Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

This paper examines rubble management as an important but often neglected component of disaster response and a powerful example of the frequent disconnect between national plans and local action. It focuses on five marginalized municipalities in Oaxaca, Mexico: Ciudad Ixtepec, Asuncion Ixtaltepec, El Espinal, Juchitan de Zaragoza, and Santa Maria Xadani. These constitute the region most affected by the Mexican earthquakes of September 2017, with roughly 58% of inhabitants suffering either partial or total loss of their houses. The paper builds on the results of fifty-one interviews, a cross-sectional survey with 384 residents, and a mapping analysis to reveal the challenges of post-disaster planning across scales. The results show that local perspectives were given little consideration in nationally-led rubble management plans, and that these documents were likely shaped by concerns over what constituted institutional legitimacy, rather than attention to local context. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings through the lens of institutional isomorphism and offers recommendations for more effective post-disaster rubble management, particularly centered on increasing the involvement and capacity of residents, municipal governments, and other key institutions.

Disasters are increasing in frequency and scale, and growing numbers of people are vulnerable to their impacts.1 For example, more than 90% of cities in countries designated by the United Nations as “low-income” have high vulnerability to disaster-related mortality.2 In light of this, scholars have argued that further research is needed on the medium and long-term aftermath of disasters.3 This is particularly true of studies that examine the decision-making processes underlying the creation and implementation of response and recovery plans, especially regarding relatively understudied aspects of disasters such as rubble clearance.4

This paper contributes to the literature on planning approaches in low-income, post-disaster contexts. Plans in such settings tend to overlook the importance of local action and are too often dismissed during emergencies.5 The paper focuses on events that unfolded in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca after a series of earthquakes in September 2017.

It compares the reality of local, post-disaster response, particularly concerning rubble, with the expectations of national plans. The study seeks to better understand how local efforts are supported or undermined by national plans, with a goal of providing insights that might lead to better planning across scales in contexts like Oaxaca.

The paper begins with a brief overview of the impact of disasters, particularly regarding rubble management, in marginalized and risk-prone areas of the Global South. It then examines the events that unfolded in the study region. In particular, the study focuses on five municipalities located along the Los Perros River, in Mexico’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec region.6 These municipalities are Ciudad Ixtepec, Asuncion Ixtaltepec, El Espinal, Juchitan de Zaragoza, and Santa Maria Xadani. The results draw on fifty-one interviews with critical actors spanning sectors and scales, a cross-sectional survey with 384 residents, and a mapping analysis. The paper concludes with a discussion of the findings through the lens of institutional isomorphism and provides suggestions for more effective post-disaster rubble management, particularly centered on increasing the involvement and capacity of residents, municipal governments, and other key institutions.

POST-DISASTER RUBBLE MANAGEMENT IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH

A significant area of concern in much of the Global South is the development of feasible plans to manage the aftermath of crises in marginalized communities, especially those related to topics that are often regarded as “secondary,” such as rubble management. This is especially relevant because, even though experts sometimes argue that communities should consider relocating based on continued social and environmental vulnerability, history shows that the vast majority of settlements are rebuilt in place after disasters.7 Likewise, there is evidence that, following disasters, a lack of communication and collaboration between governmental institutions and local actors can further enhance vulnerability.8

Despite being recognized as a significant global challenge, few plans exist that address post-disaster waste or rubble management.9 As Brown et al. explain, this happens because “financial, technical and expert resources in developing countries are generally a limiting, if not prohibitive, factor in achieving disaster risk reduction goals.” 10 Moreover, where plans or guidelines do exist, they are generally limited to describing “what” can be done with rubble rather than “how” to achieve such solutions, especially in contexts where resources were already meager in the first place.11 This often results in rubble mishandling, which can quickly turn a potentially “manageable” disaster into a full-blown crisis. For example, experts argue that dealing with construction waste is a complicated process that often results in the creation of suboptimal fixes, such as unsecured and polluting landfills.12 This happens, in part, because officials tend to favor “simple” and quick fixes in the absence of a clear plan (or presence of a weak one). Such unprotected landfills raise significant environmental concerns, as disaster-related rubble usually contains a wide range of solid and liquid waste, including electronics, organic matter, vehicles and machinery, oils, solvents, industrial material, and other hazardous waste components.13

This paper makes a number of contributions. First, it seeks to better understand how planning across scales can be improved in post-disaster settings in the Global South. This is important given the frequently problematic and chaotic nature of local responses to disasters. Second, the paper makes a contribution by responding to demands by scholars for better knowledge of cases where “environmental standards have been reduced – addressing why the decision was made, what information the decision was based on, and what the impact of the option was.” 14 As this article will elaborate, post-earthquake Mexico, and especially Oaxaca, is a highly instructive case for understanding the complexity of post-disaster planning, particularly around rubble management.

In Mexico, as in much of the Global South, clear, feasible, and contextualized disaster response plans seldom exist.15 Moreover, the few that do are often created after disasters strike. For example, Mexico developed its first disaster policy the year after the 1985 Mexico City earthquake. That plan has been described as insufficiently comprehensive. Diaz states that the plan reflects “the adoption in Mexico of a “civil protection” focus, to the detriment of a logic of “comprehensive risk management” that would have privileged the reduction of vulnerabilities and not only the attention of emergencies.” 16

The site for this study is post-earthquake Oaxaca, the second most impoverished state in Mexico, where 70.4% of the population lives in poverty.17 Oaxaca is one of three Mexican states to have a Human Development Index (HDI) below the world average, and its score of 0.681 is comparable to that of Botswana.18 It is located in the southeast of Mexico, close to the border with Guatemala and has 570 municipalities, the majority of which are small or rural. These account for over a fifth of Mexico’s total of 2,457 municipalities.19 Most of the state’s communities are separated by mountain ranges and connected by precarious roads, which has allowed maintenance of significant cultural diversity. For example, the state has fourteen indigenous languages (with significant variations within each), spoken by over a third of its residents.20 Oaxaca’s easternmost region is part of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a 220 km (136.7 mi.) wide territory that connects the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and which also includes parts of the states of Chiapas, Veracruz, and Tabasco.

