessible by sea.52

Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP), a US$36 million project financed by the Green Climate Fund (GCF), aims to scale Nukufetau’s example of fixing an edge, fortifying a larger portion of Tuvalu’s coast.

The project plans to increase protection works from around 570 linear m [1,870 ft.] of coverage currently to 2.780 m [9,121 ft.] at completion, across three different islands.53 Given the large scale of the initiative, both financially and geographically, the Tuvalu Government and UNDP aim to capture and integrate the lessons learned from previous coastal protection efforts by applying a range of measures - including ecosystem-based initiatives, as well as geo-textile and rock revetments.54 However, the funding proposal for the project only accounts in its intervention list (and pricing) for rigid measures and beach nourishment, largely influenced by the Fund’s project templates that reflect organizational funding strategies and priorities. However, in the proposal descriptions, the importance of soft measures is incorporated. For the Funafuti project, the document also states that “a combination of rock armor revetment and pre-cast concrete revetment options is considered most cost-effective” which can be “complemented” by “softer” options.55 A large focus of the initiative will also entail development of a cohort of local experts in Tuvalu who can lead a more participatory community consultation as well as technical design process that focuses on both awareness raising and more meaningful dialogue, consensus building, and participation over a longer period.

While speaking towards soft-interventions and participatory processes, this large-scale climate adaptation project is still largely anchored around fixed-edge solutions. With this funding, Tuvalu and its benefactors have an opportunity to reframe coastal intervention approaches, going beyond tokenistic participation and considering alternative strategies that work with the human and ecological systems of the atolls long-term. However, project leaders and stakeholders would require tremendous commitment and courage to challenge norms and to carry this out. The training of “local experts” could well serve this end; however, this would likely require transcending the Western-style training they will receive.

Soft Approaches

A critical approach to adaptation in the context of the atoll archipelago would explore alternative soft-edge strategies drawing on the existing knowledge and ecologies of Tuvalu’s atoll systems. However, former “soft” solutions have had their own set of limitations induced by techno-scientific approaches, lack of visibility, lack of context-specificity, and slow pace.

With the commonly cited assumption that Tuvalu may become uninhabitable as soon as the next 25-50 years (though futurology in this context is widely uncertain) speed is clearly an important characteristic in adaptation planning; likewise, relying on foreign aid, projects which a donor cannot easily point to in a photo may lack incentives for funding.

Queen Elizabeth II Park, framed as a beach nourishment project on Funafuti’s lagoon, can be seen as a combination of hard and soft. It is termed by the project contractors (Hall Pacific, also engineers of the Nukufetau seawall) as a “reclamation” project, emphasizing the new 40.000 m2 [430,556 sq. ft.] space it will create - suggesting it may serve as a model for possible future land reclamation to accommodate the capital’s expanding population. The contractors also emphasize the rocky (rather than sandy) nature of Funafuti’s lagoon coast; though scientific research suggests that this is the result of a causeway constructed between two islets on the atoll, which has cut off sediment flows along the foreshore.56 This reclamation has been achieved by dredging 115.000 m3 [150,414 cu. yd.] of sand and limestone from the atoll’s lagoon, likely disturbing corals and sedimentation regimes. The new land is retained by “two strategically placed groins made out of 2,5 m3 [88 cu. ft.] sand containers.” 57 Google earth photos show that the beach has already migrated significantly since its April 2016 completion. Less than a year later, at a February 2017 meeting regarding the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project, the park is already described as “highly eroded” and mitigation efforts are requested.58 So while this intervention is “soft” in that it is primarily constructed from sand and gravel, the anticipation of fixity suggests the project’s interface with larger atoll systems was underdeveloped.

Another primary “soft” approach on Tuvalu has been led by Japanese scientist Hajime Kayanne, through a process he terms “geo-ecological” 59 or “eco-technological” management.60 Borrowing Sovacool’s definition of “soft” adaptation paths, it is worth noting that while materially soft, the project lacks a community-driven, bottom-up approach.61 Drawing on the ecological and geomorphological processes that drive atoll formation and growth, the project works to amplify lagoon production of foraminifera, small star-shaped protozoa whose shells produce foram sand, which with coral rubble form the primary sediment components of coral atolls. By incubating foraminifera production, the project seeks to increase lagoon sediment, growing a natural beach-nourishment system.62 The team’s research also highlights how current hard edge interventions, such as the causeway connecting two islets at the southern tip of Funafuti atoll (Fig. 10), has starved the capital’s lagoon beaches, causing erosion now typically attributed to climate change.63 This “Eco-technical Management of Tuvalu against Sea Level Rise” was a five-year research project initiated in 2008 supported by Japan’s Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) program, a Japanese government program that promotes international joint research.64 A pilot site for foraminifera propagation has been sited along Funafuti’s lagoon, and tank-grown forams have been planted onto mats and inserted along the beach. While the early tests have been successful from a scientific perspective, the plan met resistance from the community, who perceived the scope of the intervention as too limited and slow relative to the large and urgent risks they face. The project perhaps saw the island’s ecology “on its own terms” 65 but failed to understand the community in which it was engaged.

