Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

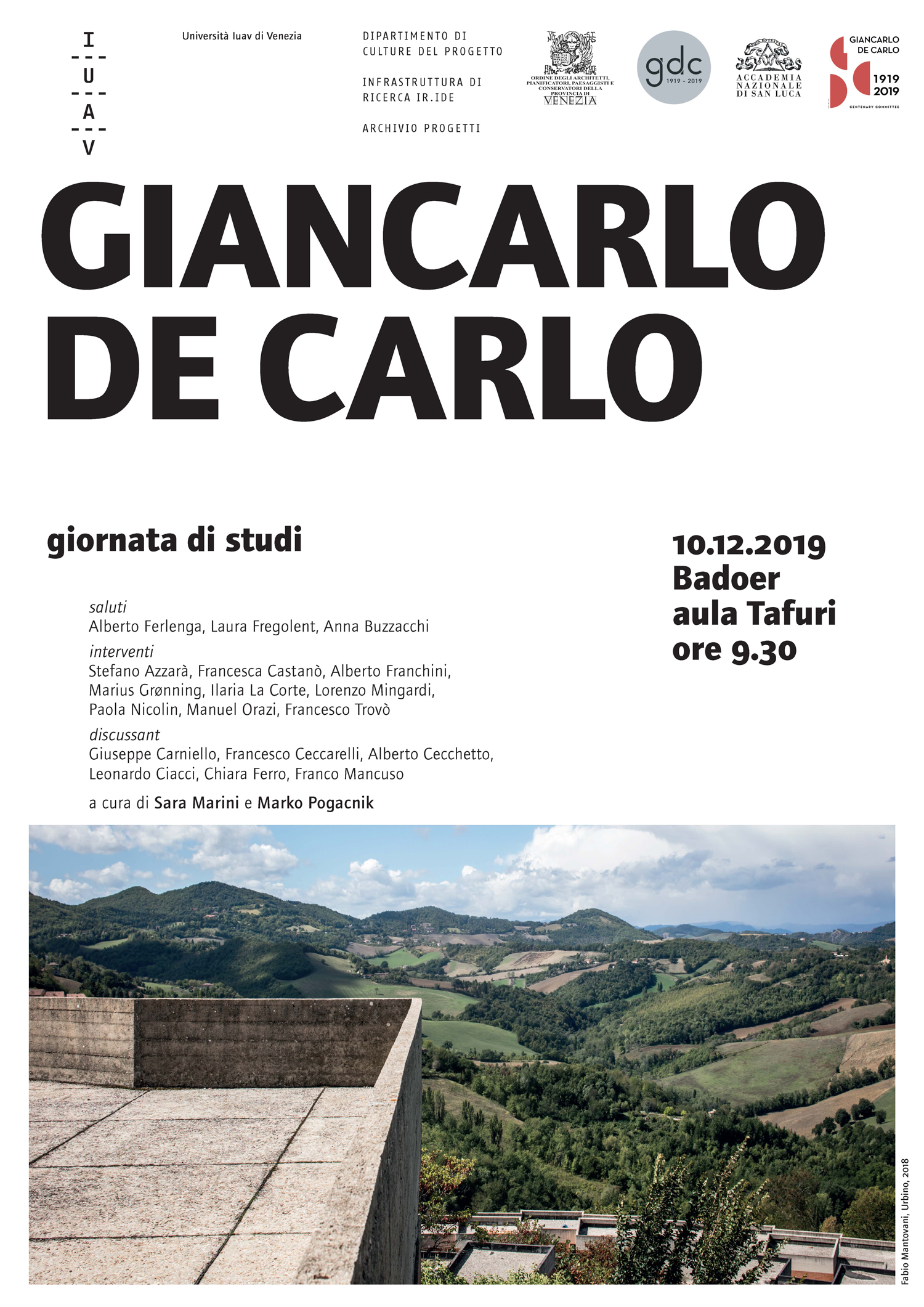

On December 10, 2019, a symposium on Giancarlo De Carlo (GDC) was held at IUAV [Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, Venice, Italy], curated by the authors. The IUAV University, the Department of Architecture and Arts, the Archivio Progetti – holder of the impressive collection relating to De Carlo’s works – the research infrastructure of IR.IDE (of the IUAV Department of Project Cultures), and the Venice chapter of the professional association of Architects, Planners, Landscape Architects, Preservationists of the Province of Venice collaborated to organize the meeting on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of the important Italian architect.

The symposium wanted to return to ongoing investigations into the work of GDC with the objective of opening up new research perspectives. De Carlo’s architecture is a multi-faceted field of work that offers today the possibility to reflect on the role of planners and on the tools at thier disposal to act in a deeply-changing reality.