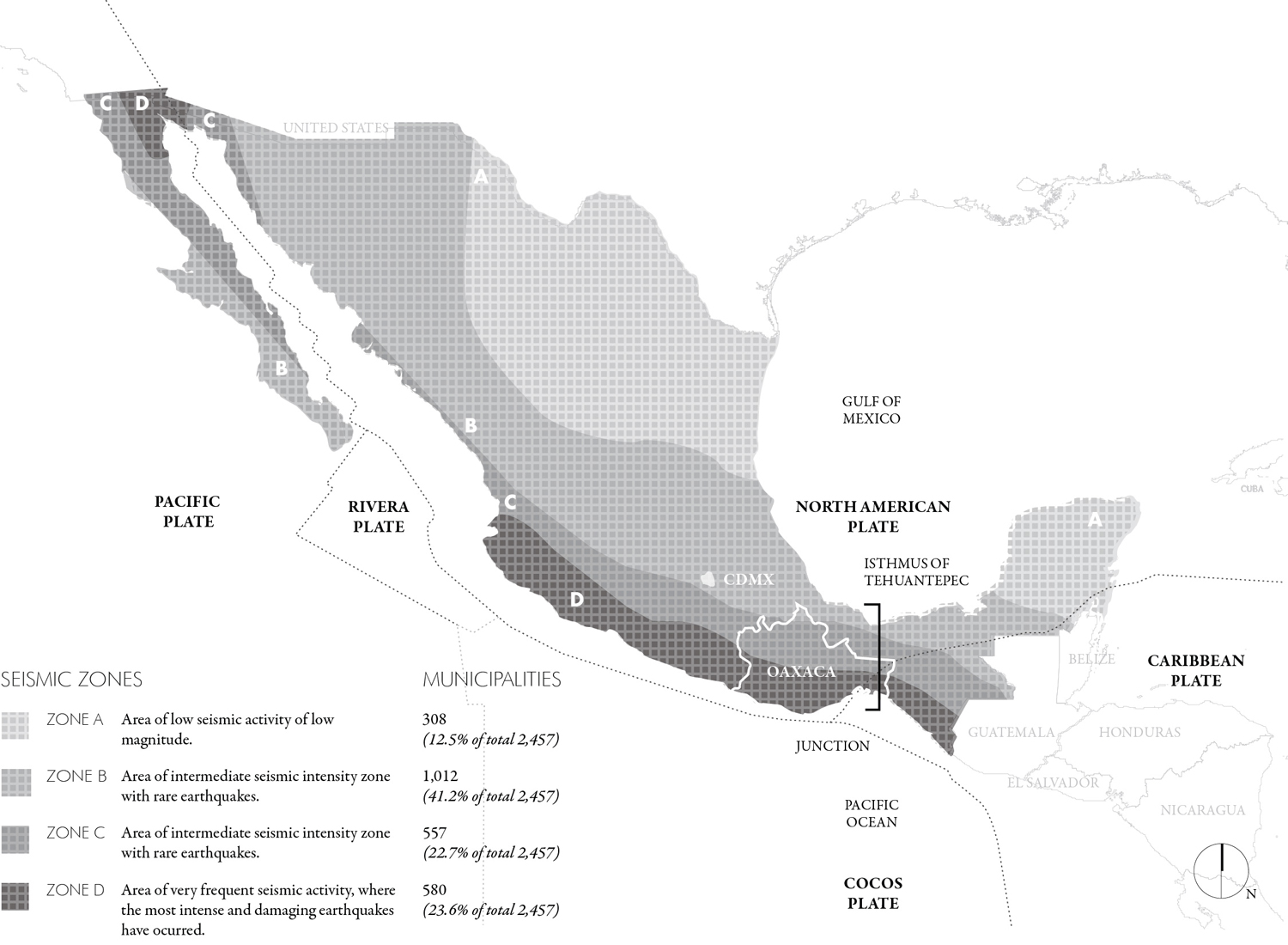

This paper centers on the southern coast of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a historically isolated region prone to earthquakes, floods, and strong winds. This region lies close to the junction of the North American, Cocos, and Caribbean tectonic plates, and is partially located in Mexico’s seismic zone D (Fig. 1).21

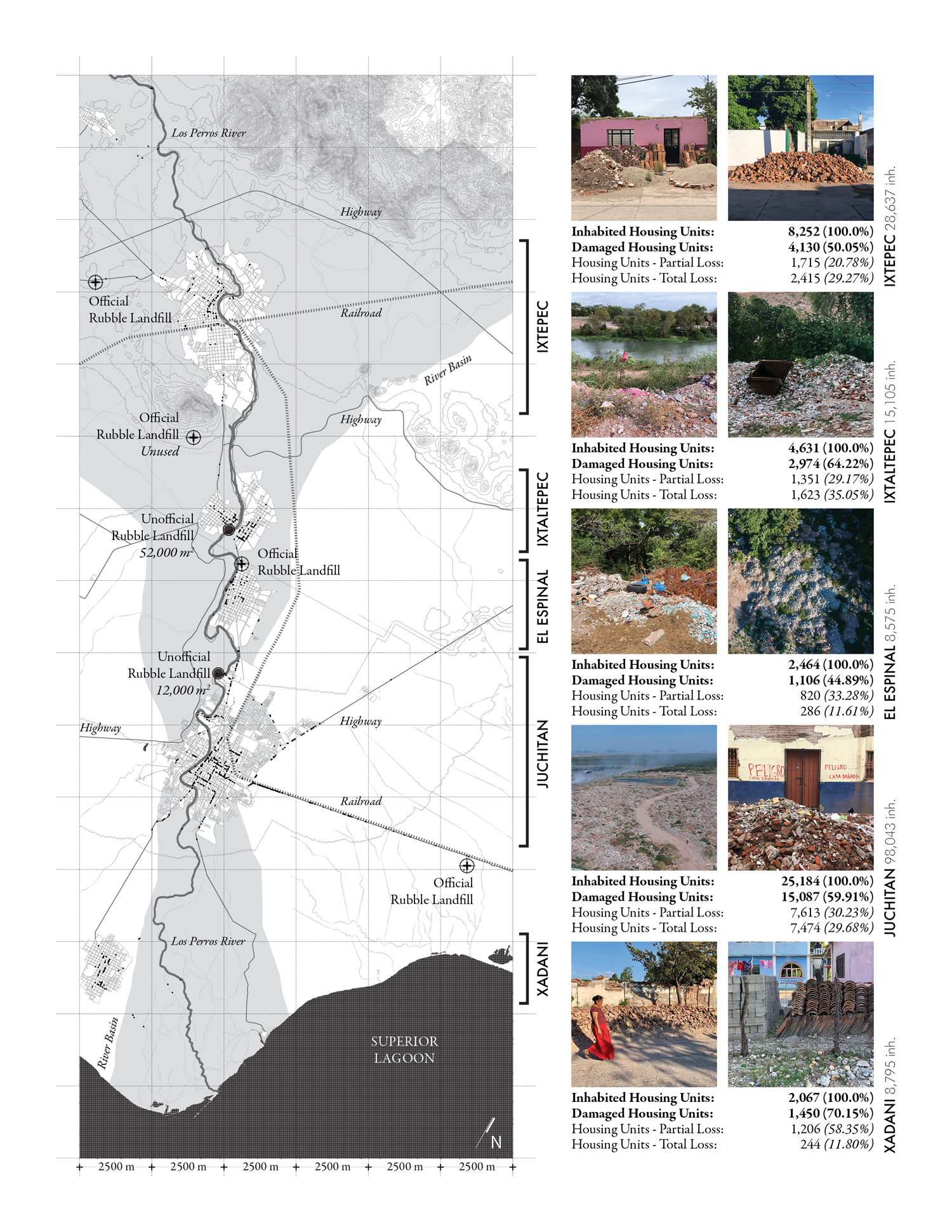

Zone D has soils that can exceed 70% of the acceleration due to gravity (which may lead to soil liquefaction), and it has the highest number of earthquake epicenters registered by the Mexican National Seismological Service (SSN).22 In short, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is vulnerable to seismic activity that can easily result in significant economic and livelihood losses. In addition, the narrowest part of the isthmus does not exceed 300 m (934 ft.) in elevation, making it flood-prone and susceptible to wind gusts that can reach up to 200 km (124 mi.) per hour.23 Within the isthmus, the specific focus area of this study is the riverine corridor of the Los Perros River, the area with the highest damage resulting from the earthquakes of September 2017 (Fig. 2).24

On September 7, 2017, an 8.2 Mw earthquake struck the south of Mexico. It was the strongest earthquake recorded to date in the country, and has been called “the strongest of the century.” 25 Twelve days later, on September 19, the North American plate ruptured in the center of the country, causing a 7.1 Mw earthquake that primarily affected Mexico City and its surrounding states: Morelos, Puebla, and the State of Mexico. This second event happened, to the day, precisely thirty-two years after the most destructive quake to strike the capital, the 8.1 Mw earthquake of 1985.26

As a result, global and national attention shifted to Mexico City, downplaying international response and engagement in areas like the Oaxaca. A third earthquake, with a magnitude of 6.1 Mw, hit the south of the country again on September 23, 2017. Together, these events caused a simultaneous state of emergency in six of Mexico’s thirty-two states, an unprecedented situation.27

Responses varied significantly across Mexico. As civilians, state officials, soldiers, nonprofits, private companies, and international aid groups mobilized swiftly to work in Mexico City, the federal response in Oaxaca was fragmented due to the widespread emergency. Notably, local authorities and civilians in Oaxaca did not have the same experience and resources as those in the capital. After the 1985 earthquake, Mexico City invested significant amounts of human and economic resources in capacity building regarding disaster response and prevention and developed stricter construction regulations. In contrast, places like the Isthmus of Tehuantepec were seemingly unaware of the imminent danger they faced regarding earthquakes, and they had no documented plans and procedures to build on. The last significant earthquakes near the study area happened in 1787 and 1931.28 The official intensity of the 1787 earthquake is unknown, as the SSN was only launched in 1910, but it is estimated to have neared 8.6 Mw. According to the Gazette of Mexico, it caused “the great Mexican tsunami” west of the isthmus.29 The latter, in 1931, ravaged Oaxaca de Juarez, the state capital. Although widely felt on the isthmus, these historic earthquakes did not alter the region’s preemptive practices significantly, and communities were unprepared for the scale of disaster that unfolded in September 2017.

The 2017 earthquakes struck the southern area of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec the hardest, leaving the corridor along the Los Perros River with the most damage in the whole country. This area includes the five small and mid-sized municipalities under study. An estimated 58% of these cities’ 159,155 inhabitants suffered partial or total loss of their houses. The damage ranged from a high of 70.2% of households affected in Santa María Xadani to a low of 44.9% of households in El Espinal.30 Moreover, the disaster left around 1.275 tons (2.8 million lb.) of rubble (equivalent to the weight of 12,200 blue whales) spread along highways, streets, “temporary” landfills, and, unfortunately, the already heavily polluted banks of the river.31 Rubble constituted a major challenge for the cities of Oaxaca and many attempted a variety of responses to manage this crisis, including efforts that directly contradicted national plans and were even illegal. Notably, one municipality, Asuncion Ixtaltepec, created an unsecured and polluting landfill to contain rubble and, officials argued, to serve as a flood barrier. The process through which this intervention, and others like it, arose was tumultuous, and it will be one of the focal points of the next sections.