It is also worth acknowledging Japan’s own interest in atoll growing. Okinotorishima is a submerged reef island claimed by Japan with only two small rocks that peek above sea level at high tide. Closer to Guam than to mainland Japan, their claim to Okinotori allocates a huge oceanic territory per the 1982 UNCLOS discussed above.66 However, their claims to the island and associated seas have been threatened by Chinese contestations over whether the rocks fit the UN’s definition of islands: according to UNCLOS, “Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone.” 67 Furthermore, sea level rise and erosion threaten the two existing above-water rocks. In response, Japan has sought to both call into question the definition of rocks (as compared to reefs), erecting structures to protect the rocks, and incubating transplanted corals and foraminifera with the goal of accreting bona-fide islands.68

Around the world, spin-off reef-growing technology companies have become their own start-up niche. Kayanne’s research spans to Okinotori as well, and he is quoted as saying: “Right now, no one can live on Okinotori... But we have examples around the world where people live on atolls made of coral gravel. We know it can happen. Island formation is possible well within a human generation.” 69 While having additional motivations does not preclude doing effective and locally sensitive work in Tuvalu, it does suggest that coral- and foraminifera-growing science there may be an incubation for projects with national-scale Japanese interest. Given the contested territorial claims currently being ignited in the South China seas, the ability to grow national territory could become a hot commodity.

Other “soft” strategies in Tuvalu include the mangrove nursery developed on Nanumea atoll in 2008, sponsored by the California-based nonprofit Seacology in collaboration with the Tuvalu National Council of Women. Mangrove rehabilitation is a common tool in green or ecosystem-based adaptation projects, and in this project, a kilometer-long [0.6 mi.] planting was intended to curb erosion and buffer the primary settlement against storms.70 However, in spite of multiple re-plantings, the seedlings were continuously washed away by storms and high tides.71 While the Seacology website notes some difficulties with the plantings, its ultimate failure is not acknowledged online - perhaps calling into question the long-term impacts of other projects listed on their website. Photos of the mangrove project are often used in more optimistic portraits of Tuvalu’s risk and resilience, while without a personal connection to Tuvalu it takes significant digging to find documentation of the project’s failure. Of course, like larger-scale aid-projects, Seacology relies on the image of the work, presented to donors for funding. Other mangrove-planting projects, including those planted in Niuatao and Nukulaelae as part of the NAPA I project, were similarly washed away.

Historic evidence shows that in past eras of sea level rise, mangroves have migrated inward, suggesting that while they provide an important buffer against wind, waves and erosion, their capacity to mediate against higher seas may be limited.72 Planting schemes must accommodate space for migration if mangrove projects are to have long-term impact. Coastal scientist Bregje van Wesenbeeck suggests that many well-meaning mangrove projects can ultimately be maladaptive, disturbing ecosystems and wasting community resources with projects that will ultimately fail as a result of monoculture planting, use of inappropriate species, and/or improper site selection. This helps to explain the high rate of failure of mangrove-planting projects; in the Philippines, the long-term survival of rehabilitated mangrove forests was found to be only 10-20%. The report authors further note that monitoring of mangrove planting projects is often poor, and few project documents identify survival rates.73

RISKSCAPES AND (RE)FRAMINGS: IMAGINARIES OF RESILIENCE

Aid/Development Riskscapes

With a limited local economy, Tuvalu must look outside its boundaries to fund adaptation initiatives of any significant cost. Donor-funded organizations have multiple motivations: creating a successful project for their beneficiaries; capturing the image of a successful project to deliver to donors and taxpayers evidence of impact and sustainability; and securing future projects to scale successful results. As with the mangroves above, a project with a successful image may not be an effective intervention in the long-term. A focus on creating many projects across the globe results in a technical approach, and “donors frequently construct discourses of capacity in terms of technical and socio-cultural deficiencies able to be remedied.” 74 Standards about what constitutes a “resilient” space likely come from Western or “universal” imaginaries, and solutions similarly will come from an accepted toolkit of approaches. These “portable solutions” supplied by mobile experts are part of an ethos emerging from the Cold War era’s technopolitics, which prioritized the global expert over “place-based knowledge.” 75 Even if community participation is typically one of those tools, its buzzword-ization has reduced its legitimate use. Leal notes that: “Reduced to a series of methodological packages and techniques, participation would slowly lose its philosophical and ideological meaning.” 76

Thus, the aid organizations and foreign technical experts play a primary role in defining the scope of both problem and intervention. Coming from high-ground nations, these technocrats are likely to see fluid edges as a problem, and fixed perimeters as a solution.

Aid organizations and its donor agencies must also consider their own reputations and survival. Projects with visual products and tangible solutions that can occupy glossy brochures help to communicate and illustrate “development,” “climate change,” and “adaptation” in a simple way, putting a face to the familiar story portrayed by the media. Rather than contesting this “fetishization,” compliance is desirable for all parties as it can secure further funding. Furthermore, “saving” a “sinking” island nation brings additional prestige. Bilateral, multilateral, and regional organizations compete for projects and sometimes donors, often leading to poor coordination across multiple projects. Donors also often bring with them their own agendas, and recipients who lack leverage become “policy-takers.” 77 The seawalls in Tuvalu are constructed by this complex interplay of imaginaries, riskscapes, development finance, media, and politics at various levels, rather than being based wholly upon local needs and desires.

