Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Aldo Rossi and the Spirit of Architecture

By Diane Y. F. Ghirardo

London: Yale University Press

254 mm x 203 mm

135 color + 5 b/w illustrations

280 pages

US$65 / £50.00 GBP (hardback)

ISBN: 978-0300234930

The first surprising quality of the book is the deep understanding that the American historian and theorist Diane Ghirardo shows towards an enigmatic and quintessentially European architect like Aldo Rossi. Perhaps more than others, Rossi organically reinterpreted the values of the second half of the twentieth century, and not only used them as the foundation of his architecture but, following on the steps of a few “masters” and along with some colleagues, inaugurated a theoretical reflection similar to the one undertaken by other important figures of the past in periods of crisis.

Two core issues, both deply embedded in the European and particularly Italian culture, constantly emerge in the work of Aldo Rossi. Diane Ghirardo enlightens them with particular precision and clarity: the relationship with history, a part of Europeans’ own genetic heritage, and with the city, and the cities of history of which everyone is inevitably heir and continuator.

The European modern age started in the eighteenth century, when cities developed along and around their Roman, Medieval and Renaissance cores. Italian architects grow and develop their works within such issues, implicitly inherent in their culture – they necessarily confront and address them in their work. At the same time, the relationships with history and the cities are also, I believe, the grounds on which European culture most deeply diverges from American culture that, if anything, appropriated them through education. In this respect, Ghirardo’s ability to understand, supported by her explicit and full concurrence with Aldo Rossi’s idea of architecture, is as admirable as the ocean that separates Old and New world is vast.

The second, clear, quality of the book is the absolute documentary precision with which, for each work and architecture, Diane Ghirardo evokes the situation and atmosphere that generated it by reporting facts and backgrounds of each work or thought. Even in this respect, she interpreted the attitude with which Rossi never considered facts individually and instead contextualized them within a precise time and place. This demanding interpretation effort almost sounds as a challenge to her very arguments that rightfully insist on the almost unfathomable but inseparable poetic, expressive and biographical aspect in Rossi’s work.

Many Europeans like me, a Milan-based architect and theorist of a later generation, who, without being his direct student, attended his lectures at the schools of Milan and Venice and trained within the Tendenza, will find this remarkably important research even more interesting for one additional reason: its assessment of how his work was received and considered overseas.

As it is well known, there is a wealth of theoretical essays and monographs about Aldo Rossi, very well documented and partially published while he was still alive. These works represent the fundamental reference for the study and understanding of his work. In addition, there are several monographs about individual works, theoretical writings that consider certain aspects of his thought, as well as even more valuable and enlightening short texts written by friends and colleagues.

A wide-ranging treatment, aimed at providing a comprehensive reading of his work and thought, and establishing constant relations between the two components mentioned above, is quite more difficult to find. I believe this is precisely what Diane Ghirardo’s work offers: an ambition to frame and systematize such a wide-ranging, deep and complex thought, in the pursuit of a balance between the poetic and the rational interpretations of Rossi’s work – two aspects that must be considered jontly, otherwise his work fails to provide its fullest sense. I believe Ghirardo enjoyed a remarkable advantage in addressing such a challenge, given her point of view at the same time detached and very close (due to her personal acquaintance with Aldo Rossi), as well as her ability to read many texts, written either by himself or by others, in Italian.

Diane Ghirardo provides a wealth of arguments. I will only pinpoint the more general ones, which are particularly valuable for the book, as they successfully frame Rossi’s work by providing materials for further study and discussion.

First of all, I would like to underline a reading key that subtly runs across the entire book and immediately conjures the fascination and complexity of Aldo Rossi’s world. This is the recurring proposition of a series of dichotomies, oppositions and dualities that characterize his work in terms of apparent, sometimes confusing, always problematic contradictions. As Ghirardo implies, they are certainly mutually necessary as well as invariably solved and reconciled within his designs. Some are more evident and substantial than others for those who are interested in his lessons: the pursuit of a scientific quality in design and of a poetic quality in the works; a firmly rational position and the pursuit of architecture’s expressive quality; the firm anchoring in reality as a rooting ground and the use of imagination as an essential tool for artistic production. As Ghirardo underlines, science and art, reason and expression are simultaneous and indispensable aspects in every architecture for Rossi. In this sense, he clearly emerges as an heir of Étienne-Louis Boullée, whose treatise (Architecture, essai sur l’art, 1780s, first publ. 1953) he translated and published into Italian (Marsilio, 1977). Boullée was the “visionary architect” of the French Enlightenment (a definition coined by Emil Kaufmann), himself a re-founder of an idea of architecture viewed as art, in the late eighteenth century, an age of stylistic confusion when the worlds of knowledge were claimed as unified and pacified.