METHODOLOGY

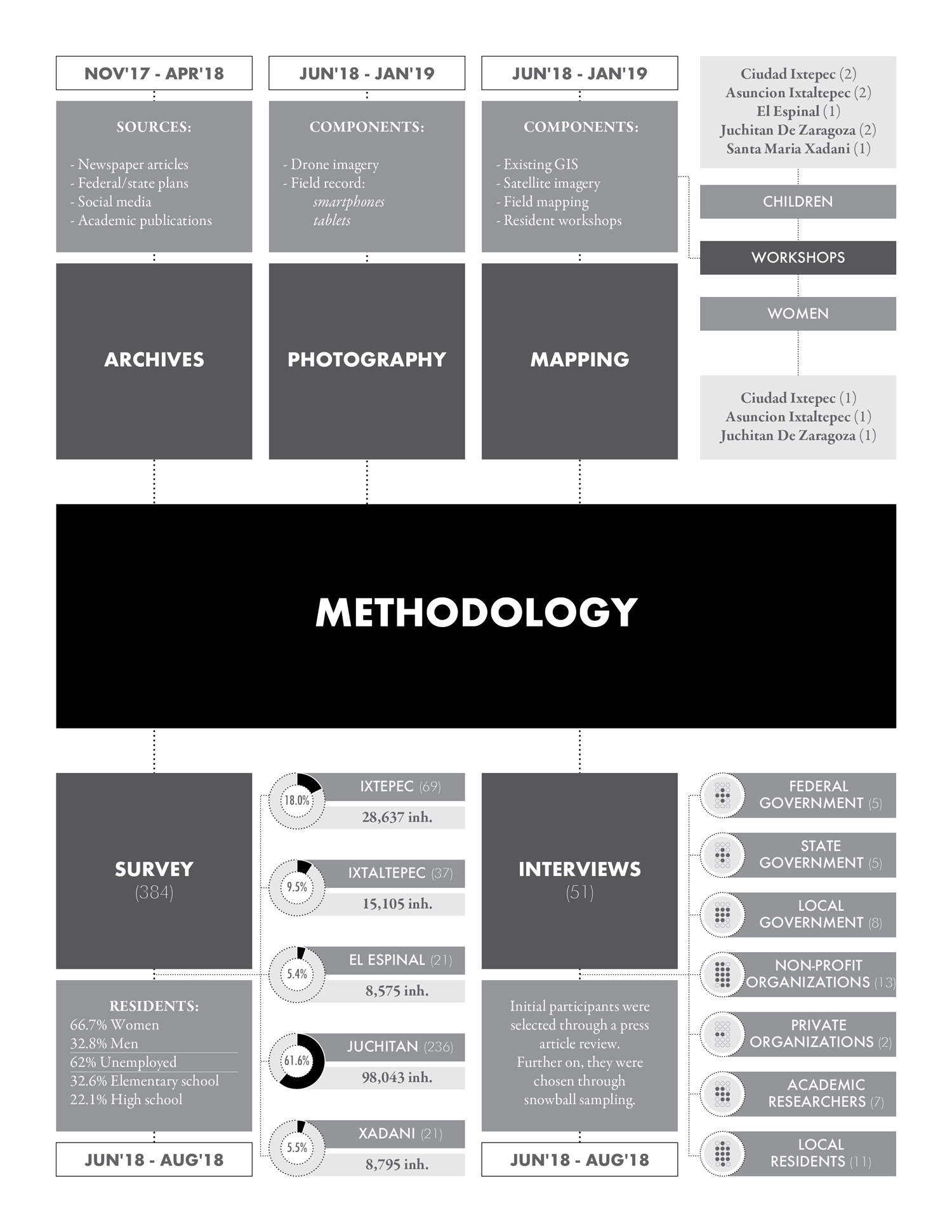

The research reported here was conducted between November 2017 and January 2019 using a mixed methods approach and drawing on quantitative and qualitative data. Initial archival research, examining the history and current state of disaster response in Oaxaca, happened between November 2017 and April 2018, followed by a three-month period of fieldwork in Mexico between May and August 2018. The specific project reported here was part of a broader investigation of post-disaster response in Oaxaca.32

To uncover the relationship between national level plans and local post-disaster action, the research sought to first understand the nature of existing plans for disaster response, including for rubble management. To this end, it collected all existing post-disaster rubble plans in Mexico. Notable among these were the nationally-produced “Guidelines for the Management of Construction and Demolition Waste Generated by Earthquake in the States of Oaxaca and Chiapas,” created by Mexico’s Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) in 2017. To understand perspectives on the ground, fifty-one interviews were conducted with residents and key actors working at a variety of scales, as well as a randomized-sample survey on disaster recovery with 384 residents of the five municipalities (Fig. 3).

The randomized survey focused on seventy-two questions concerning rubble management, perceptions of post-disaster action, and personal experiences with rubble. The study also undertook photographic documentation and a detailed mapping study of rubble in the five study municipalities. The mapping analysis drew on eleven mapping workshops with local women and children and data collected by researchers on the ground.

Interviewees were selected through snowball sampling and included five federal officials, five state officials, eight municipal officials, thirteen non-profit representatives, two private-sector workers, seven academics, and eleven residents. The interviews concentrated predominantly on officials’ and professionals’ perspectives because the survey, in contrast, was focused on resident households. Nonetheless, some residents were included to allow deeper inquiry the attitudes examined in the survey. For the interviews, the researchers first identified, from media reports and public documents, a list of key players in local post-disaster rubble management for initial meetings. The pool of interviewees was expanded based on referrals from the initial participants. All interviews were conducted in Spanish. Each person was interviewed once, and the conversations lasted between one to two and a half hours. The interviews were structured around three open-ended questions regarding the immediate response to the 2017 earthquakes, the state of recovery and rubble management until the point of the interview, and the role or potential role of each interviewee in post-earthquake action in Oaxaca. From these initial questions, the conversation moved freely to other related topics raised by interviewees or interviewers.The interview transcripts were coded manually to identify overarching categories in the responses, as well as commonalities and differences between interviewees. Upon conclusion of the interviews, some of the participants (particularly residents and non-profit representatives) offered to act as links between the researchers and other community members, becoming central to the photographic and mapping investigations of the site.

Maps of rubble in the study area were developed from diverse sources. These include spatial datasets produced by the researchers regarding the location of rubble (made with GPS trackers), the findings from eleven participatory mapping workshops conducted across the five municipalities, and existing Geographic Information System (GIS) layers produced by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). The researchers worked with several government agencies to attain all available data regarding the geographic characteristics of earthquake damage, the built environment, official rubble disposal sites, local topography, and the riverine basin. Even though the government’s pre-existing GIS data, on which such maps are based, was public, it was often challenging to obtain. For this reason, it was supplemented by the researchers’ own spatial data collection efforts. Such collection focused on the location of unofficial rubble disposal sites, landfills, water treatment and waste management infrastructure, critical flood risk points along the river, and areas of water runoff. Visual documentation drew on imagery from drone flights and photography of key rubble sites using tablets and smartphones.

The participatory mapping workshops served to qualitatively explore how inhabitants of the region understand their urban and natural environment, particularly in the context of post-disaster life. Each of the eleven workshops was carried out with groups of 8-10 adult women and children in each municipality to create visual representations, maps, and diagrams that focused on three primary issues: changes in the built environment after the earthquakes, seasonal floods, and perceptions of and interactions with the Los Perros River. Participants in the mapping workshops were identified through an open call for participation, made through local radio and tv stations, as well as through public addresses made from loudspeakers mounted on vehicles that travel through each municipality (known as perifoneos).

Lastly, the cross-sectional survey was administered to a random sample of residents. The allocation of respondents by municipality was determined in proportion to their population size. Of the 384 respondents, 69 were in Ciudad Ixtepec (18.0%), 37 in Asuncion Ixtaltepec (9.5%), 21 in El Espinal (5.4%), 236 in Juchitan de Zaragoza (61.6%), and 21 in Santa Maria Xadani (5.5%). Participants were 18 years or older and had to have lived in the same residence for at least ten years to ensure they could speak knowledgeably regarding the nature of vulnerability and the history of disaster planning in the locality. Since cadasters did not exist for the municipalities, the study randomly selected blocks to obtain one interviewee per block. The selected houses in each block were chosen systematically, beginning in the northwest corner and moving clockwise until surveyors obtained a response. If no one was willing to respond, the block had no eligible residents, or if the block had no houses, surveyors moved on to the next randomly selected block. The survey contained seventy-two questions regarding personal identification, the Los Perros River, floods, earthquakes, rubble management, waste management, post-disaster aid perceptions, culture and identity, public space, and economy, safety, and health. The research team hired two groups of eight surveyors each, all of whom were local young adults. Survey administration lasted five weeks.

RESULTS

The results can be summarized in five main points. These are described in further detail below.

1.Despite the recurrent nature of disasters, response plans were created retroactively, prioritizing reaction and short-term action instead of prevention and long-term planning.