Researcher/Scientist Riskscapes

Tuvalu’s dramatic climate risk makes it a popular research site, as attested by its selection as a case by the authors.78 As well as for donors, incentives for scientists or other types of researchers choosing to work in a particular site may be multiple. The imaginary of Tuvalu as a “sinking” island may help researchers secure grants as they engage with the “front lines of climate change.” We have also seen that a site like Tuvalu might be seen as a lab, developing science and technology with applications elsewhere, of national interest to other states. Researchers are also likely to visualize risk primarily within their disciplinary boundaries; an environmental scientist will likely be preoccupied with the physical conditions of sea level rise, coral reefs, temperatures, or ecosystems, while a social scientist will be more concerned with human factors such as housing quality, health, and cultural practices. This is visible in the foraminifera project, which although it was technically, academically, and internationally successful, it was not perceived or experienced as such by many locals. Similarly, a much-cited paper by Webb and Kench documents an average overall increase in area in atolls over recent decades, suggesting that sea level rise perhaps will not inundate atolls79 - prompting a slew of news articles with titles like “Shape-shifting islands defy sea-level rise” 80 and “Not So Much Trouble in Paradise: Are Coral Islands Really Doomed?” 81 Acknowledging that “Persistence of reef islands does not necessarily equate to geomorphic stability,” 82 it is outside the scope of their research to address whether and how an increasingly dynamic atoll might be inhabited, and what this fluctuating condition means for current adaptation approaches. An increasing trend towards commercializing climate science further blurs the incentive structure for providing equitable, locally specific adaptation.83

Tuvaluan Riskscapes

Tuvaluan imaginaries of climate risk and adaptation are likely the most complex. On the ground, short-term concerns surrounding overpopulation, resource scarcity, freshwater supplies and waste disposal can be seen as more urgent than long-term climate risk,84 although the flooding associated with Cyclone Pam in 2015 heightened climate change sensitivity for many. Religion also plays a role in shaping riskscapes, and until recently, the Christian narrative of Noah’s flood prevented many from seeing future inundation as a possibility. As suggested by Nunn, remote Pacific Island communities may seek to emulate solutions that have been successful elsewhere including seawalls and land reclamation. While being interviewed, Funafuti residents often cited island-building projects in Dubai as a precedent for reclaiming ground in the atoll’s lagoon.85

Some researchers have argued that for politicians and other leaders, aid-related projects are not a distraction, but rather a primary economy:86 a form of “microstatecraft” where tiny nations like Tuvalu leverage their international position as an independent, yet threatened state. As of the 2007 census, 40% of employed Tuvaluans held government jobs; beauracracy forms an important part of the Tuvaluan economy. On a global stage, atoll nations have further “capitalized on their victim status” as “canaries in the coalmine” 87 to attempt to influence global climate policies and agreements, to at least partial success. However, as Farbotko crucially observes, the canary must die in order to fulfil its role as warning signal.88

The primacy of the aid/development regime in Tuvaluan climate-change adaptation has left little room for bottom-up local models to develop, in spite of the deep local knowledge surrounding the inhabitation of fluid, resource-scarce atolls. Tuvaluan and Pacific researchers suggest that perhaps instead of portable technical experts bringing their models to the islands, they should instead learn from indigenous knowledge for inhibiting environmental uncertainty:

Pacific Islanders have extensive experience living in these small and isolated islands for generations and have formulated worthwhile local survival knowledge, skills and practices that offer useful lessons to contemporary societies on how to address climate change and sea level rise.89

Interest is emerging surrounding the role that indigenous and place-based knowledge might play in climate adaptation; living in close relationships with their environments, these communities are often more closely attuned to adapting with conditions of climatic flux. Customary, cyclical practices regarding resource use and protection has helped groups such as the Miriwoong in Australia respond to fluctuations in resource availability and protect from over-extraction.90 Similarly, in Tuvalu, fish stocks were traditionally protected by various prohibitions and tool restrictions, and important tree species had a protected status. Learning from adaptive indigenous knowledge in Tuvalu might mean drawing upon housing, settlement and migration vernaculars that accommodate atoll dynamism over time. As the world faces a wetter, more uncertain future, inhabitation of flux will become an increasingly valuable skill.

Contested Resilience?