The ensemble of speeches went through the detailed framework of the methods used by a difficult-to-label author who intended to promote the project as a direct expression of an idea of society. The investigations into the correspondence of GDC, on the writings, preparatory and executed material in the IUAV Archivio Progetti and in other archives, the study of the references to the root of this thought, the direct or remote comparison, carried out through the architectures (also created with other authors), draw a wide field of research. The continuous revision of the critical and design tools utilised by GDC, his communication strategies, the connections between design, teaching and publishing are objects of study and possible research tracks yet to be developed. The published and unpublished documents were material for reflection and discussion, and also the realized architecture, on which we wanted to open a debate, not only raising awareness on them, but also about their protection and preservation.

The symposium was divided into two sections: the first dedicated to the dialogues that GDC had woven into his various decades of activity with other cultural spheres involving design knowledge, such as philosophy, sociology, literature; the second dedicated to the methods and strategies of the Genoese architect and to the prospects that these may open up for contemporary design. Highlighted below are the key passages that emerged from the reports, the order of which follow that one of the presentations.

DIALOGUES AND DISCUSSIONS

GDC in Correspondence

Marko Pogacnik, Professor of History of Architecture at IUAV, initially turned his attention to the critical reception of De Carlo’s work which had hitherto only focused only on individual segments of his biography or built architecture (Urbino, Terni, participation, ILAUD, etc.) without addressing De Carlo’s overall figure. Despite some important contributions in this direction (books by Lamberto Rossi, Benedict Zucchi and John McKean), there is still missing a monograph that describes the jagged path of his intellectual profile, investigating in particular, the moments of crisis. And it is into these moments that the seminar proposed some insights through the readings offered by both the speakers and the invited discussants.

To simplify, we can divide De Carlo’s biography into three major periods, which emerge in the light of two moments of profound rethinking, represented first, by the unsuccessful conclusion of the 1968 Milan Triennale, and the second, by the dissolution of Team X, whose annual meetings stop in the early 1980s.

After the failure of the XIV Milan Triennale, De Carlo abandoned Milan, which had been the city where he trained (with Giuseppe Pagano, Franco Albini, Piero Bottoni, and Ernesto Nathan Rogers, as well as the experience in the Movimento per gli Studi dell’Architettura), to begin a sort of internal exile that will bring him to Venice (where he taught from 1953 to 1983), to Urbino (a city that is “intertwined” with his biography) and Terni (where he realised one of the exemplary works on the theme of participatory design and planning). As also in the case of Siena, Rimini, Genoa or Pavia, De Carlo’s wandering translated into an interpretation of the role of the architect as an interpreter who conceives his professional role as a process of total identification with the city that is home to him/her at that moment. Each assignment, however limited, was an occasion to carry out that exercise of “reading,” and listening to, the urban context, that was the basis of his way of understanding the project. This idea of civil engagement attributed by De Carlo to the work of the architect is perhaps one of the reasons that led him to remain silent (with the exception of the Zigaina and Sichirollo Houses) about the numerous commissions for private houses he undertook over the years. On this aspect, our knowledge has been enriched thanks to the contribution by Francesco Ceccarelli, invited as a discussant, who still lives in the house built by De Carlo for his father on the hills overlooking Bologna.

In the late ‘70s, an extremely productive period, De Carlo began to rethink the foundations of his own language and new themes were added to his work: the idea of breaking free from the constraints of a positivist conception of the structure of a building and the pleasure of studying the effects of a more complex geometry at the basis of the project. From this new phase of his work, there were projects that bear witness, such as the staircase of the Palazzo degli Anziani in Ancona, and the Outlook Tower in Siena, and works such as Blue Moon of the Lido in Venice, and the gateways of San Marino, works on which criticism has until now been expressed with great reservations. De Carlo evoked the image of the relationship between a tree and the creeper that climbs its trunk: “I know very well that it is the tree that holds the creeper up, but you could also look at the creeper from another perspective, as if it had collaborated. And then everything changes.” 1 De Carlo was interested in the relationship between the science and the art of construction, entropy, fractals, the theories of chaos, and on these themes the symposium was able to hear the testimony of another discussant, engineer Giuseppe Carniello, who was his collaborator in the early ‘80s on projects such as the gateways of San Marino.

Having made this long introduction, it is time to return to the theme selected for the first part of the symposium, that of dialogue and discussion, a key to the reading that was interpreted by Pogacnik through the important correspondence of the architect held at the IUAV Archivio Progetti. The epistolary dialogue documents the extensive network of friendships and relationships that Giancarlo De Carlo was able to weave during his long activity. His personal correspondence alone amounts to more than 2,000 papers, to which must be added – because they are ordered separately – the letters relating to his professional work, those written as Editor-in-Chief of Spazio e Società / Space & Society (1978-2001), and, lastly, the correspondence for ILAUD (International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design) - the international school which he directed from 1976 to 2003. To this already significant body of work must be added the correspondence as a member of the MSA (Movimento di Studi per l’Architettura, of which he was Director from 1955 to 1957, a period that coincides with his activity as associate editor at Casabella - Continuità) and of Team X (from the CIAM meeting in Otterlo in 1959 until its disbandment in 1981).