Aldo Rossi had another, more direct and contemporary master to whom I believe he was deeply indebted. Although Diane Ghirardo mentions him without further insistence, I think this aspect would deserve an additional treatment. Ernesto Nathan Rogers, the Editor-in-Chief of Casabella - Continuità during the post-war years, was a master as he argued that the construction of the world is a dialectic process developed by synthesis of opposing elements. He also encouraged his young collaborators, including Rossi, at the magazine’s Research Center, to explore the reasons of architecture, to meditate on method, to study the scientific tools of design, to consider it as an art made by human beings for human beings. As a rationalist architect and member of the CIAM, Rogers did so mainly to overcome the functionalist impoverishment perpetrated by the International Style. He should also be credited for introducing the issue of continuity, for encouraging the revival of history in Italian architecture - see the harsh controversy with Reyner Banham about the Velasca Tower in Milan, completed in 1958, and the alleged “Italian retreat” from modern architecture, waged from the pages of the Architectural Review 747, April 1959. With remarkable autonomy, new depth and creative genius, Rossi appropriated this issue in his own architecture. The relationship that Aldo Rossi’s architectures newly established with history is precisely one of the main themes in Diane Ghirardo’s interpretation of his works.

The book comprises seven illustrated chapters, as well as a valuable set of appendixes. Besides the long and precise notes, such appendixes include an accurate chronology of the works produced between 1959 and 1997 (a quite generous record despite Rossi’s untimely passing), as well as a wisely selected bibliography given the vast production of writings by and about him.

After a short “Preface” and the customary acknowledgements, Ghirardo offers “A Brief Biography” that, following on the steps of the “scientific auto-biography” of his master and friend, retraces Rossi’s thought and itinerary of studies and research rather than his life. Besides listing facts and events, such an original interpretation establishes relationships among events and thoughts, education and life, ideas and works, masters and inspirations.

The following two chapters address two fundamental questions. The first, in “Architecture and the City,” is the relationship between the two terms that, in a different formulation (The Architecture of the City, 1966) provide the title of Aldo Rossi’s famous book, or rather treatise, first translated into English by Diane Ghirardo herself in 1982, with an introduction by Peter Eisenman. The second question is the relationship with history, or perhaps, we may say, with one of its more private and personal forms, a tool to trigger history, memory.

The third chapter, “Memory and Monument,” introduces another important concept presented in Rossi’s treatise: the role of the monument in the construction of the city. Besides the common etymology originating from Latin, Diane Ghirado compares the two terms in order to address the key issue of the identity of places, something the monument evokes as the interpreter of collective memory. Memory originates from mèmor, the ability to remember, while monument originates from mònere, meaning, again to remember, or to evoke; the suffix mentum refers to the means or the act of remembering. Therefore, once again, a dichotomy between personal memory, which refers to the author’s individuality, and collective memory as the unavoidable civil responsibility of architecture, achieved in completed works.

The three middle chapters present, describe and interpret the body of works.

The architectures are grouped under major themes that obviously highlight their urban meaning and value rather than functionalist intention. “Building for Culture” – as an action and a major and fundamental collective institution – includes schools, libraries and museums; “Rossi and the Theater” addresses theatricality as a key to a large part of Rossi’s idea of architecture (Ghirardo rightfully places the only house presented in the book in this chapter); “Cemeteries for Modena and Rozzano” is a well-deserved tribute to the work in Modena, discussed at length, that earned Rossi – according to Ghirardo – a lifelong world fame.

Rossi’s early housing projects are noticeably absent – from his first housing district, San Rocco, in Monza, to the complex at the Gallaratese district in Milan. The residential blocks he designed in Berlin and Paris, reinterpreted reconstructions or completions of urban blocks, are mentioned in other chapters. However, this theme fails to receive a specific discussion – rather inexplicably, or perhaps because it would have entailed a complex re-reading of the typological tradition of Italian and Lombard housing (courtyards, ballatoio single-corridor housing, and ringhiera housing among others).

The last chapter “Aldo Rossi and the Spirit of Architecture,” has the same title as the book and is a meditation on Rossi’s philosophical thought, his more personal education and his melancholic and at the same time joyful personality – yet another opposition. After a short review of the critical reception of Rossi’s works, Ghirardo once again retraces the key issues in his work by reading them through this filter, and underlining the role of the classical, humanistic and Catholic education of his youth and its influence on his entire artistic production.

The images the author has chosen for the text – mostly stunning and well-printed photographs of completed buildings, from archival and repertory sources – are quite peculiar. Technical drawings, plans, elevations and sections are almost absent – probably due to the more than generous availability of such documents in other publications about the architect. Some of the famous and beautiful sketches Rossi used to produce, even a posteriori, to go back to his designs and better clarify their guiding principles, make an exception. This precise iconographic choice reflects the intention of the book that, rather than documentary, is basically critical and interpretative, deeply involved in the difficult reading of Aldo Rossi’s artistic and poetic contribution.

Ghirardo interprets and discusses many other major issues in Rossi’s work – incidentally, presenting a body of work in problematic terms, by asking questions and looking for answers, is always a great merit. Chief among them is the relationship between architecture and life: an essential, fundamental issue without which architecture would be entirely meaningless, because architecture, as Rossi and Ghirardo equally argue, is the construction, to put it with Rogers, of “the house of man.”