These various stakeholders are not only motivated by different considerations, but also potentially by different timescales that shape perceptions of appropriate proposals. Tuvaluan politicians may be motivated by timescales associated with election cycles; international agencies with targets and timelines set forth by global climate change treaties; donor governments by timescales associated with moving forward international political agendas; NGOs or multilaterals by project timelines; and everyday citizens by both immediate risks and long-term concerns about the future of their families and communities. Researchers may be interested in short-term study results and/or long-term research implications (or longer phase studies). While a seawall may help buffer against erosion or flooding in the short term, in the long term it is likely to exacerbate erosion elsewhere. Furthermore, hard infrastructure requires costly ongoing repair and maintenance: Nunn observes that “the cost of maintaining such structures is often beyond the means of such countries, so they often fall into disrepair and their original function is thereby negated,” ultimately resulting in a maladaptation.91 As the Tautai Foundation (based in Tuvalu) puts it, “when humans alter [atoll] systems they can quite literally pass the job of maintenance out of the hands of nature (who does it for free) and into their own hands.” 92 This is a long-term consideration that some groups may put off to be addressed by someone else in the future. Similarly, geographic scopes may vary as well; while a homeowner may prioritize the protection of their dwelling, others may define the problem relative to the scale of the settlement or entire atoll. The “canary” politics of the Tuvaluan prime minister suggest that not only the entire nation, but (perhaps circumstantially) also the denizens of all low-lying climate-threatened geographies, may fall into his sphere of engagement.

ALTER-ADAPTATIONS/POLITICIZED EDGES

What type of climate change adaptations might be appropriate in the context of any site is not merely a technical question, but also a political one. Blok, in his dissection of the urban riskscape assemblage in Surat, India, shows how those engaged in resiliency projects in the city frame urban risks relative to their own worldviews or agendas. The relationship between technocracy and democracy is called into question. He also emphasizes that contestation over various approaches may arise not only as a result of varying interests, but also as a result of varying ways of knowing, understanding, and seeing the world.93 Through its “fetishization” in the spheres of media and politics, climate change becomes depoliticized, “placing Nature outside the political, that is outside the field of public dispute, contestation, and disagreement” in the words of Swyngedow.94 Climate change is accepted as a technical problem, and for the liberal-leaning public, climate change projections and “climate-proof” solutions are generally accepted as universals. Relegating climate change adaptation to a technical sphere disallows radical reconceptions of what climate change might mean for our society, and obscures the worldviews and riskscapes of those on the ground.

Many motivations and perceptions make fixed edge solutions such as seawalls an attractive solution for Tuvaluan stakeholders. More importantly, they are highly visible, representing a concerted action against rising seas - significant for organizations and politicians with responsibilities to justify and/or explain clearly their actions to their voters and taxpayers, and seek funding and re-election (or future projects). This may also be important for local residents, as with those in Nukufetau, who would like hard and immediate physical evidence of their protection against cyclones and floods rather than a softer, nature-based solution. Infrastructural solutions may be perceived as faster than natural ones. Hard solutions may also help atoll dwellers embody global aspirations, aligning Tuvalu’s atolls with Dubai’s designer islands. Fixing the edges of atolls also aligns them better with fixed notions of property, housing, and infrastructure by reframing ground as a permanent commodity rather than a transient medium. Tuvalu suffers from a fetishized climate-changed image: its visibility on a global stage comes almost exclusively from media portrayals as “sinking islands;” nations “in danger of disappearing” entirely. This narrative of catastrophe too may shape the toolkit of perceived available strategies - if you are constantly being told you are about to drown, fortification may seem like the only solution. These different motivations for hardening atoll edges can be seen as part of different imaginaries of resilience: collections of ideas and practices surrounding what constitutes a secure and hopeful future for atoll-dwellers. What constitutes resilience will not be the same for all groups, or over all time/spatial scales.

Various proposals for counterplans and alter-atoll-adaptations may provide alternative frames for understanding Tuvalu’s climate risk and resilience. For example, the NGO Tautai Foundation, which provides a critical take on coastal engineering projects underway on the islands, produced in 2013 an unsolicited, locally developed “Funafuti Masterplan Concept Video” 95 (Fig. 11) including proposals for a porous breakwater system, a sewerage overhaul, and a halt to infrastructure works that fail to analyze impacts on atoll systems.

The foundation, which is led by a European woman who has been living in Tuvalu for many years, proposes comprehensive development of simulation models of coastal processes and wave climates to better understand how interventions will impact the atolls 96 as well as “natural resilience” and “augmented resilience” strategies that work with dynamic atoll systems, reminding us that “atolls are different!” than continental geographies.97 This proposal is developed over time through iterative analysis of local context and technical solutions rather than developed for a specific donor-funded “project.” While these propositions have not manifested in any large-scale works yet, as suggested in the Masterplan Concept, the foundation does work as a consultant on other projects, and the work is important in providing the conceptual framework for an alternative approach.

The award-winning “Borrow Pits Remediation Project,” funded by NZ Aid, also contrasts the normalized edge-fortification approach. The “borrow pits” on Funafuti are a series of large holes dug by the U.S. Army on Funafuti to construct the airstrip during WWII, when Tuvalu was still part of a British colony. Filled with polluted and stagnant water, these were considered a health hazard and associated pollution contaminated the island’s freshwater lens and exacerbated degradation of coral health. Migrants from outer islands built informal housing around the pits, and children swam in the stagnant pools. Tuvalu had previously sought donor funding from the U.S. to fill the pits, suggesting that this is a locally-originating project, rather than a solution handed down by an aid agency.98 By working to restore a disrupted geography (albeit with material dredged from the lagoon), this project created much-needed ground without disrupting coastal edges, while also solving a long-term health risk.