Personal correspondence alone documents the exchange of letters with nearly five hundred and thirty correspondents in a time span from 1957 to 1999. The study of this material has only just begun and of this, it was only possible to give an account through a survey limited to some protagonists (Aldo Rossi, Francesco Dal Co, Denys Lasdun, Giorgio Macchi, Renzo Piano and Bruno Zevi), a survey that, in this seminar, could only briefly illustrate the last of the mentioned figures, Bruno Zevi.

The first letter preserved in the Archive dates back to 1963, the one with which Zevi took his leave from Venice to take up the Chair of History at the University of Rome. De Carlo imprinted his dialogue with his interlocutors by making use of every possible rhetorical device, from harsh accusation to an attempt at explicit seduction, and these different methods were all used in the correspondence with Zevi. Their acquaintance dated back to the years in which the MSA collaborated with the APAO (Associazione per l’architettura organica – Association for Organic Architecture) in an attempt to address the architectural debate that was then developed in magazines such as Metron, Comunità, Casabella and then L’architettura. De Carlo saw in Zevi the figure of a protagonist capable of exercising considerable power thanks to his international relations (with America, UNESCO, and other academic institutions) as well as his position in Italy - Secretary of the INU (Istituto Nazionale di Urbanistica – National Institute for Urbanism), strong relationships with the publishing world, and jury member in many architectural design competitions. Their epistolary relationship – one of the longest and most consistent, with almost sixty letters written from 1963 until 1999 – was characterized by a great asymmetry, in that Zevi (through his magazine L’architettura and other editorial projects) continued his attempts to engage, whereas De Carlo always responded by avoiding to binding a commitment. De Carlo had no confidence in Zevi, and to this, he added a grievance towards him for having hindered him (according to De Carlo) in both his academic career and design competitions. But their distance became profound after the publication of Zevi’s Il linguaggio moderno dell’architettura (1973), in which Zevi attempted to define an anticlassical code of stylistic matrix, as far as possible from De Carlo’s stance, that was based on the idea of complete designer freedom in the field of design research. Nevertheless, through writing and letter correspondence, both seemed wanting to remedy mutual anxieties that converged on a single point: the perception of their progressive isolation in a cultural landscape increasingly linked to the spectacularization of an architecture that is almost exclusively paper-based.

The few surveys that have been carried out on the ample correspondence indicate promising research prospects, as they are not only capable of reconstructing in detail the historical context in which De Carlo’s professional career took place, but also of delineating more precisely his intellectual profile, hitherto described only through his written works.

Livio Sichirollo and GDC. Architecture and Philosophy

Stefano Azzarà, Professor of History of Philosophy at the University of Urbino, underlined how much the experience of De Carlo in Urbino was marked by meeting and collaborating with the philosopher Livio Sichirollo, who in addition to being a professor at the University of Urbino, was also the City Councillor for Urban Planning.

Trained in the climate of Italian neo-idealism, in the cultural ferment and the anxiety of post-WWII renewal, Sichirollo quickly turned to Marxism. It was a peculiar Marxism, however, which according to the typical approach of Italian historical materialism, was strongly imbued with Hegelian thought, a historicist Marxism that was particularly careful to be objective in the idea of concrete civil institutions. Hence Sichirollo’s constant attention, in his studies of dialectics, to the theme of the city and its functions and transformations in the heart of human relationships, with the aim of regulating the collisions present in civil society and of helping to transform a reality in which, otherwise, spontaneity would mostly coincide with the power relations between classes. It is a problematic whose genesis will follow, starting from the thinking of Plato and Aristotle, and which will play an important role in his relationship with De Carlo, and in the common reflections of these two intellectuals on the Urbino Master Plan of 1964.

GDC and the French Urban Sociology Studies

Marius Grønning, Professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) proposed as a line of research the deepening of the links between the thinking of GDC and French sociology. While the Anglo-American references of the Genoese architect are known and often highlighted, reading the magazines Espaces et sociétés and Spazio e Società allows us to reconstruct De Carlo’s relationships with French urban culture.

A common feature of the two voices, those of Lefebvre and De Carlo, is the commitment they express in establishing the foundations of critical thought around the theme of the notion of “space”. The French magazine inspired the birth of the Italian one, even though they are based on two very different disciplinary identities. These observations insist on the theme of “spatial consciousness,” or on the strong link between strategic and political consciousness, professional responsibility and the relationship between space and society. The consultation of the Espaces et sociétés archives in Strasbourg could offer new materials and ideas to reflect on the idea of the city cultivated by De Carlo.