As described in the introduction, there are limited disaster management plans in place in Mexico, as is the case in many other areas of the Global South.33 When asked about the nature of disaster planning, 67% of interviewees complained of not having preemptive response plans despite facing recurrent disasters. This is best reflected in two interviewee quotes. The first was from a federal official, who worked for over two months in Oaxaca immediately after the earthquakes. He stated:

There was no long term plan. The president’s role was to go around the stricken communities and order people to work intensely...Showing up is not the same as having a plan. The only thing that resembles a disaster response plan is the [national civil aid and relief plan], but even that one is not concrete. In short, it says that we need to do whatever is necessary to solve any problems we find.34

The second is from the president of the Los Perros River Basin Committee, who is frequently forced to address the impacts of disasters. With regard to the frequent problem of flooding, a common form of disaster in the region, he stated:

There is no preemptive plan. [The state] waits for the flood to come and then they see what they can do. I have said several times that we do not want aid; we want preemptive programs. It would even be cheaper. But it might not even be about the cost. It is all clientelism. Politicians “need” these problems to be in good standing when they “solve” them.35

Regarding rubble, the lack of preemptive plans was again evident. A review of existing plans showed that all plans that could be identified for rubble management in Mexico were created in the weeks after the 2017 earthquakes. This was extremely problematic since rubble clearance should ideally begin within the first week and a half following a disaster, in order to enable the efficient delivery of aid and to ensure that other aspects of response and recovery can begin.36 In the study municipalities, the first official meeting to discuss rubble management occurred almost two weeks after the first earthquake, on September 20, 2017. This meeting resulted only in federal authorities agreeing to find “suitable” disposal sites in each municipality, away from protected areas, wetlands, and water channels.37 Therefore, federal officials helped local authorities define the ideal location for the permanent rubble landfills in each municipality. Notably, official plans for managing rubble, in the form of construction waste, in Oaxaca and Chiapas were only published by SEMARNAT, the national department of environment and natural resources, on November 6, 2017, almost two months after the first earthquake and a month and a half after the first meetings in the locality.38 In the meantime, local leaders were forced to take action on their own. For example, the mayor of Asuncion Ixtaltepec began construction of a large, illegal, and unprotected riverside landfill for rubble in the center of the town, which local officials argued was meant to serve as a barrier against river overflows (Fig. 4). The site of this landfill spans almost 1,5 km (0.932 mi.), is far from the nationally-established landfill location (left unused), and cuts across the center of the town. The rest of the five municipalities relied on help from private companies to discard rubble, generally with very limited oversight, resulting in widespread disposal along highways and streets, in unofficial landfills, and at other riverside locations (Fig. 5).

Left: Map showing the location of official and unofficial rubble disposal sites in each of the five municipalities as of August 2018. Each black dot represents a site where the researchers found piles of rubble. Right: Images of rubble in each municipality, together with data on damage levels, compiled as of January 2019.

2.National disaster response plans were conceived with large cities in mind, despite the prevalence of smaller disaster-prone municipalities and rural areas.

Sixty-nine percent of interviewees argued that Mexico’s national disaster plans were conceived with large cities in mind. Indeed, even local plans, to the extent they existed, were considered by many interviewees and survey respondents to focus on tasks that only Mexico City could accomplish. One particularly good example of the way in which plans failed to consider local contexts, in favor of a capital-centric view, was heard in an interview with the mayor of Asuncion Ixtaltepec (Fig. 6).

In that interview, he explained his desire to replicate one of the most upscale streets in the capital in his devastated and impoverished municipality. He stated:

I have made this reconstruction my personal project. For example, I would like to re-establish the main avenue. It will surpass [Presidente] Masaryk Avenue [in Mexico City] because it will grasp urbanity better and incorporate colonial ideals. For the river, I envision a pier with vast public spaces. We will have basketball, beach volleyball, and indoor soccer fields.39

Mirroring the mayor’s focus on Mexico City, there was only limited attention to the realities of Oaxaca in plans for post-disaster response. Almost a quarter (23.6%) of Mexico’s municipalities, most of which are small and under-resourced, are located within seismic zone D, the most active in Mexico (see Fig. 1). However, there are only limited disaster response plans specific to this zone. Furthermore, the existing plans are based on those created for Mexico City. For example, all construction-related regulations for Mexico’s states are modeled after those created for the capital after the 1985 earthquake. A similar process of emulation occured around rubble management in 2017, with all plans following the template produced for Mexico City.

The initial plan for addressing post-disaster rubble in Mexico was developed by SEMARNAT for Morelos, Puebla, Mexico City, and the State of Mexico, and it was published on September 29, 2017, ten days after the earthquake that hit the country’s center (the second of the overall series) on September 19. As previously stated, the nationally-produced plan for the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas was published on November 6, 2017. Surprisingly, both plans, for the two sets of states, are virtually identical, with variation only in the cover page images and index of affected municipalities. Yet, each of the two groups of states in question have distinct environmental, socioeconomic, and political conditions. Building on these two initial nationally-led rubble plans, the state government of Oaxaca created a third virtually identical rubble management plan. Although its official publication date is unclear, this document was created at some point after February 2018, and it is virtually identical in content to the prior two rubble plans. In summary, the plans made for addressing rubble in local contexts failed to take specific conditions into account and, in fact, merely replicated those developed for the nation’s capital.

Reinforcing the lack of relevance of nationally-produced disaster plans for places like Oaxaca, there are several points within the nationally-produced rubble management plan for Oaxaca and Chiapas that clearly cannot be, nor are meant to be, implemented in small and mid-sized cities such as those under study. For example, the guidelines state that “the final disposal site must have a hydraulic infrastructure that allows proper drainage of the rainwater runoff both inside the site and on its perimeter, to ensure proper circulation of water.” 40 However, places like Juchitan de Zaragoza, the biggest municipality of those studied here, suffer from very frequent floods caused by sewage infrastructure deficiencies. The five municipalities under study do not currently have, and likely will not have in the near future, the capacity to construct such a complex drainage system for a rubble landfill. The infeasibility of achieving the kinds of drainage and hydraulic infrastructure mentioned in the nationally-produced rubble plan were also confirmed by the mapping analysis, which showed that all five municipalities suffer from sewer and drain overflows, in addition to floods caused by the river (Fig. 7).

3.Fragmented post-disaster action emphasized municipal boundaries, rather than a regional understanding of the affected territories.

The interview and survey results show that centralized responses to the disaster in Oaxaca gave little consideration to local conditions, including pre-existing cultural, environmental, and economic networks. Moreover, they operated in a fragmented way across municipalities, with little regional coordination. According to all federal officials interviewed, each national government department received orders from the Mexican president to oversee disaster response in a specific municipality, leading to highly divergent and uncoordinated approaches being adopted at different sites within the affected regions. Such divergent approaches were implemented in the Los Perros River corridor, which, like other regions, would have benefited from integrated action. In areas like Oaxaca, with a strong cultural identity and a history of social mobilization, the top-down approach of the Mexican government caused marked tensions between government officials and local residents, complicating the response process. For example, one of the federal officials that worked in the area for several months after the earthquakes stated:

Locals did help us, but it was very complicated. They had a very unfavorable attitude sometimes. They expected [the authorities] to do all the work. A great tension arose, particularly with the army, because, upon arriving to help and asking for local support, the soldiers would receive responses like: “I will not help you. I am not paid for doing this work, but you are. So do it.” I understand that they were probably scared or did not quite know what to do to help, but many were not willing to cooperate with us either.41

On the other hand, local residents emphasized in their interview and survey responses that they believed that many of the policies and procedures implemented during the recovery process, especially regarding housing, were completely inadequate for their context and lifestyles. This is well expressed in the following quote by a state official from Ciudad Ixtepec:

Oaxaca is like eight different Oaxacas. People from the valleys are not the same as people from the coast, the isthmus, or the hills. We are very different, but few outsiders understand those nuances. What we do have in common is that we are very complicated. However, plans have not considered the idiosyncrasy of the people. There is a lot of resistance. There was no design for the reconstruction process that kept the cultural or historical values. So now, what we have is that everyone is rebuilding as they want and as they can. The area will lose its sense of identity.42

Overall, 49% of interviewees shared the sentiment that post-disaster policies, including those related to rubble management, did not consider local conditions. With regard to rubble management, the lack of local contextualization and detail resulted in nationally-produced plans that disregarded the riverine corridor as an ecology of any kind. There is no mention in the plans of regional cooperation (or even “region” as a term), despite the towns’ interrelated and interconnected societies and economies. As a local resident stated:

[To my knowledge] there was no rubble management plan or territorial development vision. Responders came and saw a great business opportunity in housing production and rubble clearance, which was not concerned at all about construction waste. If people’s well-being was not their priority, waste certainly was not either.43

4.Plans ignored economic incentives, allowing for new marketdynamics in which profits, resources, and knowledge went to the “highest bidder.”