In Kiribati, Tuvalu’s Micronesian cousin to the north composed of thirty-three coral atolls, several projects are worth consideration. Kiribati’s emphasis on “migration as adaptation” is part of a national policy that emphasizes training and preparing citizens for future migration. Former President Anote Tong has prioritized planning for the future inhabitability of the islands, purchasing land in Fiji towards that end. These preparations toward migration counter the prevailing resiliency discourses, which emphasize staying put and adapting.99 At US$8.77 million,100 this purchase hedges against radically uncertain futures at a fraction of the cost of the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project. To further facilitate the self-directed migration of i-Kiribati to other countries, President Tong sought partnerships with countries where trainees could fill positions made available by aging populations.101

As a bottom-up model which stems from indigenous knowledge, the village of Aonobuaka on Abaiang atoll has come together to ban the use of seawalls, choosing rather to use the te buibui technique which uses woven fences built of local, porous materials such as fronds and branches to capture sediment and rebuild coastal beaches. Buibui are also incorporated as a “soft coastal protection measure” in the Kiribati National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plan 2016-2020.102 Instead of being imposed by an outside group or individual leader, the decision by Aonobuaka to forgo hard fortifications in favor of this traditional method was made collectively by the community.103 This was the result of a process by the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme with funding from USAID, to facilitate a “whole-of-island integrated approach to climate change adaptation” 104 which emphasized training local community members, and bringing the entire community (including women) together to identify problems and solutions.105 The role of experts in this case was to build local capacity and empower/support locally-determined adaptations. Global climate change finance timescales do not provide sufficient time for similar processes, which emphasize local leadership; while lengthier in the context of the urgent crisis of climate change, the importance of developing projects that work with the community and the geography cannot be understated.

Okinotorishima’s island-growing project described above provides a case for geopolitical framings surrounding atoll resilience in its attempt to grow a “rock” into an “island.” The survival of an atoll may be important as not only habitable ground and culturally significant space, but also as a lever for national sovereignty. As Tuvalu’s atolls are threatened with submersion and an associated loss of oceanic territory through UNCLOS regulations, alternative approaches to defining and capturing land with an eye to territorial ramifications may be required.

Re-Imagining the Edge

By unpacking edge-hardening approaches for keeping Tuvalu “afloat” in face of climate change, we strive to understand why hard solutions such as seawalls continue to be adopted as climate adaptation solutions despite various, well-known challenges, especially in the context of unique Pacific atoll geographies. Limited and simplified representations of atoll communities and systems can result in approaches which fail to negotiate the levels of complexity inherent to the islands. Competing riskscapes and resilience imaginaries further impact the toolkit of approaches perceived as available. Critical adaptive methods should seek to understand this complexity and these worldviews, placing adaptive options into the sphere of debate. In the context of Tuvalu’s fluid atolls, we advocate for reimagining the notion of an edge by expanding associated edge imaginaries. Resilient atoll edges cannot derive from continental technical toolkits alone.

In this exploration, we seek to not only critically reframe adaptation in Tuvalu, but also suggest broader re-conceptions of static “climate-proofing” and “solution-oriented” approaches to climate change adaptation. The lock-in of rigid approaches can be particularly inappropriate for the unique contexts of small island states such as Tuvalu. As designer/planners, we are particularly interested in how this limited conception of resilience within our disciplines influences the way we shape our physical and social environments. When design conversations become increasingly insular, or focus on best-practice solutions, we actively depoliticize our work in the built environment, seeking refuge in technocratic discourse - even while celebrating apparently radical frameworks including landscape or ecological urbanism. As de Block notes: “Although current rhetoric formulates an urbanism ‘against’ engineering, one could state [ecological urbanism] is even closer to what is narrowly defined as technocratic, problem-solving engineering projects.” 106 We can see this in the proliferation of berms, dikes and walls (often decorated in green) in the creation of “resilient” coastal cities. Like Tuvalu’s seawalls, which disrupt atoll systems and exacerbate erosion elsewhere, dikes protect flooding in one zone while amplifying water levels outside of their perimeter. Current development models for climate change adaptation which revolve around problem-solving best practices are problematic not only in their lack of cognition of the politicized sphere in which they operate, but also for the application of one-size fits all framings of issues and strategies to address them. Rigid “portable solutions” are particularly inappropriate in the realm of complex and entirely new problems, not to mention the diversity of cultural and social contexts in which these models are applied. Notably, the single-minded focus on fortifying the Tuvaluan coast eclipses the possibility of projects that hedge against future displacement, through land purchases, political agreements, or diasporic architectures. For the Tuvaluan diaspora in New Zealand, which hosts half of the population of the archipelago,107 many would like to see the vast funds being directed towards coastal “resilience” redirected to planning atoll communities in greater Auckland.108 The “conspicuous sustainability” 109 (or conspicuous resilience) of the seawall perhaps supersedes this sort of ex-situ alter-adaptation.

While atolls are in an accelerated state of flux, all landscapes are migratory. Instead of treating Tuvalu as a repository for high-ground adaptation models, we suggest that others seeking to adapt their cities and settlements might do better to learn from the extreme interconnectedness these geographies and communities illustrate. Approaches to climate adaptation must recognize and negotiate the various values, motivations, and riskscapes at play. We seek here to open up the conversation on climate adaptation in Tuvalu and beyond by couching it in these broader discourses.