Riccardo Dalisi, at the Origins of Participation

Francesca Castanò, Professor of History of Architecture at the II University of Naples, addressed the origins of participation through the dialogue between Giancarlo De Carlo and Riccardo Dalisi. The correspondence held at the IUAV Archivio Progetti reveals the dense exchanges that took place between them from 1968 to 1972. This is a central period of De Carlo’s activity, in which projects such as the Rimini Master Plan, the Rampa at Urbino, the Matteotti Village in Terni and his reflections on “participation” take shape. The theme, born from the desire to bring architecture back into the environmental scene, listening to physical and social contexts, also involved Dalisi’s research in the same years, as he had not remained idle in this field, involving urban and suburban areas of Naples and the understanding of the consciousness of all classes and ages. Between 1967 and 1970 in the CEP Traiano district, built in the western area of Naples, as part of the Coordinamento per l’Edilizia Popolare (Coordination for Affordable Housing), Dalisi defined a new methodological approach focused on the study of built form as placed in relation to the spontaneous modification of space. This was an approach for which De Carlo expressed a sincere interest.

Among the points of attention that emerged from the epistolary documentation, there are experiments in the field of generative geometry, for which De Carlo praises the introduction of the social variable alongside the canonical spatial-temporal ones: a changed concept of landscape re-interpreted “on the basis of a very opportune demolition of old and new myths.” (Letter from De Carlo to Dalisi, Milan, April 15, 1970). Finally, is the idea of a pervasive and widespread university, or higher educational system, across the city.

On the contrary, the concept of urban disorder, which for Dalisi acquired a metaphysical and aestheticizing value, anchored within a sphere that is still highly theoretical, represented for De Carlo the principle of an alternative creative process to traditional preordained procedures, as an inclusive and participatory design act to be selected and removed from unpredictability. Driven by these analyses, Dalisi shifted his research to an application level through the direct involvement of the children of the district, in an immersive and concrete participatory practice with many effects on the operativity and the vitality that his methods would assume. The Nursery School project that resulted from it, in the absence of conventional planning tools, without a licence, without a construction company, without an area of exact location, takes on the force of a design manifesto that led De Carlo’s “creative disorder” into the territories of utopian radicalism. In the outcome of this imaginative participatory practice, there is perhaps the greatest distance between the two architects and also the last act of their intellectual conversation.

XIV Milan Triennale, 1968. GDC between Italy and the United States

Paola Nicolin, critic, curator and Professor of History of Contemporary Art at the Bocconi University of Milan, focused her attention, through handwritten letters, on the relationships that occurred in 1967 between De Carlo and a community of international artists and architects linked to American culture. At that time, De Carlo was actively involved in the conception and realization of the international exhibition of the “Grande Numero (Big Number)” at the XIV Milan Triennale (1965-68). In relation to this project, De Carlo undertook several trips to the United States where he organized meetings and visits with some leading figures invited to participate in the event, such as Shadrach Woods, Gyorgy Kepes, Fumihiko Maki, Arata Isozaki, Hugh Hardy, Peter and Alison Smithson, George Nelson, Saul Bass, as well as a series of interlocutors linked to the national participation of that edition. In this context, the correspondence between De Carlo and the Executive Board of the Triennale is voluminous, in particular with its Secretary, Tommaso Ferraris, adding details and elements not only to understand De Carlo’s vision, but also the conflicting points of view within the Milanese working group of the exhibition project. In a crucial year for the definition of the assets of Italian institutions, also the Triennale, through this experience, was thinking about the need for a new management form and the sometimes difficult role of the Artistic Director.

The letters are therefore proposed as having a dual role: on the one hand, as a documentary and historical research tool on the project, in support of the importance of correspondence as an element of analysis, on the other, as a chapter in the biography of the Genoese architect, in support of the importance of calligraphy – the style, the medium, the alternation between diary and essay writing, etc. – which was one of De Carlo’s talents as an architect who wrote. Through the discovery of some unpublished documents kept in the Archives of the Milan Triennale, Nicolin’s contribution focused on the reconstruction of the initial phase of the international exhibition, retracing the genealogy of relationships and exchanges that De Carlo built for the Milanese institution and that, because of his employment/occupation and its early closure, have never been made public.

METHODS, STRATEGIES, PERSPECTIVES

“È tempo di girare il cannocchiale” (It’s Time to Turn the Telescope). The 1994 Urbino Master Plan by GDC

Sara Marini, Professor of Architectural and Urban Design at the IUAV, addressed the thorny and forgotten experience of the second Master Plan that GDC signed in 1994 for the City of Urbino. The first Master Plan drafted in 1964 by the same author for the small city of the Marche region has been largely implemented and its impact is therefore tangible, and was also translated into a theoretical-design paradigm in the book Urbino. La storia di una città e il piano della sua evoluzione urbanistica (1966; Engl. ed., 1970 2 ).