The results reveal that many interviewees felt strongly that nationally-produced post-disaster plans, including those for rubble, failed to adequately take into account economic factors and, in so doing, created new, and negative market dynamics. This sentiment was felt most strongly by interviewed local residents (82%) and representatives of non-profit organizations (70%), although it was also widely shared across all interviewee groups, being reported by a total of 69% of the interviewees. As an example of this phenomenon, the National Fund for Natural Disasters (FONDEN), administered by the Secretariat of Agrarian, Land, and Urban Development (SEDATU), distributed debit cards to each person who, according to much contested official records, either lost their house completely or suffered partial damage.44 The greatest amount a person could receive was 120,000 pesos (6,289 USD) 45 of which 75% was for purchasing construction materials from a pre-authorized store and 25% was for labor. Interviewees highlighted three problems with this solution. First, many vernacular construction materials, such as wood and clay tiles, could not be bought at authorized stores. Second, given the shortage of resources and trained construction workers, labor and material costs skyrocketed after the disaster, making the funds insufficient. Finally, this pushed locals to transfer their aid packages to private developers that came to each town offering to demolish their traditional homes in exchange for a 40 m2 (431 sq. ft.) concrete house that completely disregarded local building traditions, lifestyles, and climatic conditions (Fig. 8).

The result was unnecessary demolitions which further complicated rubble management.

The economic dynamics created by the earthquakes, and which were exacerbated by nationally-produced planning efforts, were expressed very clearly by the interviewees. All local resident interviewees expressed similar concerns: that traditional houses were rapidly disappearing due to ill-conceived, poorly planned, and top-down reconstruction policies. Describing the new economic forces that developed following the disaster, residents reported that local masons charged more than twice their regular rate during the reconstruction process, which pressured them to give in to the offers of private developers. One resident of Juchitan de Zaragoza described the situation as follows:

Brigades of all kinds came to help. SEDATU managed them and was in charge of releasing the goal: demolish. That was their official slogan, even though CENAPRED [the National Center for Prevention of Disasters] recommends to shore up and assess the extent of the damage before making any decisions. Think about it; it was an excellent business. If in Juchitan there were 8,000 houses in a state of total loss and each one received 90,000 pesos (4,700 USD) in materials cards, there was a large money fund captive for private companies. Multiply it: we are talking about 720 million pesos (38,085,805 USD).46 Many entrepreneurs came to spin around. They rubbed their hands and toured the area with SEDATU. They pressured demolition with false threats, saying that those who did not demolish would not get the 120,000 pesos (6,289 USD).47 Then, people began to demolish without thinking first if it was right or wrong. [Federal officials] told me “demolish, demolish, demolish” and I said “mangos, mangos, mangos [no way].” This house belonged to my great grandmother.48

Notably, the national government’s rubble management plan for Oaxaca and Chiapas contains no discussion of economic or market conditions, either concerning how these might unfold or how they might be managed. The only official effort to address economic concerns around recovery, including regarding rubble management, was spearheaded by the national Secretariat of Communications and Transportation (SCT) through the creation of a temporary employment program. This program offered a total payment of 1,185 pesos (62 USD) 49 for local residents to help clear the rubble from their own plots. Nonetheless, local interviewees reported that this financial aid was merely symbolic, as they were not officially required to carry out the work (causing many people not to do so).50 The consequence was that the compensation offered was insufficient to motivate actual clearance of rubble, and, while giving the impression that a policy was in place to incentivize action on rubble, likely led to very little change in actual rubble conditions.

5.Rubble management plans had no clear designation of duties, creating an ambiguous situation in which ill-prepared municipalities were held accountable despite lacking capacity and resources.

According to the nationally-produced rubble plan retroactively prepared for Oaxaca and Chiapas, each stricken town was meant to separate all post-disaster debris, classify it, reuse it (if possible for elaborate infrastructure construction), and send the remainder to temporary disposal sites. Following this, the leftover rubble was to be moved to one of the officially predetermined, permanent landfills. The rubble was to be treated and sprayed with water constantly to prevent dust from rising and, ultimately, each official landfill was to be turned into a park or other landscape amenity. Perhaps needless to say, there were no municipalities in this low-income region that had the resources, human capital, or physical capacity to handle such an elaborate and costly operation. From a training perspective, practically no one in the country, let alone the region under study, had the capacity to deal with rubble in such a complex manner. Highlighting this, the only facility in the country that is officially certified to deal with rubble is in Mexico City, and it is specifically dedicated to recycling concrete.

The only explicit mention of duties in the nationally-produced rubble plan for Oaxaca and Chiapas indicates that state governments should approve of final disposal sites. Problematically, however, the official responsibility to deal with construction waste and rubble, according to the national Law for Prevention and Integral Management of Waste, actually belongs to municipal authorities.51 In short, the nationally-produced rubble plan instructed the state authority to handle a topic that should be, and generally is, handled by local governments. This confusion led to the three levels of government - national, state and local - simultaneously attempting to coordinate rubble management. However, since all these levels also viewed rubble as a “secondary” concern and not solidly within their area of responsibility and expertise, this also meant that action was as fragmented as it was limited. The lack of role clarity surrounding rubble management was described by an interviewed academic, who stated:

There is a gap in terms of distribution of responsibilities. It is difficult [for municipalities] to act because they usually do not have the necessary resources. There are rules that prohibit municipalities from investing in projects without signing a [formal contract], which makes them accountable for financing and carrying out complex projects in unrealistic times. It is not an efficient mechanism, particularly when it comes to small municipalities.52

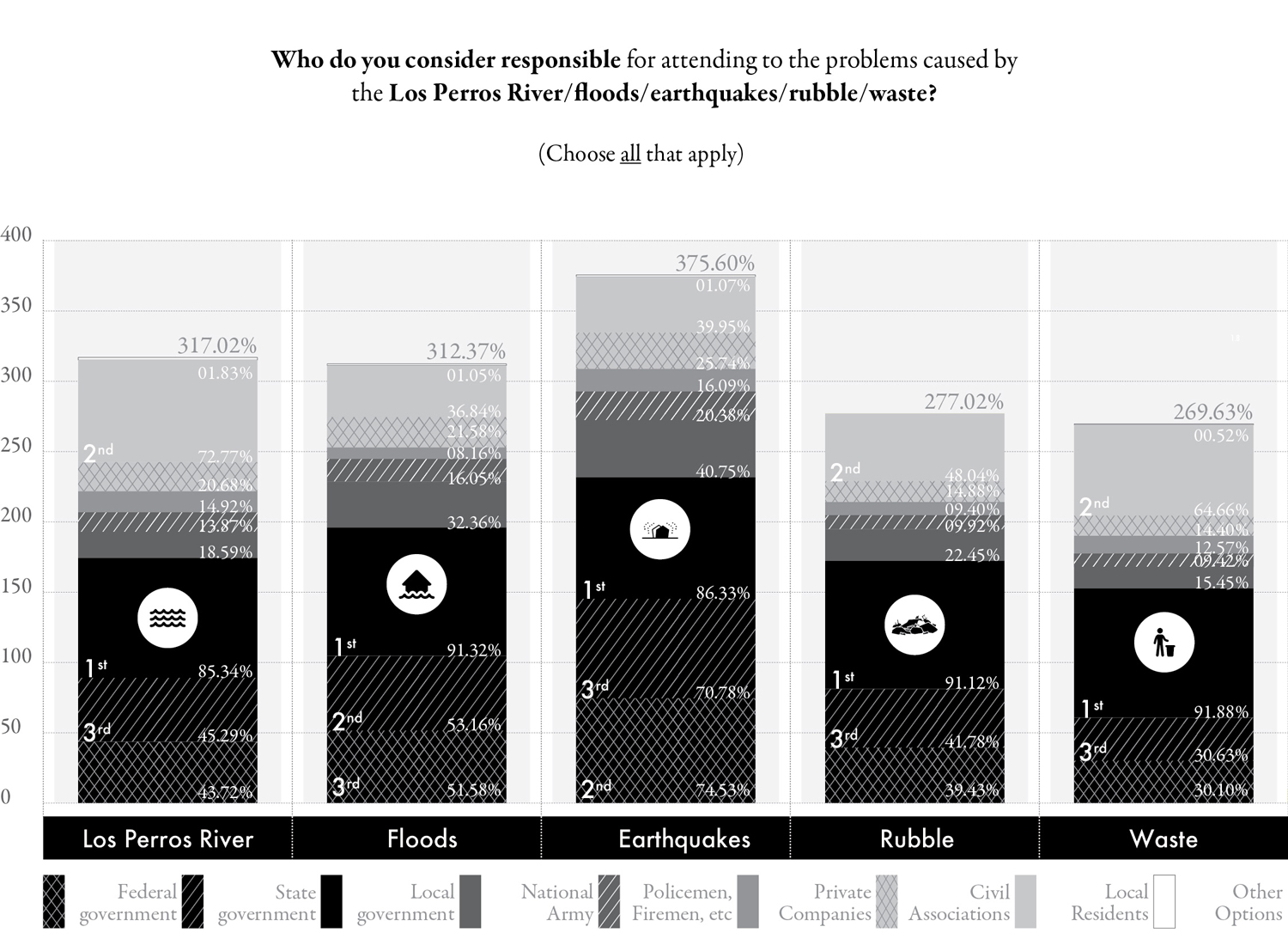

The results strongly supported the sentiment that there was a lack of role clarity around rubble management, and that most actors were unsure of what to do with rubble. This opinion was shared by 57% of interviewees. The idea was also supported by data from the cross-sectional survey, which showed several interesting results. First, the survey showed that only 38% of residents believed rubble should be reused for something other than filling vacant plots or landfills. This suggests there was no clear sense for how rubble might be redeployed to local benefit (Fig. 9).