While there are nine populated atolls, there are eight distinct atoll cultures, which most Tuvaluans identify themselves through; islanders from Niutao populate the small ninth island of Niulakita.

P. S. Kench, D. Thompson, M. R. Ford, H. Ogawa and R. F. McLean, “Coral Islands Defy Sea-Level Rise over the past Century: Records from a Central Pacific Atoll,” Geology 43, no. 6 (2015): 515–518.

Hiroya Yamano, Hajime Kayanne, Toru Yamaguchi, Yuji Kuwahara, Hiromune Yokoki, Hiroto Shimazaki and Masashi Chikamori, “Atoll Island Vulnerability to Flooding and Inundation Revealed by Historical Reconstruction: Fongafale Islet, Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu,” Global and Planetary Change 57, no. 3 (2007): 407–416.

The EEZ was adopted during the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (1982). UNCLOS is an international agreement on oceanic rights and regulations.

UNCLOS, in Article 121 (Regime of Islands).

Moritaka Hayashi, “Islands’ Sea Areas: Effects of a Rising Sea Level,” review of Island Studies (2013): 2.

Statement presented by Prime Minister of Tuvalu, Honourable Enele Sosene Sopoaga at the 20th Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, December 2014, Lima, Peru.

Patrick D. Nunn, “Understanding and Adapting to Sea-Level Change,” in Global Environmental Issues, ed. Frances Harris (Hoboken NJ, USA: Wiley, 2004): 45–64.

Detlef Müller-Mahn, ed., The Spatial Dimension of Risk: How Geography Shapes the Emergence of Riskscapes (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2012).

Elizabeth Yarina and Lomiata Niuatui, “Fluid Vernacular,” The Site Magazine, February 2017, http://www.thesitemagazine.com/read/fluid-vernacular.

Lomiata Niuatui, “Fakai mo Fale a Tuvalu: The Villages and Buildings of Tuvalu” (bachelor thesis, Papua New Guinea University of Technology, 1990).

Interviews in Funafuti, Tuvalu, January 2015.

Gerd Koch, The Material Culture of Tuvalu (Berlin: Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin, 1961).

Interviews in Funafuti, Tuvalu, January 2015.

Charles Hedley, “General Account of the Atoll of Funafuti. I. General Account,” Australian Museum Memoir 3, no. 2 (December 1896): 1–72.

See note 11.

John Connell, “Population, Migration, and Problems of Atoll Development in the South Pacific,” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 4, no. 1 (1995).

Teresia Teaiwa, “Native Thoughts: a Pacific Studies Take on Cultural Studies and Diaspora,” in Indigenous Diasporas and Dislocations, eds. Graham Harvey and Charles D. Thompson, Jr. (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2005): 15–36.

Epeli Hau’Ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” in A New Oceania: Rediscovering Our Sea of Islands, eds. Eric Waddell, Vijay Naidu and Epeli Hau’ofa (Suva, Fiji: The University of the South Pacific in association with Beake House, 1993): 2–16.

The NAPA projects (I and II) outline strategies that generally focus on urgent and immediate, near-term risks and issues associated with climate change: for example, food and water security, and ecosystem protections. Medium- to long-term impacts and bigger picture uncertainties, such as sea level rise, are dealt with only through incremental and small-scale adaptations such as coastal plantings or even engineered defense systems which directly work against atoll fluidity. While these programs are ostensibly propagated by the national and local government and only supported by external institutions, in reality implementation timeframes, regional and international agencies and consultants are managing, directly or indirectly, technical review processes, etc.

The United Nations Development Programme is the dominant benefactor of aid and development in Tuvalu. However, there are many, many other organizations or national entities working on the ground or providing aid to Tuvalu including: Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, the EU, the Asian Development Bank, SPREP, SPC, and also nonprofits including, TuCAN, the Red Cross, and TANGO.

“Increasing Resilience of Coastal Areas and Community Settlements to Climate Change (NAPA 1),” Project Document, Government of Tuvalu.

Traditionally, Tuvaluan land was held communally under customary tenure. Though a version of kaitasi or extended family communal ownership has been encoded in the nation’s land code, the majority of land today is privately owned with plots shrinking in size and growing in number. See Batetaba Aselu, “Tuvaluan Concept of Well-Being: Reflection on National Planning - Tek Akeega II” (PhD dissertation, Auckland University of Technology).

Elizabeth Yarina, “Post-Island Futures: Seeding Territory for Tuvalu’s Fluid Atolls,” (master thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2016).

Brendan Holden, Coastal Protection Tebunginako Village, Abaiang Kiribati (SOPAC Technical Report 136, January 1992).

Ibid.

Joeli Veitayaki, “Climate Adaptation Issues in Small Island Developing States,” in Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction: Issues and Challenges, ed. William L. Waugh, Jr. (Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Group, 2010): 380.

“Information Support for Atoll Engineering,” Tautai Foundation, July 3, 2015, http://tautai.com/information-support-for-atoll-engineering/.

See note 27; Alan Resture, “Coastal Planning Issues in Tuvalu” (unpublished manuscript, 2006).