On the contrary, the 1994 plan has only been partially translated into reality and the attempt to recount this in a book, as attested by Paolo Spada, who participated in the drafting of the project, was a failure. The last plan by GDC for Urbino was published, or rather, just presented through a series of collected articles in the 102 issue of Urbanistica (1994).3 The failure to implement the plan and the lack of interest in it is attributable to its stance, placing, with great foresight, at the core of the argument, the care for the environment, within a country and a social debate still focused on unconditional urban development.

From 1964 to 1994 De Carlo continued to work on Urbino with ILAUD (International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design). The international laboratory took place from 1971 to 1976, and then from 1992 to 1993, always in this city and using it as an object of study and a design paradigm. Then, in 1976, after a long search, De Carlo finally bought and renovated a house (Ca’ Guerla) in Urbino, or rather, ten km (6.2 mi.) from the historic centre and in the middle of a forest. The house is an outpost, composed of a fifteenth century tower and a farmhouse annexed to it in a later period. In some letters filed in the IUAV Archivio Progetti we read that De Carlo monitored and preserved the environment around the house from misuse or tampering: the value of the Urbino lands will then be the cornerstone of the 1994 Plan.

Between GDC’s first and second Plan, Leonardo Benevolo was commissioned, in 1983, to draw up a new Master Plan for Urbino, which had as its only result the Detailed Plan of La Piantata. It is a dense residential settlement, anomalous within Urbino’s context, due to its lack of theoretical positioning towards the idea of modernity of the city, built beyond the La Pineta neighbourhood that GDC had thought of as the northern gate of the city in 1964. La Pineta, an ensemble made up of three unité d’habitations embedded in the hill, follows the great size of the Ducal Palace and establishes the point beyond which the city should not have expanded, also because of the unsuitable quality of the terrain. La Piantata, built in the 1980s, will then be the subject of GDC’s 1994 Plan: a series of tree planting interventions are planned here in an attempt to reintegrate the densely built-up area into the design of the Urbino landscape.

“È tempo di girare il cannocchiale” (It’s Time to Turn the Telescope) is the title of GDC’s editorial for Spazio e Società 54 (1991). In it GDC wrote: “The environment is everything. […] this means disrupting the one-way interpretative frameworks to replace them with more fluid search modes that can arrive at interpretations and propositions by marking multi-directional, itinerant, erratic paths, more adherent to environmental complexity.” The 1994 Plan precisely represented the implementation of this reversal of the framework: if in 1964 the main object of the plan was the historic centre and the definition of the architectural borders of the city, the 1995 Plan was dedicated to the landscape, anticipating very current issues. It should be noted that the plan was drawn up following the entering into force in 1989 of the Regional Environmental Landscape Plan of the Marche region (the first of its kind in Italy) and therefore GDC’s attention to the environment was also dictated by the tools in the field. However, the intense and heartfelt presentation of the plan (also filed with the IUAV Archive), given in 1994 in the Raffaello Sanzio Theatre in Urbino, reveals how much the author was immersed in this new perspective. The environment, as reiterated in the report, is the combination of the natural context and the activities that take place there: it is a living and productive body, as “narrated” in the backgrounds of Renaissance artworks. The Plan had as its objective this reactivation in response to the depopulation and abandonment of the territory primarily in favour of the Marche coastal system, innervated by national connection infrastructures, and secondly with respect to the concentration of the inhabitants of Urbino in the suburbs built in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s that GDC judged, with the passage of time, all failures.

GDC not only had the courage to bring back into play his own point of view, the themes, the issues, but also his aptitude to design tools that fully adhere to the given spatial-temporal conditions and the set targets. The tools for rebuilding, enhancing, innervating the Urbino landscape with new energies, now an orphan of agricultural activity and that design that made it one with the body of the city, are: the viewing points, the panoramic scenery, and the parks. The latter provides for five variants: the Parco del Foglia e del Pallino, the Parco di San Lorenzo in Cerquetobono, the Parco delle Cesane, the Parco Urbano (Urban Park, today a UNESCO Buffer Zone around the historic centre), the Parco Scientifico (Science Park). The park allocation was to have involved 38 % of the municipal area and foresaw landscape conservation and enhancement interventions, agricultural activities supported by new technology, the creation of residential and craft areas based on the model of the village (Urban Park), and a new University Headquarters in the area with degree courses dedicated to Earth Sciences (Science Park). In practice, all the regional forces – from those more vigorous at the time, such as the university, to those more dormant, such as agriculture and crafts – were addressed in the plan to build a new environmental and economic condition in response to abandonment. Even the planned interventions regarding the infrastructure network were far from the idea of fast modernity pursued in the 1964 Plan, and were set to define an alternative scenario to that linked to the use of the car. The two existing and unused railway lines were indicated as connections to be recovered to set up a light rail system, a way of crossing the territory more appropriate to the new centrality of the environmental system.