Interestingly, when comparing respondents’ perceptions of how rubble should be disposed of compared with trash, a much higher percentage felt that trash should be recycled (92% versus 38% for rubble). This difference, combined with the high percentage of respondents who saw rubble merely as a form of “fill,” including for vacant lots, suggests that any hope for a deeper and more productive engagement with rubble may require systemic change and reconceptualization. Second, when asked who they considered responsible for managing rubble, 91% of survey respondents answered the municipal government, making it the most cited entity (Fig. 10). Similarly to rubble management, the number one entity to be held accountable for dealing with broader challenges of risk, including those related to floods, earthquakes, waste management, and river conservation, was also the municipal government (Fig. 10). Notably, municipal governments in Mexico, as in many areas of the Global South, are extremely under-resourced, making it hard for them to act on this perceived responsibility.

Perceived institutional accountability for dealing with problems caused by the Los Perros River, flooding, earthquakes, rubble and waste more broadly. Columns show percent of survey respondents providing each answer. Because respondents could provide more than one answer, column totals are greater than 100 percent

Lastly, all survey participants were asked to rank the institutions engaged in post-disaster response and recovery on the basis of their trust in each of them. The results show that government (at all levels), unions, and political parties were the lowest ranked. In contrast, the church, universities, and other educational institutions were ranked as the most trustworthy (Fig. 11).

The potential implications of these findings, as well as the others reported above, will be discussed in the following section.

Institutions ranked by level of trust assigned by local residents. Values are averages for each institution type, which were scored by each of 384 survey respondents on a scale from -2 (least trustworthy) to 2 (most trustworthy). The column for universities is highlighted in black as this institutional category plays a key role in the paper’s discussion and in considerations about how to develop better rubble plans.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study have a number of important implications for disaster planning in Mexico and other areas of the Global South. First, they demonstrate that a lack of local specificity and contextualization in plans can lead to fragmented and uncoordinated action, which can leave affected cities and regions unable to adequately recover from disaster. In the case of Mexico, the clearest example of how national plans failed to respond to local contexts was the creation, for very distinct geographies, of virtually identical plans to address rubble from the 2017 earthquakes. The finding that virtually identical plans were prepared for these extremely divergent contexts can be understood through the concept of isomorphism, which describes instances where there is homogeneity of organizational forms and processes.53 DiMaggio and Powell argue that the lens of isomorphism can be used to understand the practices of organizations and professions, particularly when they face situations with significant levels of uncertainty.54 As in many other post-disaster settings, uncertainty was a defining feature of the study area following the 2017 earthquakes. Hence, conditions were well-suited to fostering processes of institutional isomorphism, particularly in the case of plans developed retroactively to handle the immense amount of rubble that inundated the region.

In their classic work on isomorphism, DiMaggio and Powell describe three forms of institutional isomorphism: coercive, mimetic, and normative. The first two of these appear deeply relevant to the context of post-disaster rubble planning and action in Oaxaca. DiMaggio and Powell argue that coercive isomorphism “results from both formal and informal pressures exerted on organizations by other organizations upon which they are dependent and by cultural expectations in the society within which organizations function.” 55

In the context of Mexican post-disaster planning, it can be seen that strong expectations about what constitutes a legitimate plan exert a very strong role in shaping the nature, content, and even design of resulting planning documents. The power of this need for conformity is evidenced by the exact copying of larger and more powerful states’ plans, from content to cover design. This pattern of isomorphism mirrors those found in other studies, which show that in highly bureaucratized states, such as Mexico, organizational structures can come to reproduce norms and rules that are seen as legitimate by powerful agencies and decision makers within the state.56 Scholarship on coercive isomorphism additionally argues that the practices of organizations can not only become dominated by concerns around legitimacy, but can also become disconnected from the constraints of on-the-ground implementation and local realities. In this sense, the idea of coercive isomorphism appears highly relevant to understanding post-disaster rubble management in Oaxaca.

In addition to coercive isomorphism, the concept of mimetic isomorphism also appears highly relevant to the findings of this study. Mimetic isomorphism involves the modeling of practices, and it is particularly common in conditions of uncertainty. Building on the work of March and Olsen, DiMaggio and Powell argue that “when organizational technologies are poorly understood...when goals are ambiguous, or when the environment creates symbolic uncertainty, organizations may model themselves on other organizations.” 57 Under conditions of uncertainty, mimetic isomorphism can bring considerable benefits for those making decisions. Not only can such modeling be efficient, generating relatively rapid responses with a limited expenditure of time and resources, but those doing the modeling can also be more confident that the outcomes will meet the expectations of those sharing similar organizational roles.

Thus, both mimetic and coercive isomorphism likely help explain the retroactive proliferation of virtually identical plans for rubble clearance that responded solely to the concerns and normative expectations of central government officials and which were largely, if not completely, disconnected from the needs and contextual details of the local sites in question. Given that little has changed post-disaster with regard to the institutions engaged in response and recovery, it is likely that future plans will continue to lack the local specificity and nuance that would be required to effectively address the needs of these under-resourced environments. As long as plans are developed with a view to securing legitimacy, and focus on emulating plans developed for Mexico City rather than responding to local conditions, it is unlikely that future disasters and their rubble will be addressed any more effectively.

Another important finding of this study relates to the fragmentation and lack of coordination across levels of government. This is problematic because it can exclude potentially important actors from recovery processes, as was shown in the case of plans for rubble management in Oaxaca. These local actors include community members and local organizations, who should arguably be significant players in the development and implementation of post-disaster plans. This is particularly true since, as mentioned, ostensible authority for rubble management in Mexico is officially held by municipal level agencies. In contrast with the increasing presence of the federal government in the creation and execution of post-disaster plans, the results show a growing need to put forward models that strengthen local response capacity, draw on and build local risk awareness, and allow disaster-prone municipalities to use recovery periods as critical, bottom-up learning moments to better cope with future disasters. The findings suggest that it is vital to understand the role of local authorities, residents, and institutions, which were systematically downplayed in post-disaster rubble planning in Oaxaca. Therefore, a shift is needed in which federal resources are channeled to providing the necessary tools for local and regional actors to deal with and learn from moments of crisis. Among other things, this would require improving links between stakeholders and expanding training and capacity building. In other words, disaster governance structures should not only create seemingly efficient, nationally-produced plans but also support decentralized capacity building for residents, local governments, and other institutions to develop contextually-aware, locally-driven prevention and recovery plans and strategies.

The findings of this study also show that a failure to recognize the interconnectedness of vulnerabilities can result in narrow-sighted plans that perpetuate and prioritize a reactive approach to disaster response. Such failure can also lead to local actions that, in their efforts to address one problem, such as rubble, create others, such as pollution or flooding. This was the case in the study area, where disposal of rubble in unofficial landfills led to pollution and created new environmental hazards. This is a stark contrast to the kind of contextualized, comprehensive, and preemptive planning approach advocated by many scholars, including Daly et al.58 Local capacity building would be essential to improving the ability of decision makers and residents in Oaxaca to cope with the impacts of disasters. Such capacity building would not only enhance local skills but also increase awareness that disaster-related vulnerabilities are related and can exacerbate each other. This is particularly true when it comes to issues of rubble management.

As the results indicate, and as evidenced by the large, unsecured landfill constructed by one local mayor, there is a significant gap in understanding regarding the relationship between rubble management and concerns such as environmental degradation, public health, and flooding. Plans to address these seemingly divergent issues could, with appropriate capacity building and learning from more successful efforts - such as the Citizens Disaster Response Network in the Philippines and Project Lyttelton in New Zealand - enable a more integrated and bottom-up approach.59 In other words, one potentially important way to move forward may be to implement vulnerability reduction and capacity building efforts that consciously address rubble and other environmental and urban issues in a contextually-nuanced and inter-related manner.