Benjamin K. Sovacool, “Perceptions of Climate Change Risks and Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives,” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 17, no. 7 (2012): 731–52.

Orrin H. Pilkey and Katharine L. Dixon, The Corps and the Shore (Washington DC: Island Press, 1996), 40.

James C. Scott, Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven CT, USA: Yale University Press, 1998).

For a critical take on dykes along the Mississippi, see John McPhee, The Control of Nature (Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1989).

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

Simin Davoudi, “Climate Change, Securitisation of Nature, and Resilient Urbanism,” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 32, no. 2 (2014): 360–375.

Kelly Levin, Benjamin Cashore, Steven Bernstein and Graeme Auld, “Playing It Forward: Path Dependency, Progressive Incrementalism, and the ‘Super Wicked’ Problem of Global Climate Change,” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 6, no. 50 (2009).

Benjamin K. Sovacool, “Hard and Soft Paths for Climate Change Adaptation,” Climate Policy 11, no. 4 (2011): 1177–1183.

See note 9.

Frank Coffee, Forty Years on the Pacific: The Lure of the Great Ocean, a Book of Reference for the Traveler and Pleasure for the Stay-At-Home (New York: Oceanic Publishing Company, 1920).

Agricultural Report on Land Proposed for Reclamation on Maiana, Gilbert Islands, April 1967. GEIC 330/3/3. Western Pacific archives. MSS & Archives 2003/1. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

Ibid.

Ibid.

See note 25.

Ellice Islands Concrete Sea Walls, Construction of. WPHC F. 58/69. Western Pacific archives. MSS & Archives 2003/1. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

Annika Dean, Donna Green and Patrick Nunn, “Too Much Sail for a Small Craft? Donor Requirements, Scale, and Capacity Discourses in Kiribati,” in Island Geographies: Essays and Conversations, ed. Elaine Stratford (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2017): 54–77.

See note 11.

South Pacific Commission Seminar on Health Problems of Coral Atoll Populations: Water Supply Problems of Coral Atolls, February 1967, George L Chan. Western Pacific archives. Keith Chambers collection (MSS & Archives A-309) Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

Curriculum Development Progress Report, 1972, Tarawa Teachers’ College, Bikenibeau. Western Pacific archives. Keith Chambers collection (MSS & Archives A-309) Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

Mara Island, WPHC 9/II, F10/38/5 no. 129. Western Pacific archives. MSS & Archives 2003/1. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

Based on the Author’s personal involvement with the project.

“Construction Commences on Nukufetau Seawall,” Hall Contracting, 2017, http://www.hallcontracting.com.au/news/construction-commences-on-nukufetau-seawall.

“Government of Tuvalu Launches New Coastal Protection Project to Bolster Resilience to Climate Change,” United Nations Development Programme, July 2017, http://www.adaptation-undp.org/government-tuvalu-launches-new-coastal-protection-project-bolster-resilience-climate-change.

“Shoring Up Tuvalu’s Climate Resilience,” Y. Taishi, United Nations Development Programme, Asian and the Pacific, http://www.asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/blog/2017/8/29/Shoring-up-Tuvalu-s-Climate-Resilience.html.

“Funding Proposal,” Green Climate Fund, March 30, 2016, http://www.adaptation-undp.org/sites/default/files/resources/gcf_tuvalu_funding_proposal_-undp-300616-5699.pdf.

Jagime Kayanne, Takshi Hosono and Akihiroo Kawada, “The Coastal Ecosystem in Tuvalu and Geo-Ecological Management against Sea-Level Rise,” The Foram Sand Project, April 2009-March 2014.

"Tuvalu Welcomes Waterfront Recreation Area,” Hall Contracting, 2017, http://www.hallcontracting.com.au/news/tuvalu-welcomes-waterfront-recreation-area.

58.Green Climate Fund, United Nations Development Programme and the Government of Tuvalu, “TCAP LPAC Minutes,” February 2017.

See note 56.

"Saving the Sinking Islands of Tuvalu with Star Sand,” Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS), 2008, https://www.jst.go.jp/global/english/case/environment_energy_3.html.

See note 38.

See note 60.

See note 56.

The program is structured as a collaboration between the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), which provides competitive research funds for science and technology projects, and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), which provides competitive research funds for medical research and development, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which provides development assistance (ODA).

http://www.jst.go.jp/global/english/case/environment_energy_3.html,

http://www.jst.go.jp/global/english/kadai/h2002_tsuvalu.html.

See note 46.

Dirk De Meyer, “Growing an Island: Okinotori,” San Rocco 1, no. 1 (2011): 23–29.

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 10 December 1982, Part VIII, art. 121(1).

See note 66.

“Japan is Growing an Island,” CORRECTIV, https://correctiv.org/en/investigations/climate/article/2017/07/28/sea-rise-japan-Okinotorishima/.

“Our Projects: Nanumea Atoll,” Seacology, last updated January 2011, https://www.seacology.org/project/78-tuvalu/.

“ANNEX 4: Island Profiles and Justification for Selection within the Tuvalu R2R Project,” UNDP.