The drawings of the 1994 Plan, articulated from planning up to detailed scales (1:20 – ½”:1’ approx.), the urban diagrams that form the background for the Detailed Plans program (dedicated to the transformation or realization of certain old and new architectures), the reasoning developed on the territory and on its enhancement, the tools designed to act on some transformations: they are all materials that today allow us to reflect on the directions of contemporary design and urbanism. The 1994 Plan is a document that largely follows many of the problems of this time and proposes solutions that are still feasible. Starting from this document, it is possible to reactivate a research track on the architecture of the countryside, that in Italy disappeared in the 1950s (shortly after the construction of the La Martella district of Ludovico Quaroni in Matera), and expand an operational reasoning on how to re-inhabit the internal and empty territories of the European continent.

The Matteotti Village in GDC’s Communication Strategies

The talk by Alberto Franchini, Research Fellow at the Academy of Architecture, Universita’ della Svizzera Italiana, at Mendrisio (Switzerland), focused on De Carlo’s rhetorical and communicative skills in the story of the Matteotti Village (1969-75) in Terni (Italy). It was thanks also to the careful selection of words and images by its designer that this residential complex quickly became an “emblematic case of participation.” The close comparison between De Carlo’s story and the real events of the project, brings out, in addition to the obvious gap between theory and praxis, some evident incongruity. Some hypotheses have been provided to reflect on the distance between Matteotti Village’s media value and its actual impact on architectural practice.

The Matteotti Village (1969-75) represented a breaking point in De Carlo’s career and developed some of the reasoning used in the organisation of the controversial XIV Milan Triennale of 1968, dedicated to the theme of the “Big Number.” At the time he was entrusted with the assignment for the drawing-up of the housing intervention intended for the employees of the Terni steelworks, the architect was barely 50 years old and at the height of international success and affirmation.

De Carlo worked in Terni, trying to educate the workers’ commission, to make them more aware of their own needs and to allow them to make a competent choice to determine the space that they would have wanted to live in. The preliminary project was discussed by the designer with the top management, after which interviews with a sample of potential users were organized with sociologist Domenico De Masi. Given the limited usefulness of these interviews, it was decided to set up an exhibition showing four significant examples of collective housing with the help of Cesare De Seta for the graphic elaborations and detailed explanations. In this way, future inhabitants were “educated” and on the basis of this knowledge, debates were opened, from which further questions emerged. On the one hand, De Carlo’s narrative was addressed to Terni employees and potential users directly involved in the process through the organisation of two exhibitions and the drafting of two issues of the corporate newspaper; on the other hand, it was open to the world of architecture.

The 421 issue of Casabella (1977), the first under the new editorship by Tomás Maldonado, caused a real disconnection between the actual events and the narration of events that followed its own path. Although this issue was dedicated almost exclusively to the Matteotti Village and collected the contributions of many of the protagonists of this realisation, it was the photographs by Gabriele Basilico, especially of interiors, that highlighted the counterpoint between the uniform quality of the architecture and the diversity of environments inhabited by the workers.

The Relationship Between City and University in GDC’s Teaching at the IUAV

Lorenzo Mingardi, Research Fellow and Lecturer at the University of Florence, considered the teaching of De Carlo and how the idea of the city and its connections with the university were addressed in his activity. For De Carlo, teaching, exercised throughout his life (first at IUAV, then in Genoa and then, in parallel, at the ILAUD), was one of his most important fields of activity. His was not solely an ex-cathedra type of teaching, but a continuous laboratory, sustained by a strong ethical charge, which he was able to convey to his students. His teaching had firm and rigorous method references, but it hardly ever reached absolutes, and provided for continuous critical checks during the design process. The same checks that, as an architect, he also sought in his work.

De Carlo began to teach at a very young age. When he taught at the Scuola Umanitaria di Milano in 1948, he was not even 30 years old. A few years after his second degree from the IUAV (in architecture, after a first degree in structural engineering from the Politecnico in Milan), De Carlo began to collaborate as a volunteer assistant with Giuseppe Samonà, then Professor and Dean at the IUAV. From the academic year 1956-57, he was requested to take on the teaching of Elements of Architecture and Measure Drawings of Monuments. Despite having obtained his teaching qualification in architectural composition, he directed his academic career towards Urban Design very early on. In the academic year 1964-65 (the decisive years for the Master Plan of Urbino), he was in charge of teaching urban design; from 1966 it became a permanent position until 1969, when he became an Professor of Urban Design. De Carlo reached the peak of his academic career precisely in the years in which his pedagogy started to diverge more and more from that one pursued by IUAV after Samonà’s departure. Thus began a journey that brought him in about ten years to abandon IUAV to go and teach architectural design in Genoa in 1983.