The results reveal that local people had very different perceptions of the trustworthiness of the different institutions engaged in post-disaster response and recovery. This is relevant because trust has been shown to be important to successful implementation of post-disaster plans.60 As shown by the survey results, one of the possible explanations for the failures in implementation of rubble management plans in Oaxaca was their highly-centralized nature and the prominent role of central government in their development and promotion. The widespread distrust of political actors, including political parties and all levels of government, likely influenced residents’ perceptions of these plans and negatively affected their outcomes. Importantly, however, the results also suggest that several stakeholders were viewed as particularly trustworthy. These groups - including universities, other educational institutions, and civil society organizations - were not heavily involved in the development of existing plans. However, the results suggest that plans developed and implemented with their involvement may be better received by local people and have a greater likelihood of successful implementation.

The findings discussed thus far, which show a pattern of top-down, locally-unresponsive plan development, raise the question of how the status quo approach to post-disaster response, and particularly rubble management, might be changed for the better. Given that the existing approach is embedded in the planning norms of central government, it is worthwhile to consider the issue of norms in greater detail. One idea that could be particularly important in improving rubble plans in Oaxaca, and similar regions of the Global South, is that of the “norm cascade.” According to Finnemore and Sikkink, norm cascades occur when “agreement among a critical mass of actors on some emergent norm can create a tipping point after which agreement becomes widespread.” 61 Considering the potential importance of both coercive and mimetic isomorphism described earlier, a transition to a new normative model for shaping disaster response in under-resourced and marginalized regions, such as Oaxaca, appears all the more essential.

According to Finnemore and Sikkink’s norm cascade model, when a new tipping point is reached new norms can be adopted and promulgated. To effect such a change, they argue that an epistemic leader can serve as an early first mover in adopting and promoting new modes of practice. Such a first mover should ideally enjoy strong trust and support from diverse actors. As the results of this study show, universities would be an ideal candidate to play this role in the Mexican context. This study suggests that having universities involved in capacity building and planning work with local communities could help to both build their capacity and ensure the successful revision of current planning practices. Such efforts would likely enjoy a degree of normative acceptance by a broad swath of actors at the local and national levels. By drawing on universities as a key epistemic player in the post-disaster institutional ecosystem, a new norm cascade might be initiated that leads to plans that are more responsive to local conditions and which benefit local actors through their capacity to connect them with broader resources and scales of action.

Returning to the issue of isomorphism, which we argued was a probable force in entrenching top-down and locally-decontextualized planning norms concerning post-disaster rubble management, DiMaggio and Powell argue that intersectoral coordination can help to override such tendencies towards homogenization. They state that, “to the extent that pluralism is a guiding value in public policy deliberations, we need to discover new forms of intersectoral coordination that will encourage diversification rather than hastening homogenization.” 62 This idea of intersectoral coordination supports the possibility that new partnerships between the state and locally-trusted stakeholders could help to implement plans that integrate bottom-up knowledge and action with a top-down provision of resources and support. To this end, there is a pressing need to create new horizontal and vertical networks, connecting diverse organizations within and across scales. In creating such networks, the fact that some organizations were identified consistently as more trustworthy than others can help to inform who might play a pivotal role in these efforts. In particular, the high trustworthiness of universities, as mentioned, could make them a highly effective player in organizing and mediating such collaborations and engagements across scales.

CONCLUSION

This article examines the factors influencing the response to the 2017 earthquakes in Mexico, with a particular focus on the challenge of rubble management in the Los Perros River corridor in the state of Oaxaca. It draws on an analysis of fifty-one interviews with actors from diverse scales and sectors, as well as a survey of 384 residents and a mapping analysis. Recognizing that rubble planning is limited in many areas of the Global South, the article responds to the call for more information on how rubble is addressed following disasters and, in particular, on cases where environmental standards for dealing with debris are significantly reduced.63

The study reveals five main findings. First, despite the recurrent nature of disasters, plans for addressing rubble in Mexico were created retroactively, prioritizing reaction and short-term action instead of prevention and long-term planning. Second, national disaster response plans were conceived with large cities in mind, despite the prevalence of small disaster-prone municipalities and rural areas. Third, fragmented post-disaster action emphasized municipal boundaries rather than a regional understanding of the affected territories. Fourth, plans ignored economic incentives, creating new market dynamics in which profits, resources, and knowledge went to the highest bidder. Finally, rubble management plans had no clear designation of duties, creating an ambiguous situation in which ill-prepared municipalities were held accountable despite lacking capacity and resources.

To understand these results, the paper draws on several relevant concepts. First, it argues that institutional isomorphism may have played a powerful role in shaping the form and content of nationally-produced rubble plans. In response, the paper argues that greater inclusion of local stakeholders in the development and implementation of rubble plans is essential. To develop new norms that are more locally-responsive, the paper draws on the idea of “norm cascades,” which could potentially be deployed to change the normative conditions in which certain planning approaches are viewed as legitimate. In particular, it suggests that universities, which emerge as widely trusted institutions in the post-disaster context, may play a pivotal role in helping to initiate such changes and in building bridges between planning actors at different scales. Importantly, Oaxaca and the Los Perros River corridor are only one of many places in the Global South experiencing top-down, fragmented, and de-contextualized approaches to post-disaster rubble planning. Indeed, notwithstanding the challenges identified in this study, the InterAmerican Development Bank has ranked Mexico as having created the most favorable governance conditions for disaster risk management in Latin America and the Caribbean.64 This ranking is based in part on the policies the country has adopted since the 1985 Mexico City earthquake. This suggests the remarkable level of risk facing other countries in the region. It is hoped that the lessons from this case may be beneficial in these other related contexts as well.

Maarten K. Van Aalst, “The Impacts of Climate Change on the Risk of Natural Disasters: The Impacts of Climate Change on The Risk of Natural Disasters,” Disasters 30, no. 1 (March 2006): 5–18.

Danan Gu, Patrick Gerland, François Pelletier, and Barney Cohen, “Risk of Exposure and Vulnerability to Natural Disasters at the City Level: A Global Overview,” Population Division Technical Paper, no. 2 (2015).

W. J. Wouter Botzen, Olivier Deschenes, and Mark Sanders, “The Economic Impacts of Natural Disasters: A Review of Models and Empirical Studies,” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13, no. 2 (August 1, 2019): 167–88.

Charlotte Brown, Mark Milke, and Erica Seville, “Disaster Waste Management: A Review Article,” Waste Management 31, no. 6 (2011): 1085–98.

Patrick Daly et al., “Situating Local Stakeholders within National Disaster Governance Structures: Rebuilding Urban Neighbourhoods Following the 2015 Nepal Earthquake,” Environment and Urbanization 29, no. 2 (2017): 403–24.

The Los Perros River (the river of the dogs) is most commonly referred to as the Las Nutrias River (the river of the otters) by local residents. This resulted from an error in translation from Zapotec, the indigenuos language, to Spanish. Its original name, Guiigui’ Bi’cunisa is literally transalted as river of the swimming dogs (otters, in Zapotec).

Lawrence Vale and T Campanella, The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005); Rosetta Elkin and Jesse Keenan, “Retreat or Rebuild: Exploring Geographic Retreat in Humanitarian Practices in Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Strategies to Coastal Communities,” in Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Strategies for Coastal Communities, ed. Walter Leal Filho (Cham, Switz.: Spring International Publishing, 2018).

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Natural Disasters,” OurWorldInData.org, 2020, retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/natural-disasters; Muh Marfai, Andung Sekaranom, and Philip Ward, “Community Responses and Adaptation Strategies Toward Flood Hazard in Jakarta, Indonesia,” Natural Hazards 75, no. 2 (2015): 1127–44.

Michael Hooper, “When Diverse Norms Meet Weak Plans: The Organizational Dynamics of Urban Rubble Clearance in Post-Earthquake Haiti,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research [forthcoming] (2018).

Brown, Milke, and Seville, “Disaster Waste Management.”

Hooper, “When Diverse Norms.”

Martin Bjerregaard, “Who Cleans up after Hurricanes, Earthquakes and War?,” interview by Lucy Rodgers, BBC News, October 20, 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-d7bc8641-9c98-46e7-9154-9dd6c5f....

Rodgers, “Who Cleans up after Hurricanes.”

Brown, Milke, and Seville, “Disaster Waste Management.”

Ibid.

Gabriela Estrada-Díaz, “Prevenir riesgos o atender desastres en las ciudades. Dos opciones de política con alcances distintos,” Trace. Travaux et recherches dans les Amériques du Centre, no. 56 (December 1, 2009): 41–56; Jesús Manuel Macías, “Necesidades existentes para legislar con el propósito de reducir,” in Legislar Para Reducir Desastres (Mexico City: CIESAS, 1999).

CONEVAL, “Informe de Medición de Pobreza,” Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL), 2017.