Eric L. Gilman, Joanna Ellison, Vainuupo Jungblut, Hanneke Van Lavieren, Lisette Wilson, Francis Areki, Genevieve Brighouse et al., “Adapting to Pacific Island Mangrove Responses to Sea Level Rise and Climate Change,” Climate Research 32, no. 3 (2006): 161–176.

Jurgenne H. Primavera and J. M. A. Esteban, “A Review of Mangrove Rehabilitation in the Philippines: Successes, Failures and Future Prospects,” Wetlands Ecology and Management 16, no. 5 (2008): 345–358.

See note 46.

Donna C. Mehos and Suzanne M. Moon, “The Uses of Portability: Circulating Experts in the Technopolitics of Cold War and Decolonization,” in Entangled Geographies: Empire and Technopolitics in the Global Cold War, ed. Gabrielle Hecht (Cambridge MA, USA: The MIT Press, 2011), 43–74.

Pablo Alejandro Leal, “Participation: the Ascendancy of a Buzzword in the Neo-Liberal Era,” Development in Practice 17, no. 4-5 (2007): 539–548.

Warwick E. Murray and John D. Overton, “Neoliberalism Is Dead, Long Live Neoliberalism? Neostructuralism and the International Aid Regime of the 2000s,” Progress in Development Studies 11, no. 4 (2011): 307–319.

The authors also have extensive personal familiarity of the Tuvaluan atolls and peoples due to both academic and professional links.

Arthur P. Webb and Paul S. Kench, “The Dynamic Response of Reef Islands to Sea-Level Rise: Evidence from Multi-Decadal Analysis of Island Change in the Central Pacific,” Global and Planetary Change 72, no. 3 (2010): 234–246.

Wendy Zukerman, “Shape-Shifting Islands Defy Sea Level Rise,” New Scientist, June 20, 2010, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20627633-700-shape-shifting-islands-defy-sea-level-rise/.

Gerald Traufetter, “Not so Much Trouble in Paradise: Are Coral Islands Really Doomed?” Spiegel Online, July 23, 2010, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/not-so-much-trouble-in-paradise-are-coral-islands-really-doomed-a-707884.html.

See note 79.

Sophie Webber and Simon D. Donner, “Climate Service Warnings: Cautions about Commercializing Climate Science for Adaptation in the Developing World,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 8, no. 1 (2017).

Adam Grydehøj and Ilan Kelman, “The Eco-Island Trap: Climate Change Mitigation and Conspicuous Sustainability,” Area 49, no. 1 (2016).

See note 24.

Michael Goldsmith, “The Big Smallness of Tuvalu,” Global Environment 8, no. 1 (2015): 134–151.

Richard Benwell, “The Canaries in the Coalmine: Small States as Climate Change Champions,” The Round Table 100, no. 413 (2011): 199–211.

Carol Farbotko, “Wishful Sinking: Disappearing Islands, Climate Refugees and Cosmopolitan Experimentation,” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 51, no. 1 (2010): 47–60.

Joeli Veitayaki, P. Manoa and A. Resture. “Pacific Islands and the Problems of Sea Level Rise Due to Climate Change,” in Proceedings of the International Symposium of Islands and Oceans (Tokyo: Ocean Policy Research Foundation, 2009): 55–69.

Sonia Leonard, Meg Parsons, Knut Olawsky and Frances Kofod, “The Role of Culture and Traditional Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia,” Global Environmental Change 23, no. 3 (2013): 623–632.

Patrick D. Nunn, “Responding to the Challenges of Climate Change in the Pacific Islands: Management and Technological Imperatives,” Climate Research 40, no. 2-3 (2009): 211–231.

See note 28.

Anders Blok, “Assembling Urban Riskscapes: Climate Adaptation, Scales of Change and the Politics of Expertise in Surat, India,” City 20, no. 4 (2016): 602–618.

Erik Swyngedouw, “Depoliticized Environments: The End of Nature, Climate Change and the Post-Political Condition,” Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement 69 (2011): 253–274.

Available at: http://tautai.com/video-funafuti-masterplan/

See note 28.

“Atoll Engineering for Coastal Resilience,” Tautai Foundation, May 27, 2015, http://tautai.com/atoll-engineering-for-building-resilience/.

Matt Siegel, “A Tiny Pacific Island Nation That Does Not Smell like Paradise,” The New York Times, October 16, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/17/world/tuvalu-a-pacific-landscape-befouled.html.

G. Baldacchino, “Seizing History: Development and Non-Climate Change in Small Island Developing States,” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management (2017).

Lawrence Caramel, “Besieged by the Rising Tides of Climate Change, Kiribati Buys Land in Fiji,” The Guardian, July 1, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jul/01/kiribati-climate-change-fiji-vanua-levu.

Simon D. Donner and Sophie Webber, “Obstacles to Climate Change Adaptation Decisions: a Case Study of Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Protection Measures in Kiribati,” Sustainability Science 9, no. 3 (2014): 331–345.

Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/ki/ki-nbsap-v2-en.pdf.

“The Village that Banned Seawalls,” Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), July 8, 2015, http://www.sprep.org/climate-change/the-village-that-banned-seawalls.