The thread that bound all of De Carlo’s university activities was his being first and foremost an educator. De Carlo was a teacher who worked to stimulate the power of observation. Students must be educated in their own city, in the active awareness of the city in which they reside. Because it is the students who will have to build the new cities and therefore, tout court, the new society. Each of De Carlo’s teaching activities, mostly at IUAV, but not only, was aimed at achieving this goal: to empower students to create a better world.

In this way of understanding teaching, we could call him a “new Patrick Geddes.” Geddes’ range of skills was very broad: professor, botanist, scientist, educator, pedagogue; for him, teaching had to be passed on through experience, and only later through books.

De Carlo also educated his students through built architectures: he loaded all his architectural or urban interventions with strong pedagogical contents. In this way the project is not only entrusted with the task of solving a problem, but also to educate both users and students about the operation that is intended to be carried out.

The Current State of Research on GDC

Manuel Orazi, Press Agent of Quodlibet publishing house, discussed De Carlo’s posthumous editorial success. The Genoese architect had always had a close link with the publishing world, also involving his family in this passion. In the post-WWII period, he and his wife, Giuliana Baracco, translator and magazine editor, lived in a duplex apartment together with the family of Elio Vittorini, a writer and public intellectual who at that time worked for Einaudi publishing house.

The long summer holidays spent in Bocca di Magra (south of Genoa) were animated by meetings with great intellectuals all united by their involvement with editorial work: Vittorio Sereni, Italo Calvino, Cesare Pavese, Franco Fortini, Giulio Einaudi himself (the owner of the publishing house) and many others. While in the early ‘60s, academic teaching brought De Carlo closer to the newly-founded publisher Marsilio of planner and intellectual Paolo Ceccarelli, among others, at the turn of the ‘70s the experience of the De Carlos continued with Il Saggiatore publisher in Milan thanks to the imprint “Forma e struttura urbana” (Form and Urban Structure) which featured many unpublished authors (almost always translated by Giuliana), and later with the magazine Spazio e Società / Space & Society, which closed in 2001 after having changed various publishers (including The MIT Press).

After his death in 2005, books by and on De Carlo began to circulate, parallel to new studies on his work, until the flourishing of initiatives that culminate today with the centenary of his birth. In any case, De Carlo’s posthumous success is unquestionable. Also abroad, thanks to the work of historians such as John McKean, Tom Avermaete, Jeremy Till, Adam Wood and others, monographic books, essays, magazine articles and even documentary films have been published every year from 2004 till present day. There are also numerous reprints of De Carlo’s books, some in a new critical edition – that is, with a choice of essays not written by the author, updated by interpretative essays, which distinguishes them from mere archival operations.

In general, the editorial production on and by De Carlo reflects his erratic and transversal trajectory, i.e. not only and not so many large Milanese publishing houses, but also publishers from many parts of Italy, often the same ones that have witnessed his activity during his long career, such as in the Marche and Sicily. In short, the transversality of De Carlian thought, which will emerge even more powerfully with the publication of his unpublished diaries, is a consequence of his being a maverick (also for personality traits) at the helm of two organizations unfettered by statute, such as ILAUD and Spazio e Società. In short, his nature reflects his geographic itinerary without a real centre, although Milan has been more like a centre of gravity among other equally significant cities (Venice, Urbino, Genoa), albeit with thoughts always projected towards a more distant and intimate horizon: Greece and its archipelago full of Le Corbuserian memories and vernacular outdoor spaces, travelling every summer to a new place and in a different way, in the footsteps of the ghosts of the WWII who right there had irreparably marked his young, restless, libertarian, shadowy personality.

Blue Moon at the Lido Between Awareness and Protection

Francesco Trovò, Superintendent for Archeology, Fine Arts and Landscape, for the City of Venice and its Lagoon, delivered a paper on Blue Moon (Lido di Venezia, 2002): a work on which critics have repeatedly expressed a unanimous reserved judgement. The critical findings were fuelled, as also in case of the gateways to San Marino, particularly by the unexpected linguistic innovations introduced by De Carlo and despite those architectures being the expression of a proven design methodology, founded on the reading and morphology of the site. Starting from these considerations, the analysis of the building was conducted starting from a reading of the photographic documents that described the permanence on that site of a collective history linked to the relationship with the sea and the theme of bathing as a collective activity. The Lido is not only a physical place, but above all a literary place, and De Carlo proved to be particularly sensitive to its fascination. Seaside architecture is made up of ephemeral yet evocative images and Blue Moon remains faithful to this model, in which De Carlo tried to capture the visions of movie director Luchino Visconti, the colours of Oskar Kokoschka and Canaletto, the prose of Lord Byron and Henry James.