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo en México, Índice de Desarrollo Humano Para Las Entidades Federativas, Mexico 2015, Avance Continuo, Diferencias Persistentes, February 2015.

INEGI, “Encuesta Intercensal 2015,” National Institute of Geography and Statistics, 2015.

INEGI, Oaxaca. Hablantes de lengua indígena. Perfil sociodemográfico. XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda, 1990. INEGI, 1995; Isabel Castillo, “¿Qué lenguas indígenas hay en Oaxaca?” Lifeder (blog), August 10, 2017, https://www.lifeder.com/lenguas-indigenas-oaxaca/.

Comision Federal de Electricidad. “Manual de Diseño de Obras Civiles (Diseño Por Sismo) de La Comisión Federal de Electricidad,” n.d.

John Rafferty, “Soil Liquefaction - Geology,” Encyclopedia Britannica. As defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica, soil liquefaction is “ground failure or loss of strength that causes otherwise solid soil to behave temporarily as a viscous liquid.” Moreover, “the phenomenon occurs in water-saturated unconsolidated soils affected by seismic S waves (secondary waves), which cause ground vibrations during earthquakes,” https://www.britannica.com/science/soil-liquefaction.

Miguel García, “Vientos en Oaxaca alcazarían 200 kph y tiran tráileres,” El Universal, January 29, 2018, http://oaxaca.eluniversal.com.mx/municipios/29-01-2018/vientos-en-oaxaca....

SEDATU, “Censo de Viviendas Dañadas Por Los Sismos Del Mes de Septiembre de 2017,” 2018; INEGI, “Encuesta Intercensal 2015.” National Institute of Geography and Statistics, 2015.

Redacción, “Terremoto de Magnitud 8,2, El Mayor En Un Siglo, Sacude El Suroeste de México, Deja al Menos 61 Muertos y Miles de Afectados,” BBC, October 12, 2017,

Servicio Sismológico Nacional,“SSN - Detalle de Sismo Seleccionado | UNAM, México,” Servicio Sismológico Nacional, n.d. http://www2.ssn.unam.mx:8080/sismos-fuertes/.

Redacción, “Cuán Preparada Estaba La Infraestructura de México Para Soportar El Impacto Del Terremoto Más Fuerte Del Último Siglo,” BBC, September 9, 2017,

Salvador Sigüenza Orozco, “Oaxaca. Los eternos segundos de una sismicidad histórica,” Relatos e Historias en México, November 17, 2017, https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/oaxaca-los-eternos-segun....

Roberto Ariel Abeldaño Zuñiga and Sonia López Hernández. “La prensa y la participación social frente a los desastres: desde el sismo de Oaxaca de 1787 al sismo de Tehuantepec de 2017,” Revista de Salud Pública 23, no. 2 (June 2019): 94–106.

SEDATU, “Censo de Viviendas Dañadas”; INEGI, “Encuesta Intercensal 2015.”

SEDATU, “Censo de Viviendas Dañadas.”

The results of the broader investigation are publicly available in https://www.bicheechediidxa.com/.

Brown, Milke, and Seville, “Disaster Waste Management,” 1085-98.

Interview with federal official by lead project researchers, July 5, 2018, Mexico.

Interview with local resident by lead project researchers, May 25, 2018, Oaxaca.

J. Eugene Haas, Robert William Kates, and Martyn J. Bowden, Reconstruction Following Disaster, “ MIT Press Environmental Studies” series (Cambridge MA, USA: MIT Press, 1977).

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos, “Firman Sedatu y Semarnat convenio para que remoción de escombros no afecte al medio ambiente,” Government of Mexico gob.mx, September 20, 2017, http://www.gob.mx/semarnat/prensa/firman-sedatu-y-semarnat-convenio-para....

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, “Criterios para el manejo de los residuos de construcción y demolición generados por el sismo en los estados de Oaxaca y Chiapas,” Government of Mexico gob.mx, November 6, 2017. http://www.gob.mx/semarnat/documentos/criterios-para-el-manejo-de-los-re....

Interview with mayor of Ciudad Ixtaltepec by lead project researchers, May 25, 2018, Oaxaca.

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, “Criterios para el manejo.”

Interview with federal official by lead project researchers, July 5, 2018, Mexico.

Interview with state official by lead project researchers, August 20, 2018, Oaxaca.

Interview with local resident by lead project researchers, May 24, 2018. Oaxaca.

Banco del Bienestar, Sociedad Nacional de Crédito, Institución de Banca de Desarrollo, “Refrenda Bansefi compromiso de entregar tarjetas con apoyos Fonden a todas las personas censadas en Oaxaca y Chiapas,” Gobierno de México, October 29, 2017.

http://www.gob.mx/bancodelbienestar/articulos/refrenda-bansefi-compromis....

As converted using xe.com on June 21, 2019.

As converted using xe.com on November 7, 2019.

As converted using xe.com on June 21, 2019.

Interview with local resident by lead project researchers, June 5, 2018, Oaxaca.

As converted using xe.com on November 7, 2019.

“Pagan Mil 185 Pesos Por Retirar Escombros de Casas En Oaxaca,” Excelsior, October 13, 2017, https://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/2017/10/03/1192379.

“Ley General para la Prevención y Gestión Integral de los Residuos,” Diarios Oficial de la Federacion, October 8, 2013: 53.

Academic expert. Interview by lead project researchers. June 11, 2018. Mexico.

Paul J. DiMaggio and Walter W. Powell, “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields,” American Sociological Review 48, no. 2 (1983): 147–60, https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

John W. Meyer and Brian Rowan, “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony,” American Journal of Sociology 83 (n.d.): 340–63. See also DiMaggio and Powell, “The Iron Cage.”.

DiMaggio and Powell, “The Iron Cage.”

John W. Meyer and Brian Rowan, “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony,” American Journal of Sociology 83 (September 1977): 340–63.

Meyer and Rowan, “Institutionalized Organizations.”

Daly et al., “Situating Local Stakeholders.”

Greg Bankoff and Dorothea Hilhorst, “The Politics of Risk in the Philippines: Comparing State and NGO Perceptions of Disaster Management,” Disasters 33, no. 4 (2009): 686–704, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01104.x; Raven Cretney, “Local Responses to Disaster: The Value of Community Led Post Disaster Response Action in a Resilience Framework,” Disaster Prevention and Management 25, no. 1 (2016): 27–40.

Daniel P. Aldrich, “Fixing Recovery: Social Capital in Post-Crisis Resilience,” Journal of Homeland Security 6 (June 2010): 1–10.

Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change,” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 887–917,

DiMaggio and Powell, “The Iron Cage.”

Brown, Milke, and Seville, “Disaster Waste Management.”

Roberto Guerrero, “What Mexico did to Reduce 80% of its Disaster-Related Deaths,” Iadb.org, October 13, 2017, https://blogs.iadb.org/sostenibilidad/en/como-hizo-mexico-para-reducir-e...

This study was sponsored by diverse funds from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, including the Penny White Project Fund, the International Community Service Fellowship, and the Mexican Cities Initiative. Moreover, it received financial support from the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, the National Fund for Culture and the Arts (FONCA), the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT), Fundación México en Harvard A.C. (FMH), Bank of Mexico, and Aeromexico. It is the product of a close collaboration between the investigators and the members of each stricken community, as well as professors, students, and members from other allied institutions. This study stems from a master’s thesis project at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, undertaken by the first author and advised by the second. This resulting paper was written by both authors.

Figure 1: map by © Dení López and Betzabe Valdés, licensed under CC BY 4.0, as redrawn from Comisión Federal de Electricidad, Manual de Diseño de Obras Civiles – Diseño por Sismo (Mexico: 2008).

Figure 2: map by © Nadyeli Quiroz Radaelli, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3: diagram by © Betzabe Valdés and Dení López, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4: photo by © Dení López, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5: photos and graphics by © Dení López, Betzabe Valdés, and Nadyeli Quiroz Radaelli, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6: (a) photo by © Dení López licensed under CC BY 4.0; (b) photo by © Isador licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 7: photo by © Dení López, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8: photos by © Dení López, Betzabe Valdés, and Nadyeli Quiroz Radaelli, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9-11: graphs by © Dení López and Betzabe Valdés, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Dení López is a PhD student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning. Her research focuses on recovery plans and cross-scalar governance in marginalized communities prone to socio-environmental threats. She holds a Master in Design Studies (Risk and Resilience) and a Master of Architecture in Urban Design from Harvard University, as well as a Bachelor of Architecture from the National Autonomous University of Mexico. E-mail: deni@mit.edu

Michael Hooper is an Associate Professor of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia. He previously taught at Harvard University and worked with the United Nations Development Programme. His research focuses on the politics of housing, land use and urbanization, with particular interest in four related themes: displacement, disasters, spatial transformation and participatory planning.

Email: michael.hooper@ubc.ca