This relationship with life is the key to overcome “naive functionalism,” as Rossi defines it in his treatise, and provide the forms of architecture with meaning and content – what basically makes architecture an art. Architecture is the “fixed scene” of human life. Only in this sense, Ghirardo explains, can architecture find an object of representation, a meaning, a collective and civil value it can manifest in its designs, stage and, precisely, translate into forms. Only inasmuch as architecture is representation, as Boullée argued, it can become art.

Hence, the importance of the theatrical aspect that, as mentioned above, exceeds purely theatrical architectures, deeply loved, studied and boldly experimented by Rossi – as exemplified by the floating Theater of the World. Theatricality must be an inherent quality in all architecture, because architecture “represents” human beings, their values and collectivity. Once again, this appears as a dichotomy singled out by Ghirardo’s reading: a personal view of architecture that, however, aims to become the voice of a collective culture. This is the purpose of the monument, for Rossi a synonym of building for the collectivity: “representing” a shared identity, and reminding us of this identity of ours.

“Bold and ordinary,” the definition of Aldo Rossi’s architecture coined when he received the Pritzker Prize in 1990, recurs several times across the book: bold and ordinary, at the same time cultivated, daring and popular. Antonio Monestiroli offered a similar description in a short essay quoted at the end of book, where he highlighted Rossi’s ability to look at daily reality with an unfailing fascination, to highlight the extraordinary in the ordinary, with the candor of a child and the depth of reason, Ghirardo adds. He was able to produce an apparently simple architecture, immediately understandable in its forms, although intellectually sophisticated and refined, and to speak with a simple language while conveying important meanings.

There was never a more appropriate definition for Aldo Rossi: at the same time, a cultivated and a popular architect, in a certain sense already predestined in his name. In Italy, the name “Rossi” is a metaphor for “anyone” – like “Smith” in the Anglo-American world. “Signor Rossi” is the common man: he is all of us. Only the name makes the individual distinguishable from everyone else. The same is true for Rossi’s architectures, which strive to interpret a general value and are always rooted in a precise place, in a city from which they acquire specific characters and individual qualities.

Diane Ghirardo describes an idea of the world as a constant discovery, a reality that, while revealed through imagination, must still be known in its depth, in its roots, in its history. So, we go back to history and the tools required to explore and get to know it.

The notion of “type” is one of the few that might have deserved further critical analysis in the book, although it would have required a quite large discussion. Still, it is one of the most important lessons Rossi left us, along with others who, since the 1960s, addressed the rational aspects of architecture, the only ones that can be conveyed as the necessary, although not sufficient, foundations of each project. According to Rossi, type is a constant that recurs in history because it is the irreducible core of each building, deeply related to its meaning. As an abstract “structure,” it is related to space and, while still shapeless, can be known through the forms of buildings across history. It provides indications about their meaning and urban role, their abilities to define places, to shape the city and its parts. It is the main scientific tool for the knowledge of the city, an analytic instrument and at the same time, and more importantly, a design tool we can use as a starting point to shape architectures and places.

The concept of type introduces an important distinction in the relationship with history and the use of its forms that Rossi, as Ghirardo underlines in all the architectures she presents, was very interested in. Only this passage through abstract thought enables an analogic reading of history, and allows not to fall into the trap of copying and to establish a productive, precisely analogic relationship, with the architectures of the past. Only by recognizing the general features of a work – and type, along with the connection with urban morphology, is the key feature – it is possible to continue history, or better, to work in the wake of tradition, as Rogers used to argue. This means recognizing what is still alive in the history of our culture and revive it, in other forms and other places, while developing architectures and parts of a city that is still completing itself.

Analogy – Ghirardo insists – has a fundamental role in the thought and work of Aldo Rossi, both in his architectures and in his theory of “the city of parts,” which allows for continuity and guarantees modernity at the same time, and perhaps makes Aldo Rossi’s world of forms so easily and instinctively recognizable. Analogic thought filters memory, chooses and traces a clear boundary between copying and quoting. Finally, it saves from the danger of formalism and it is perhaps the only key to the exercise of an imagination that freely finds the most appropriate correspondence with the meaning of things.

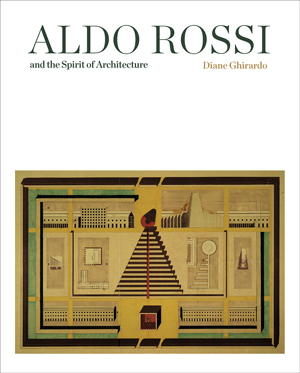

The cover of the book shows a famous drawing of the Cemetery in Modena with a planivolumetric representation, plans and elevations: an entire world in an enclosure. The subtitle of the book is The Spirit of Architecture. For Diane Ghirado, this connection between the cover image and the subtitle was not accidental, I believe.

Raffaella Neri is a Full Professor in Architectural and Urban Composition at the Politecnico in Milano, where she graduated. She is also a member of the Dissertation Supervisory Committee of the PhD program at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura in Venice, where she received her doctoral degree. Her research mainly focuses on architectural theory, particularly on the problem of the “urban project” in the modern city and on the role of construction in architectural design. She published essays on these topics on books, journals and magazines in Italy and internationally. She entered several architectural design competitions. In 1996 she won the National Architectural Prize Luigi Cosenza. E-mail: raffaella.neri@polimi.it