The regulatory layout of the complex highlights De Carlo’s approach aimed at combining the area access system, the garden towards the road, the volumes intended for the various accommodation functions, the curve of the shore and the momentum in the same gesture of the pier towards the sea. The articulated complex of the beach resort has arcades on the ground floor with windows protected by wooden slats to filter out the harsh summer light. The upper terraces are dominated by the presence of an ephemeral metallic dome from which soars like fireworks a mast that supports a crow’s nest, elements of a maritime landscape that transform the buildings into as many vessels stranded on the beach. Finally, towards the beach, on the terrace curved towards the sea, four domes rest to form a quincunx, reminiscent of the ancient Byzantine domes belonging to the first St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. From the terraces, a slender metal pier, originally conceived as a walkway that went into the sea, leads guests as far as the shoreline, stopping on the line that separates land from sea.

The whole complex is now in a state of regrettable abandonment and the Superintendent Office has been dealing with its preservation for years. An architectural work whose execution dates back to a period of less than seventy years cannot be subject tout court to preservation and the Superintendent has only been able to preserve the building directly thanks to the value it represents for the landscape in which it is inserted.

In particular, the metal walkway – which has since been dismantled because of corrosion – if it were not rebuilt, would represent a serious loss to the delicate landscape of the coast.

As observed by the discussant Chiara Ferro of the Superintendent Office, these events highlight the contradictions of a modernity that too often demands the demolition of historic buildings without serious reflection, demonstrating however its impotence when, due to a change of ownership or function, it is forced to recognize the fragility of its own existence.

CONCLUSIONS

At the end of the two symposium sessions, a round table was opened, whose participants comprised: engineer Giuseppe Carniello, who had collaborated with GDC on the drafting of some projects, including a futuristic parking lot for the city of Trento; Francesco Ceccarelli, who remembered the house in Bologna designed by GDC in which he grew up; Alberto Cecchetto, who reflected on the reasons behind the project, the realization and the life that flows today in the housing district built in Mazzorbo, in the Venice Lagoon; Leonardo Ciacci, who addressed the methods and experience of GDC as professor at IUAV; Chiara Ferro, who highlighted problems and prospects for the protection of modern works today in Venice; and finally, Franco Mancuso, who rendered the picture of a complex personality, of a multi-faceted and manifold activity, underlining all the connections between his work and current issues.

In closing, the stages of the project for the celebrations of the centenary of De Carlo’s birth scheduled for 2020 were illustrated. During the year, it is planned the organization of a meeting for dialogue and discussion between those architects and architectural critics who saw De Carlo as a crucial point of reference for the architectural debate in Italy in the late twentieth century. Finally, it is planned the promotion of a more assiduous protection of De Carlo’s architecture through a photographic campaign with the aim of documenting the state of conservation of his works carried out in the Venice Lagoon and in the Province of Venice: the Mazzorbo neighbourhood and gym, Blue Moon at the Lido and the hospital at Mirano. This is an activity that it is intended to take place alongside that one of enhancing De Carlo’s legacy present in the IUAV Archivio Progetti.

A final note by the authors: new research is being developed, focusing on the architectural exhibitions curated by De Carlo, on his projects for private houses and on the reconstruction of his intellectual biography through the testimonies documented in his correspondence.

Franco Buncuga, Conversazioni su architettura e libertà (Milan: Elèuthera, 2014), 201.

Giancarlo De Carlo, Urbino. The History of a City and Plans for Its Development, trans. Lotetta Schaeffer Guarda (Cambridge MA, USA: 1970).

Urbanistica 102 (1994).

Figs. 2-9: photos by © Ferro/Pilot IUAV Photographic Laboratory, 2020.

Sara Marini, architect, PhD, is a Full Professor of Architectural and Urban Design at the Università IUAV in Venice. Since 2020 she is the coordinator of the IUAV research unit for PRIN national research “Sylva”. Since 2019 she has been the Editor of Vesper. Journal of Architecture, Arts & Theory, Department of Architecture and Art, IUAV. In 2018 she exhibited “Casa nera” in the Italian Pavilion at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale. Recent publications include Venice. 2nd Document (ed. with Alberto Bertagna, 2017); Le concert. Pink Floyd à Venise (with Samuel Lorrain, Léa-Catherine Szacka, 2017); Recycled Theory. Illustrated Dictionary (ed. with Giovanni Corbellini, 2016). E-mail: marini@iuav.it

Marko Pogacnik is a Full Professor of History of Architecture at the Università IUAV in Venice. Previously, he taught as a Visiting Professor at various universities in Germany and Austria. Invited by the National Museum of Contemporary Art of Seoul, he served as jury member for the competition for the new MoCA Seoul (2010). In 2014, he curated the exhibition Details: architecture seen in section, for the Venice Architecture Biennale.

He curated the exhibition Adolf Loos und Wien, in Vienna (2011-12) and Venice (2016). He published extensively on major protagonists of the history of architecture, such as Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Adolf Loos, Carlo Scarpa, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier. E-mail: pogacnik@iuav.it